Sidon or Saida is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. Tyre to the south and Lebanese capital Beirut to the north are both about 40 kilometres away. Sidon has a population of about 80,000 within city limits, while its metropolitan area has more than a quarter-million inhabitants.

Myra was a Lycian, then ancient Greek, then Greco-Roman, then Byzantine Greek, then Ottoman town in Lycia, which became the small Turkish town of Kale, renamed Demre in 2005, in the present-day Antalya Province of Turkey. It was founded on the river Myros, in the fertile alluvial plain between Alaca Dağ, the Massikytos range and the Aegean Sea.

Xanthos or Xanthus, also referred to by scholars as Arna, its Lycian name, was an ancient city near the present-day village of Kınık, in Antalya Province, Turkey. The ruins are located on a hill on the left bank of the River Xanthos. The number and quality of the surviving tombs at Xanthos are a notable feature of the site, which, together with nearby Letoon, was declared to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988.

A sarcophagus is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word sarcophagus comes from the Greek σάρξsarx meaning "flesh", and φαγεῖνphagein meaning "to eat"; hence sarcophagus means "flesh-eating", from the phrase lithos sarkophagos, "flesh-eating stone". The word also came to refer to a particular kind of limestone that was thought to rapidly facilitate the decomposition of the flesh of corpses contained within it due to the chemical properties of the limestone itself.

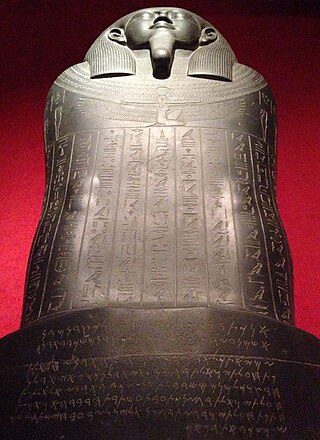

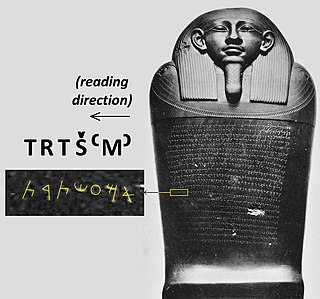

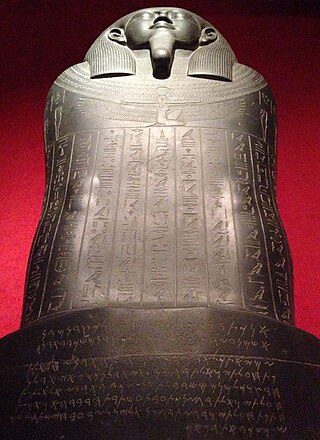

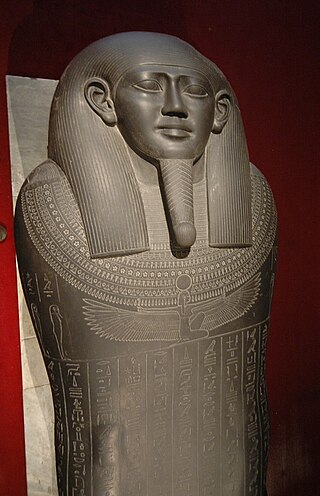

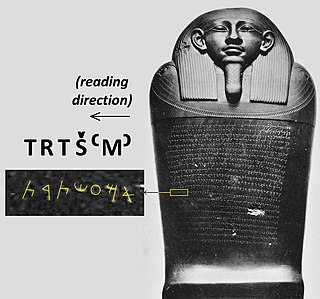

The sarcophagus ofEshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis southeast of the city of Sidon, in modern-day Lebanon, that contained the body of Eshmunazar II, Phoenician King of Sidon. One of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's father King Tabnit and to a woman, possibly Eshmunazar's mother Queen Amoashtart, it was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head. The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

The Alexander Sarcophagus is a late 4th century BC Hellenistic stone sarcophagus from the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon. It is adorned with high relief carvings of Alexander the Great and scrolling historical and mythological narratives. The work is considered to be remarkably well preserved, and has been used as an exemplar for its retention of polychromy. It is currently in the holdings of the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums are a group of three archaeological museums located in the Eminönü quarter of Istanbul, Turkey, near Gülhane Park and Topkapı Palace. These museums house over one million objects from nearly all periods and civilizations in world history.

The royal necropolis ofAyaa was a group of two hypogea housing a total of 21 sarcophagi of kings and nobles of the city of Sidon, a coastal city in Lebanon, and a prominent Phoenician city-state. The sarcophagi were highly diverse in style, ranging across Egyptian, Greek, Lycian and Phoenician styles. The Phoenicians exhibited diverse mortuary practices that included inhumation and cremation. While written records about their beliefs in the afterlife are scarce, archaeological evidence suggests they believed in an afterlife known as the "House of Eternity." Burial sites in Iron Age Phoenicia, like the Ayaa necropolis, were typically located outside settlements, and featured various tomb types and burial practices.

Antiphellus or Antiphellos, known originally as Habesos, was an ancient coastal city in Lycia. The earliest occurrence of its Greek name is on a 4th-century-BCE inscription. Initially settled by the Lycians, the city was occupied by the Persians during the 6th century BCE. It rose in importance under the Greeks, when it served as the port of the nearby inland city of Phellus, but once Phellus started to decline in importance, Antiphellus became the region's largest city, with the ability to mint its own coins. During the Roman period, Antiphellus received funds from the civic benefactor Opramoas of Rhodiapolis that may have been used to help rebuild the city following the earthquake that devastated the region in 141.

The Tomb of Payava is a Lycian tall rectangular free-standing barrel-vaulted stone sarcophagus, and one of the most famous tombs of Xanthos. It was built in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, for Payava, who was probably the ruler of Xanthos, Lycia at the time, in around 360 BC. The tomb was discovered in 1838 and brought to England in 1844 by the explorer Sir Charles Fellows. He described it as a 'Gothic-formed Horse Tomb'. According to Melanie Michailidis, though bearing a "Greek appearance", the Tomb of Payava, the Harpy Tomb and the Nereid Monument were built according to the main Zoroastrian criteria "by being composed of thick stone, raised on plinths off the ground, and having single windowless chambers".

The Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approximately 480–470 BC, the chamber topped a tall pillar and was decorated with marble panels carved in bas-relief. The tomb was built for an Iranian prince or governor of Xanthus, perhaps Kybernis.

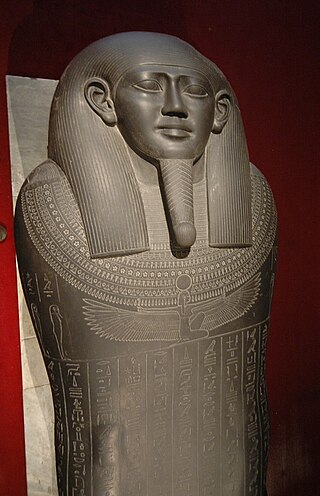

The Tabnit sarcophagus is the sarcophagus of the Phoenician King of Sidon Tabnit, the father of King Eshmunazar II. It is decorated with two separate and unrelated inscriptions – one in Egyptian hieroglyphs and one in the Phoenician alphabet. The latter contains a curse for those who open the tomb, promising impotency and loss of an afterlife.

Tabnit was the Phoenician King of Sidon c. 549–539 BC. He was the father of King Eshmunazar II.

Xanthos, also called Xanthus, was a chief city state of the Lycians, an indigenous people of southwestern Anatolia. Many of the tombs at Xanthos are pillar tombs, formed of a stone burial chamber on top of a large stone pillar. The body would be placed in the top of the stone structure, elevating it above the landscape. The tombs are for men who ruled in a Lycian dynasty from the mid-6th century to the mid-4th century BCE and help to show the continuity of their power in the region. Not only do the tombs serve as a form of monumentalization to preserve the memory of the rulers, but they also reveal the adoption of Greek style of decoration.

The Ship Sarcophagus, also known as the Sarcophagus au Navire, is a Roman era sarcophagus found by Georges Contenau in 1913 in Magharet Abloun, a necropolis containing the remains of Phoenician kings and notables in the south of Sidon in modern-day Lebanon. The sarcophagus has been dated to the 2nd century CE.

Greco-Persian art, also Graeco-Persian art or Anatolian-Persian is an artistic synthesis between Ancient Greek art and Achaemenid Persian art, which can mainly be seen in the archaeological finds of ancient Anatolia in present-day Turkey. It is part of the evidence of "the presence of Persians in the region". It has been defined as "a peculiar blend of Hellenistic and Achaemenid, or pseudo-Achaemenid, styles" in the Anatolian peninsula under Achaemenid rule.

Amoashtart was a Phoenician queen of Sidon during the Persian period. She was the daughter of Eshmunazar I, and the wife of her brother, Tabnit. When Tabnit died, Amoashtart became co-regent to her then-infant son, Eshmunazar II, but after the boy died "in his fourteenth year", she was succeeded by her nephew Bodashtart, possibly in a palace coup. Modern historians have characterized her as an "energetic, responsible [woman], and endowed with immense political acumen, [who] exercised royal functions for many years".

The Sarcophagus of the mourning women is a Hellenistic sarcophagus found in 1887 by the Ottoman archaeologist Osman Hamdi Bey, in the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon, in the same burial chamber as the Alexander sarcophagus.

The Sarcophagus of the Satrap is an ancient Hellenistic marble funerary monument discovered at the Ayaa Necropolis in Sidon, present-day Lebanon, and is believed to originate from the Achaemenid Persian Empire period. The reliefs are believed to depict a Persian Satrap, whose body is assumed to have inhabited the tomb.

Keeper of the Mausoleum also known as Old man in front of children’s graves or Old man in front of children's tombs is a 1903 painting by Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910).