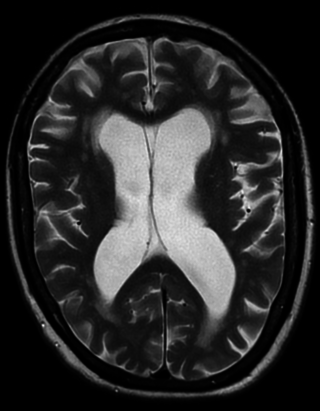

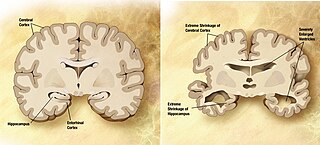

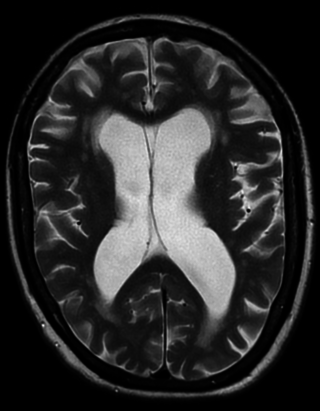

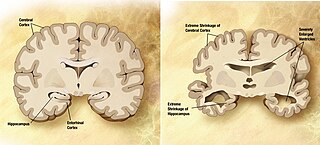

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that affects a person's ability to perform everyday activities. This typically involves problems with memory, thinking, behavior, and motor control. Aside from memory impairment and a disruption in thought patterns, the most common symptoms of dementia include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and decreased motivation. The symptoms may be described as occurring in a continuum over several stages. Dementia ultimately has a significant effect on the individual, their caregivers, and their social relationships in general. A diagnosis of dementia requires the observation of a change from a person's usual mental functioning and a greater cognitive decline than might be caused by the normal aging process.

Vascular dementia is dementia caused by a series of strokes. Restricted blood flow due to strokes reduces oxygen and glucose delivery to the brain, causing cell injury and neurological deficits in the affected region. Subtypes of vascular dementia include subcortical vascular dementia, multi-infarct dementia, stroke-related dementia, and mixed dementia.

The Mediterranean diet is a concept first invented in 1975 by the American biologist Ancel Keys and chemist Margaret Keys. The diet took inspiration from the supposed eating habits and traditional food typical of Cyprus, much of the rest of Greece, and southern Italy, and formulated in the early 1960s. It is distinct from Mediterranean cuisine, which covers the actual cuisines of the Mediterranean countries, and from the Atlantic diet of northwestern Spain and Portugal. While inspired by a specific time and place, the "Mediterranean diet" was later refined based on the results of multiple scientific studies.

Cognitive disorders (CDs), also known as neurocognitive disorders (NCDs), are a category of mental health disorders that primarily affect cognitive abilities including learning, memory, perception, and problem-solving. Neurocognitive disorders include delirium, mild neurocognitive disorders, and major neurocognitive disorder. They are defined by deficits in cognitive ability that are acquired, typically represent decline, and may have an underlying brain pathology. The DSM-5 defines six key domains of cognitive function: executive function, learning and memory, perceptual-motor function, language, complex attention, and social cognition.

Cognitive reserve is the mind's and brain's resistance to damage of the brain. The mind's resilience is evaluated behaviorally, whereas the neuropathological damage is evaluated histologically, although damage may be estimated using blood-based markers and imaging methods. There are two models that can be used when exploring the concept of "reserve": brain reserve and cognitive reserve. These terms, albeit often used interchangeably in the literature, provide a useful way of discussing the models. Using a computer analogy, brain reserve can be seen as hardware and cognitive reserve as software. All these factors are currently believed to contribute to global reserve. Cognitive reserve is commonly used to refer to both brain and cognitive reserves in the literature.

A cognitive intervention is a form of psychological intervention, a technique and therapy practised in counselling. It describes a myriad of approaches to therapy that focus on addressing psychological distress at a cognitive level. It is also associated with cognitive therapy, which focuses on the thought process and the manner by which emotions have bearing on the cognitive processes and structures. The cognitive intervention forces behavioral change. Counselors adopt different technique level to suit the characteristic of the client. For instance, when counseling adolescents, a more advanced strategy is adopted than the intervention used in children. Before the intervention, an initial cognitive assessment is also conducted to cover the concerns of the cognitive approach, which cover the whole range of human expression - thought, feeling, behavior, and environmental triggers.

Cognitive impairment is an inclusive term to describe any characteristic that acts as a barrier to the cognition process or different areas of cognition. Cognition, also known as cognitive function, refers to the mental processes of how a person gains knowledge, uses existing knowledge, and understands things that are happening around them using their thoughts and senses. A cognitive impairment can be in different domains or aspects of a person's cognitive function including memory, attention span, planning, reasoning, decision-making, language, executive functioning, and visuospatial functioning. The term cognitive impairment covers many different diseases and conditions and may also be symptom or manifestation of a different underlying condition. Examples include impairments in overall intelligence, specific and restricted impairments in cognitive abilities, neuropsychological impairments, or it may describe drug-induced impairment in cognition and memory. Cognitive impairments may be short-term, progressive or permanent.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a neurocognitive disorder which involves cognitive impairments beyond those expected based on an individual's age and education but which are not significant enough to interfere with instrumental activities of daily living. MCI may occur as a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia, especially Alzheimer's disease. It includes both memory and non-memory impairments. The cause of the disorder remains unclear, as well as both its prevention and treatment, with some 50 percent of people diagnosed with it going on to develop Alzheimer's disease within five years. The diagnosis can also serve as an early indicator for other types of dementia, although MCI may remain stable or even remit.

The prevention of dementia involves reducing the number of risk factors for the development of dementia, and is a global health priority needing a global response. Initiatives include the establishment of the International Research Network on Dementia Prevention (IRNDP) which aims to link researchers in this field globally, and the establishment of the Global Dementia Observatory a web-based data knowledge and exchange platform, which will collate and disseminate key dementia data from members states. Although there is no cure for dementia, it is well established that modifiable risk factors influence both the likelihood of developing dementia and the age at which it is developed. Dementia can be prevented by reducing the risk factors for vascular disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, smoking, physical inactivity and depression. A study concluded that more than a third of dementia cases are theoretically preventable. Among older adults both an unfavorable lifestyle and high genetic risk are independently associated with higher dementia risk. A favorable lifestyle is associated with a lower dementia risk, regardless of genetic risk. In 2020, a study identified 12 modifiable lifestyle factors, and the early treatment of acquired hearing loss was estimated as the most significant of these factors, potentially preventing up to 9% of dementia cases.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens, and is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems with language, disorientation, mood swings, loss of motivation, self-neglect, and behavioral issues. As a person's condition declines, they often withdraw from family and society. Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death. Although the speed of progression can vary, the average life expectancy following diagnosis is three to twelve years.

Souvenaid is a dietary supplement in the form of a thick, yogurt-like drink that is marketed as helping people with Alzheimer's disease. It contains a mixture of water, food coloring, artificial flavors, sugar, docosahexaenoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, phospholipids, choline, uridine monophosphate, vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol equivalents), selenium, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, and folic acid; this mixture is branded as Fortasyn Connect.

Solanezumab is a monoclonal antibody being investigated by Eli Lilly as a neuroprotector for patients with Alzheimer's disease. The drug originally attracted extensive media coverage proclaiming it a breakthrough, but it has failed to show promise in Phase III trials.

Type 3 diabetes is a proposed pathological linkage between Alzheimer's disease and certain features of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Specifically, the term refers to a set of common biochemical and metabolic features seen in the brain in Alzheimer's disease, and in other tissues in diabetes; it may thus be considered a "brain-specific type of diabetes." It was recognized at least as early as 2005 that some features of brain function in Alzheimer's disease mimic those that underlie diabetes. However, the concept of type 3 diabetes is controversial, and as of 2021 it was not a widely or generally recognized diagnosis.

Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) is a multisite study that aims to improve clinical trials for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD). This cooperative study combines expertise and funding from the private and public sector to study subjects with AD, as well as those who may develop AD and controls with no signs of cognitive impairment. Researchers at 63 sites in the US and Canada track the progression of AD in the human brain with neuroimaging, biochemical, and genetic biological markers. This knowledge helps to find better clinical trials for the prevention and treatment of AD. ADNI has made a global impact, firstly by developing a set of standardized protocols to allow the comparison of results from multiple centers, and secondly by its data-sharing policy which makes available all at the data without embargo to qualified researchers worldwide. To date, over 1000 scientific publications have used ADNI data. A number of other initiatives related to AD and other diseases have been designed and implemented using ADNI as a model. ADNI has been running since 2004 and is currently funded until 2021.

Postmenopausal confusion, also commonly referred to as postmenopausal brain fog, is a group of symptoms of menopause in which women report problems with cognition at a higher frequency during postmenopause than before.

Although there are many physiological and psychological gender differences in humans, memory, in general, is fairly stable across the sexes. By studying the specific instances in which males and females demonstrate differences in memory, we are able to further understand the brain structures and functions associated with memory.

Research into food preferences in older adults and seniors considers how people's dietary experiences change with ageing, and helps people understand how taste, nutrition, and food choices can change throughout one's lifetime, particularly when people approach the age of 70 or beyond. Influencing variables can include: social and cultural environment, gender and/or personal habits, and also physical and mental health. Scientific studies have been performed to explain why people like or dislike certain foods and what factors may affect these preferences.

The Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center (RADC) is an independent research center located in the Medical College of Rush University Medical Center. The Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center is one of the Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers in the U.S. designated and funded by the National Institute on Aging.

Julia Louise Bienias is an American biostatistician known for her highly-cited publications on Alzheimer's disease.

Martha Clare Morris was an American nutritional epidemiologist who studied the link between diet and Alzheimer's disease. She led a team of researchers at the Rush University Medical Center to develop the MIND diet.