Manuel Mendive Hoyos (born 1944) is an Afro-Cuban artist.

Manuel Mendive Hoyos (born 1944) is an Afro-Cuban artist.

Mendive was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1944. His family practiced La Regla de Ocha, or Santería. A mulatto, he cherishes his Yoruba roots from the West coast of Africa. [1] In 1963, he graduated from the San Alejandro Academy of Plastic Arts, Havana.

He has received numerous awards for his art within exhibitions in Cuba and in Europe. Since the beginning of his artistic career, he has participated in many group and solo art exhibits. His first one-man show was held at the Center of Art in Havana, in 1964. [2] In 1968, he was awarded with the Adam Montparnasse prize for his painting exhibit at the Salon de Mai, in Paris, and third prize at the Salón Nacional de Artes Plásticas, in Havana. [2] Additional noteworthy awards Mendive has received include the Alejo Carpentier Medal from the Consejo de Estado of the Republic of Cuba, in 1988, and the Chevalier des Arts et Lettres from the Minister of Culture and Francophony of the French Republic, in 1994. [3] Today, his art resides in museums and galleries all over the world which include Cuba, Russia, Somalia, Benin, Congo, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Jamaica, and the United States.

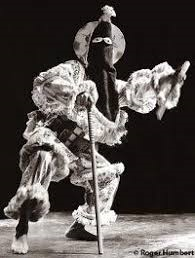

Mendive's work incorporates several art mediums and genres. His art consists of drawing, painting, body painting, wood carving, sculpture, and performance that integrates loosely choreographed dance with rhythmic music. At times, the availability of art materials was rather scarce due to the harsh economic climate of the island. As a result, he relied on his creativity and resourcefulness to obtain various mediums, commonly found in nature. Much of his work consists of paint and wood, which he combines with other interesting elements, such as, human hair, sand, feathers, and glass that convey a primitive quality. [4] He not only paints with oils and pastels on canvases, but he paints on masks and posters. Mendive is also famous for his representation of saints and Lukumi gods through his use of carved, burned, and painted wood that he made during the 1960s. [5]

Mendive's art is strongly influenced by the Santería religion. In fact, Santería permeates every form of his art from body painting to events performed in public spaces. [1]

In the 1960s and 1970s, his most significant works were created, and they depict a primitive display of Yoruba mythology with his use of raw materials that resemble altars. A prime example that his style is primitive and mythological is reflected in his art piece "Voodoo Altar" displayed at the Museo Nacional de Guanabacoa, in Cuba. Some of the materials Mendive's used to create "Voodoo Altar" include twigs, feathers, and hair. According to the Cuban art critique Gerardo Mosquera, his art does not contain ceremonial function, but possesses a sense of 'living mythological thought' and utilizes Afro-Cuban imagery to study the questions of contemporary life. [6] His mythological and religious themes are evident in his 1967 painting "Oya", which is the Yoruba goddess of storms. Oya is associated with the passage from life into death and Mendive had a fascination with death during his 'dark period' in the late 1960s. [7] An example of his primitive, Afro-Cuban imagery is seen in his 1976 painted wood carving, "Slave Ship", which epitomizes the onset of the struggles in modern-day life. His art is minimalistic, yet it is thought provoking.

In the 1970s, he continued to promote Afro-Cuban culture through his colorful art by referencing the Middle Passage, colonialism, Cuban history, and Yoruba history. [8] His art is a mixture of African and European styles. He uses this culmination of African and European techniques and traditions to showcase his Afro-Cuban style to the Western world. Mendive displays a narration in much of his art and performances. This is evident in his 1968 painting of Che Guevara, which offers a visual narrative to the Western world about Che Guevara's positive influence in Cuba. Gerardo Mosquera meditatively remarks on Mendive's art, "the black person tends to be integrated with few contradictions into a new entity: the Cuban nation." [9] Mendive is successful at producing art that combines Afro-Cuban culture with international themes to make an ideological statement about social issues in Cuba. In addition, his art illustrates the influences that came from Africa and Europe in Cuba.

From the mid-1960s to 2010, much of his work includes paintings and drawings that portray spirits and Orisha saints through the use of a wide array of colors and smooth, flowing shapes. The primary theme in his art is his recognition that African religion and African culture have shaped Cuban national identity and culture. Gerardo Mosquera praises him for his art because Mendive acknowledges the rich tapestry of African contributions to the Cuban culture. [9]

Mendive recently exhibited at the N'Namdi Center for Contemporary Art in Detroit. [10]

In 1982, Mendive made his first trip to West Africa and traveled throughout the region for a year gaining new insight into his Yoruba roots. [11] He drew energy from spending time in Africa and became inspired on a whole new level. After his return to Cuba, his art portrayed images connected with the natural environment, such as, his 1984 painting "Viento a Fete". [11] Mendive's work was exhibited at the "Ouidah '92" festival, which celebrated Vodun art from Benin and the African Diaspora in Ouidah, Benin in February 1993. [12] An example of his belief that African religion and culture are linked with the natural world is captured through his 1997 painting "Olofi, the Spirits, Man and Nature". In addition, his performances exemplify his heightened passion of the African culture. His interest in the culture was made apparent in his 1986 performance "La vida", in which he painted the bodies and faces of the dancers with flowing lines that symbolize spirits. [11]

Vodun is a religion practiced by the Aja, Ewe, and Fon peoples of Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Ogun or Ogoun is a spirit that appears in several African religions. He attempted to seize the throne after the demise of Obatala, who reigned twice, before and after Oduduwa, but was ousted by Obamakin and sent on an exile – an event that serves as the core of the Olojo Festival. Ogun is a warrior and a powerful spirit of metal work, as well as of rum and rum-making. He is also known as the "god of iron" and is present in Yoruba religion, Haitian Vodou, and West African Vodun.

Wifredo Óscar de la Concepción Lam y Castilla, better known as Wifredo Lam, was a Cuban artist who sought to portray and revive the enduring Afro-Cuban spirit and culture. Inspired by and in contact with some of the most renowned artists of the 20th century, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Lam melded his influences and created a unique style, which was ultimately characterized by the prominence of hybrid figures. This distinctive visual style of his also influences many artists. Though he was predominantly a painter, he also worked with sculpture, ceramics and printmaking in his later life.

Cowrie-shell divination refers to several distinct forms of divination using cowrie shells that are part of the rituals and religious beliefs of certain religions. Though best-documented in West Africa as well as in Afro-American religions, such as Santería, Candomblé, and Umbanda, cowrie-shell divination has also been recorded in India, East Africa, and other regions.

The Yoruba religion, or Isese, comprises the traditional religious and spiritual concepts and practice of the Yoruba people. Its homeland is in present-day Southwestern Nigeria, which comprises the majority of Oyo, Ogun, Osun, Ondo, Ekiti, Kwara and Lagos States, as well as parts of Kogi state and the adjoining parts of Benin and Togo, commonly known as Yorubaland. It shares some parallels with the Vodun practiced by the neighboring Fon and Ewe peoples to the west and to the religion of the Edo people and Igala people to the east. Yoruba religion is the basis for a number of religions in the New World, notably Santería, Umbanda, Trinidad Orisha, and Candomblé. Yoruba religious beliefs are part of Itàn (history), the total complex of songs, histories, stories, and other cultural concepts which make up the Yoruba society.

Afro-Cubans or Black Cubans are Cubans of sub-Saharan African ancestry. The term Afro-Cuban can also refer to historical or cultural elements in Cuba thought to emanate from this community and the combining of native African and other cultural elements found in Cuban society such as race, religion, music, language, the arts and class culture.

Abakuá, also sometimes known as Ñañiguismo, is an Afro-Cuban men's initiatory fraternity or secret society, which originated from fraternal associations in the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon.

Cuban art is an exceptionally diverse cultural blend of African, South American, European, and North American elements, reflecting the diverse demographic makeup of the island. Cuban artists embraced European modernism, and the early part of the 20th century saw a growth in Cuban avant-garde movements, which were characterized by the mixing of modern artistic genres. Some of the more celebrated 20th-century Cuban artists include Amelia Peláez (1896–1968), best known for a series of mural projects, and painter Wifredo Lam, who created a highly personal version of modern primitivism. The Cuban-born painter Federico Beltran Masses (1885–1949), was renowned as a colorist whose seductive portrayals of women sometimes made overt references to the tropical settings of his childhood.

Calixte Dakpogan is a Beninese sculptor known for his installations as well as his masks made out of diverse and original found materials. A native of Pahou, he currently lives and works in Porto Novo. Much of his work is inspired by his Voudon heritage.

Lázaro Ros was an Afro-Cuban singer. His music borrowed much from Africa, as he performed music of the Lucumí culture, of the Yoruba people from modern-day Nigeria, and of the Arará culture of the Dahomeyan people from modern-day Benin. Ros was largely self-taught, and first learned to sing by learning the chants associated with Santería, a religion based in the Lucumí and Arará cultures.

Juan Boza Sánchez or Juan Stopper Sanchez was a gay Afro-Cuban-American artist specializing at painting, drawing, engraving, installation and graphic design.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons is a Cuban-born artist based in Nashville, Tennessee. Campos-Pons works primarily in photography, performance, audiovisual media, and sculpture. She is considered a "key figure" among Cuban artists who found their voice in a post-revolutionary Cuba. Her art deals with themes of Cuban culture, gender and sexuality, multicultural identity as well as interracial family (Cuban-American), and religion/spirituality.

Grupo Antillano was a Cuban artistic group was formed by 16 artists, between 1975 and 1985, in Havana, Cuba.

Gerardo Mosquera is a freelance curator, critic, art historian, and writer based in Havana, Cuba. He was one of the organizers of the first Havana Biennial in 1984 and remained central to the curatorial team until he resigned in 1989. Since then, his activity turned to be mainly international: he has been traveling, lecturing and curating exhibitions in more than 80 countries. Mosquera was adjunct curator at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, from 1995 to 2009. Since 1995 he is advisor in the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kusten in [Amsterdam]. His publications include several books on art and art theory, and more than 600 articles, reviews and essays have appeared in numerous magazines, including: Art Nexus, Cahiers, Lápiz, Neue Bildende Kunst, Oxford Art Journal, Poliester, Third Text. Among other volumes, Mosquera has edited Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America and co-edited Over Here: International Perspectives on Art and Culture. His theoretical essays – which have been influential in discussing art’s cultural dynamics in an internationalized world, and contemporary Latin American art – are dispersed in English, but have been collected in books in Caracas and Madrid in Spanish, and in Chinese in Beijing. Mosquera was the Artistic Director of PHotoEspaña, Madrid (2011–2013), the Chief Curator of the 4th Poly/Graphic San Juan Triennial (2015-2016), co-curator of the 3rd Documents, Beijing (2016) and co-curator of the Guangzhou Image Triennial (2021).

Víctor Patricio de Landaluze, was a Spanish-born painter active for much of his career in Cuba.

Queloides is an ongoing cultural and curatorial project in Cuban art that seeks to highlight the persistence of racist stereotypes and ideas of racial difference in Cuban society and culture. Initiated in 1997 by artist Alexis Esquivel and by art critic Omar Pascual Castillo, who organized the exhibit Queloides I Parte, the project was later led by the late art critic Ariel Ribeaux Diago, who organized two important additional exhibits: Ni músicos ni deportistas, for which he wrote an award-winning essay, and Queloides (1999). Queloides or keloids are raised scars that, as many in Cuba believe, appear most frequently on the black skin. The title makes reference to the scars of racism, on the one hand, and to persistent popular beliefs that there are "natural" differences between whites and blacks.

Yoruba Americans are Americans of Yoruba descent. The Yoruba people are a West African ethnic group that predominantly inhabits southwestern Nigeria, with smaller indigenous communities in Benin and Togo.

Vodun art is associated with the West African Vodun religion of Nigeria, Benin, Togo and Ghana. The term is sometimes used more generally for art associated with related religions of West and Central Africa and of the African diaspora in Brazil, the Caribbean and the United States. Art forms include bocio, carved wooden statues that represent supernatural beings and may be activated through various ritual steps, and Asen, metal objects that attract spirits of the dead or other spirits and give them a temporary resting place. Vodun is assimilative, and has absorbed concepts and images from other parts of Africa, India, Europe and the Americas. Chromolithographs representing Indian deities have become identified with traditional Vodun deities and used as the basis for murals in Vodun temples. The Ouidah '92 festival, held in Benin in 1993, celebrated the removal of restrictions on Vodun in that country and began a revival of Vodun art.

The International Festival of Vodun Arts and Cultures, also known as the Ouidah Festival, was first held in Ouidah, Benin in February 1993, sponsored by UNESCO and the government of Benin. It celebrated the transatlantic Vodun religion, and was attended by priest and priestesses from Haiti, Cuba, Trinidad and Tobago, Brazil and the United States, as well as by government officials and tourists from Europe and the Americas. The festival was sponsored by the newly elected president of Benin, Nicéphore Soglo, who wanted to rebuild the connection with the Americas and celebrate the restoration of freedom of religion with the return to democracy. Artists from Benin, Haiti, Brazil and Cuba were given commissions to make sculptures and paintings related to Vodun and its variants in Africa and the African diaspora.

Santería is an Afro-Cuban religion that arose in the 19th century.