The Kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a regional power in the 18th century by expanding south to conquer key cities like Whydah belonging to the Kingdom of Whydah on the Atlantic coast which granted it unhindered access to the tricontinental triangular trade.

Vodun is a religion practiced by the Aja, Ewe, and Fon peoples of Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Béhanzin is considered the eleventh King of Dahomey, modern-day Republic of Benin. Upon taking the throne, he changed his name from Kondo.

The Fon people, also called Fon nu, Agadja or Dahomey, are a Gbe ethnic group. They are the largest ethnic group in Benin found particularly in its south region; they are also found in southwest Nigeria and Togo. Their total population is estimated to be about 3,500,000 people, and they speak the Fon language, a member of the Gbe languages.

Nana Buluku, also known as Nana Buruku, Nana Buku or Nanan-bouclou, is the female supreme being in the West African traditional religion of the Fon people and the Ewe people (Togo). She is one of the most influential deities in West African theology, and one shared by many ethnic groups other than the Fon people, albeit with variations. For example, she is called the Nana Bukuu among the Yoruba people and the Olisabuluwa among Igbo people but described differently, with some actively worshiping her while some do not worship her and worship the gods originating from her.

The Aja also spelled Adja are an ethnic group native to south-western Benin and south-eastern Togo. According to oral tradition, the Aja migrated to southern Benin in the 12th or 13th century from Tado on the Mono River, and c. 1600, three brothers, Kokpon, Do-Aklin, and Te-Agbanlin, split the ruling of the region then occupied by the Aja amongst themselves: Kokpon took the capital city of Great Ardra, reigning over the Allada kingdom; Do-Aklin founded Abomey, which would become capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey; and Te-Agbanlin founded Little Ardra, also known as Ajatche, later called Porto Novo by Portuguese traders and the current capital city of Benin.

Ouidah or Whydah and known locally as Glexwe, formerly the chief port of the Kingdom of Whydah, is a city on the coast of the Republic of Benin. The commune covers an area of 364 km2 (141 sq mi) and as of 2002 had a population of 76,555 people.

The traditional beliefs and practices of African people are highly diverse beliefs that include various ethnic religions. Generally, these traditions are oral rather than scriptural and are passed down from one generation to another through folk tales, songs, and festivals, and include beliefs in spirits and higher and lower gods, sometimes including a supreme being, as well as the veneration of the dead, and use of magic and traditional African medicine. Most religions can be described as animistic with various polytheistic and pantheistic aspects. The role of humanity is generally seen as one of harmonizing nature with the supernatural.

A manbo is a priestess in the Haitian Vodou religion. Haitian Vodou's conceptions of priesthood stem from the religious traditions of enslaved people from Dahomey, in what is today Benin. For instance, the term manbo derives from the Fon word nanbo. Like their West African counterparts, Haitian manbos are female leaders in Vodou temples who perform healing work and guide others during complex rituals. This form of female leadership is prevalent in urban centers such as Port-au-Prince. Typically, there is no hierarchy among manbos and oungans. These priestesses and priests serve as the heads of autonomous religious groups and exert their authority over the devotees or spiritual servants in their hounfo (temples).

Tambor de Mina is an Afro-Brazilian religious tradition, practiced mainly in the Brazilian states of Maranhão, Piauí, Pará and the Amazon rainforest.

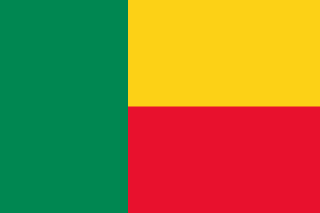

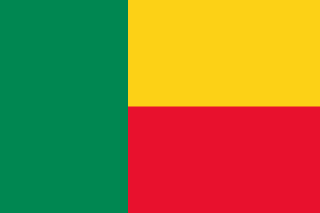

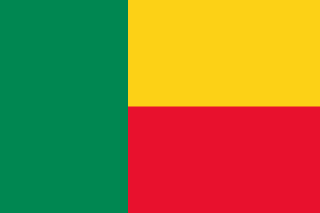

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Benin:

Christianity is the largest religion in Benin, with substantial populations of Muslims and adherents of traditional faiths. According to the most recent 2020 estimate, the population of Benin is 52.2% Christian, 24.6% Muslim, 17.9 Animist and 5.3% follows other faiths or has no religion.

Francisco Félix de Souza was a Brazilian slave trader who was deeply influential in the regional politics of pre-colonial West Africa. He founded Afro-Brazilian communities in areas that are now part of those countries, and went on to become the "chachá" of Ouidah, a title that conferred no official powers but commanded local respect in the Kingdom of Dahomey, where, after being jailed by King Adandozan of Dahomey, he helped Ghezo ascend the throne in a coup d'état. He became chacha to the new king, a curious phrase that has been explained as originating from his saying "(...) já, já.", a Portuguese phrase meaning something will be done right away.

The Tammari people, or Batammariba, or Tamberma or Somba also known as Otamari or Ottamari, are an Oti–Volta-speaking people of the Atakora Department of Benin where they are also known as Somba and neighboring areas of Togo, where they are officially known as Ta(m)berma. They are famous for their two-story fortified houses, known as Tata Somba, in which the ground floor houses livestock at night, internal alcoves are used for cooking, and the upper floor contains a rooftop courtyard that is used for drying grain, as well as containing sleeping quarters and granaries. These evolved by adding an enclosing roof to the clusters of huts, joined by a connecting wall that is typical of Gur-speaking areas of West Africa.

Benin, officially the Republic of Benin, is a country in Western Africa. It borders Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east and Burkina Faso and Niger to the north; its short coastline to the south leads to the Bight of Benin. Its size is just over 110000 km2 with a population of almost 8500000. Its capital is the Yoruba founded city of Porto Novo, but the seat of government is the Fon city of Cotonou. About half the population live below the international poverty line of US$1.25 per day.

Biography

Suzanne Preston Blier is an American art historian who currently serves as Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University with appointments in both the History of Art and Architecture department and the department of African and African American studies. She is also a member of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science and a faculty associate at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Her work focuses primarily on African art, architecture, and culture.

Hwanjile was a high priest and kpojito of the African Kingdom of Dahomey, in what is now Benin.

The International Festival of Vodun Arts and Cultures, also known as the Ouidah Festival, was first held in Ouidah, Benin in February 1993, sponsored by UNESCO and the government of Benin. It celebrated the transatlantic Vodun religion, and was attended by priest and priestesses from Haiti, Cuba, Trinidad and Tobago, Brazil and the United States, as well as by government officials and tourists from Europe and the Americas. The festival was sponsored by the newly elected president of Benin, Nicéphore Soglo, who wanted to rebuild the connection with the Americas and celebrate the restoration of freedom of religion with the return to democracy. Artists from Benin, Haiti, Brazil and Cuba were given commissions to make sculptures and paintings related to Vodun and its variants in Africa and the African diaspora.

Joseph Kossivi Ahiator is a Ghanaian artist, described as the most "sought-after India spirit temple painter in Bénin, Togo and Ghana". His work is in the possession of the Fowler Museum. He is noted for his print “The King of Mami Wata” (2005) and his Tchamba temple mural in Lomé.