Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite. Washington was from the last generation of Black American leaders born into slavery and became the leading voice of the former slaves and their descendants. They were newly oppressed in the South by disenfranchisement and the Jim Crow discriminatory laws enacted in the post-Reconstruction Southern states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tuskegee University, formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

An African American is a citizen or resident of the United States who has origins in any of the black populations of Africa. African American-related topics include:

The National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) is an American organization that was formed in July 1896 at the First Annual Convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Women in Washington, D.C., United States, by a merger of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, the Woman's Era Club of Boston, and the Colored Women's League of Washington, DC, at the call of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. From 1896 to 1904 it was known as the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). It adopted the motto "Lifting as we climb", to demonstrate to "an ignorant and suspicious world that our aims and interests are identical with those of all good aspiring women." When incorporated in 1904, NACW became known as the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC).

Mary Church Terrell was an American civil rights activist, journalist, teacher and one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree. She taught in the Latin Department at the M Street School —the first African American public high school in the nation—in Washington, DC. In 1895, she was the first African-American woman in the United States to be appointed to the school board of a major city, serving in the District of Columbia until 1906. Terrell was a charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) and the Colored Women's League of Washington (1892). She helped found the National Association of Colored Women (1896) and served as its first national president, and she was a founding member of the National Association of College Women (1923).

Mary Burnett Talbert was an American orator, activist, suffragist and reformer. In 2005, Talbert was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

The National Afro-American Council was the first nationwide civil rights organization in the United States, created in 1898 in Rochester, New York. Before its dissolution a decade later, the Council provided both the first national arena for discussion of critical issues for African Americans and a training ground for some of the nation's most famous civil rights leaders in the 1910s, 1920s, and beyond.

An Alabama's Colored Women's Club refers to any member of the Alabama Federation of Colored Women's Club, including the "Ten Times One is Ten Club", the Tuskegee Women's Club, and the Anna M. Duncan Club of Montgomery. These earliest clubs united and created the Alabama Federation of Colored Women's Club in 1899. By 1904, there were more than 26 clubs throughout Alabama. The most active ones were in Birmingham, Selma, Mobile, Tuskegee, Tuscaloosa, Eufaula, Greensboro, and Mt. Megis.

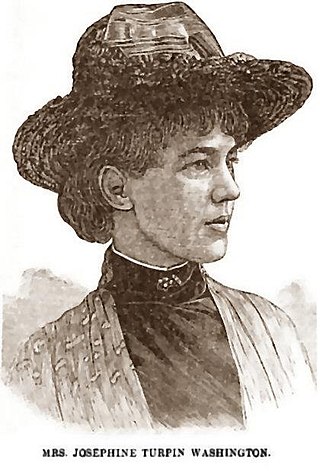

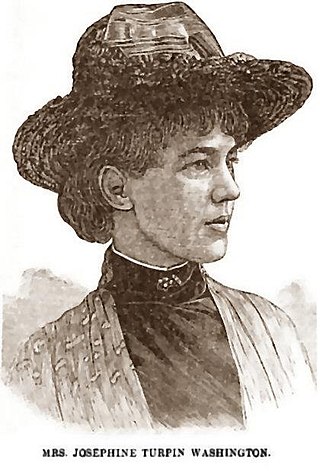

Josephine Turpin Washington was an African-American writer and teacher. A long-time educator and a frequent contributor, Washington devised articles to magazines and newspapers typically concerning some aspect of racism in America. Washington was a great-granddaughter of Mary Jefferson Turpin, a paternal aunt of Thomas Jefferson.

Ella Lillian Davis Browne Mahammitt was an American journalist, civil rights activist, and women's rights activist from Omaha, Nebraska. She was editor of the black weekly newspaper The Enterprise, president of Omaha's Colored Women's Club, and an officer of local branches of the Afro-American League. In 1895, she was vice-president of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, headed by Margaret James Murray, and in 1896 was a committee member of the successor organization, the National Association of Colored Women, under president Mary Church Terrell.

The First National Conference of the Colored Women of America was a three-day conference in Boston organized by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, a civil rights leader and suffragist. In August 1895, representatives from 42 African-American women's clubs from 14 states convened at Berkeley Hall for the purpose of creating a national organization. It was the first event of its kind in the United States.

The Woman's Era was the first national newspaper published by and for black women in the United States. Originally established as a monthly Boston newspaper, it became distributed nationally in 1894 and ran until January 1897, with Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin as editor and publisher. The Woman's Era played an important role in the national African American women's club movement.

Jessie Parkhurst Guzman was a writer, archivist, historian, educator, and college administrator, primarily at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. In her work at the Tuskegee Institute, particularly in the Department of Research and Records, she documented the lives of African Americans and maintained the Institute's lynching records.

Bess Bolden Walcott (1886-1988) was an American educator, librarian, museum curator and activist who helped establish the historical significance of the Tuskegee University. Recruited by Booker T. Washington to help him coordinate his library and teach science, she remained at the institute until 1962, but continued her service into the 1970s. Throughout her fifty-four year career at Tuskegee, she organized Washington's library, taught science and English at the institute, served as founder and editor of two of the major campus publications, directed public relations, established the Red Cross chapter, curated the George Washington Carver collection and museum and assisted in Tuskegee being placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Cornelia Bowen (1865-1934) was an African American teacher and school founder from Alabama. She was in the first graduating class of the Tuskegee Institute and went on to found the Mount Meigs Colored Institute as well as the Mt. Meigs Negro Boys' Reformatory. Based on the principles of the Tuskegee Institute, where she was trained, Bowen created industrial schools to teach students to thrive from their own industry. She was a member of both the state and national Colored Women's Federated Clubs and served as an officer of both organizations. She also was elected as the first woman president of the Alabama Negro Teacher's Association.

Jennie B. Moton (1879-1942) was an American educator and clubwoman. As a special field agent for the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) in the 1930s and 40s, she worked to improve the lives of rural African Americans in the South. She directed the department of Women's Industries at the Tuskegee Institute, presided over the Tuskegee Woman's Club, and was a two-term president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW).

Adella Hunt Logan was an African-American writer, educator, administrator and suffragist. Born during the Civil War, she earned her teaching credentials at Atlanta University, an historically black college founded by the American Missionary Association. She became a teacher at the Tuskegee Institute and became an activist for education and suffrage for women of color. As part of her advocacy, she published articles in some of the most noted black periodicals of her time.

Josephine Beall Willson Bruce was a women's rights activist in the late 1890s and early 1900s. She spent a majority of her time working for the National Organization of Afro-American Women. She was a prominent socialite in Washington, D.C. throughout most of her life where she lived with her husband, United States Senator Blanche Bruce. In addition to these accomplishments, she was the first black teacher in the public school system in Cleveland, and she eventually became a highly regarded educator at Tuskegee University in Alabama.

Dr. Rosa Slade Gragg was an American activist and politician. She founded the first black vocational school in Detroit, Michigan; and was the advisor to three United States presidents. She was inducted in 1987 into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame.

M. Cravath Simpson was an African-American activist and public speaker. After beginning her career as a singer, she studied to become a podiatrist, but is most known for her work to uplift the black community and combat lynching. Though she was based in Boston, Simpson spoke throughout the Northeastern and Midwestern United States urging recognition of the human rights of black citizens.