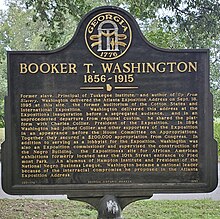

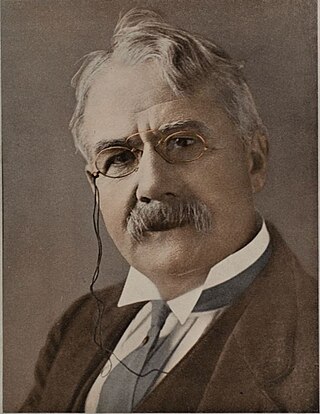

Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, and orator. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the primary leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision ruling that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that came to be known as "separate but equal". The decision legitimized the many state laws re-establishing racial segregation that had been passed in the American South after the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877. Such legally enforced segregation in the south lasted into the 1960s.

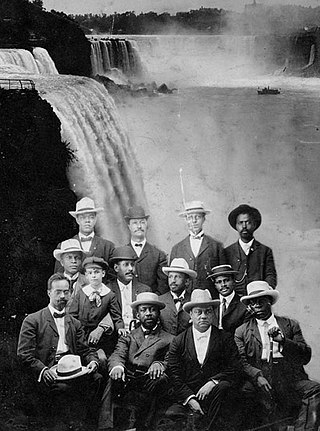

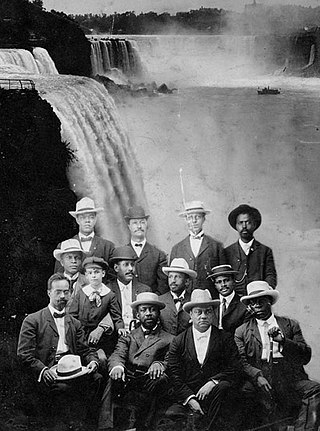

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. The Niagara Movement was organized to oppose racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Its members felt "unmanly" the policy of accommodation and conciliation, without voting rights, promoted by Booker T. Washington. It was named for the "mighty current" of change the group wanted to effect and took Niagara Falls as its symbol. The group did not meet in Niagara Falls, New York, but planned its first conference for nearby Buffalo. The Niagara Movement was the immediate predecessor of the NAACP.

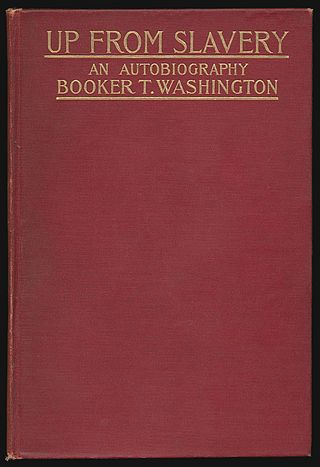

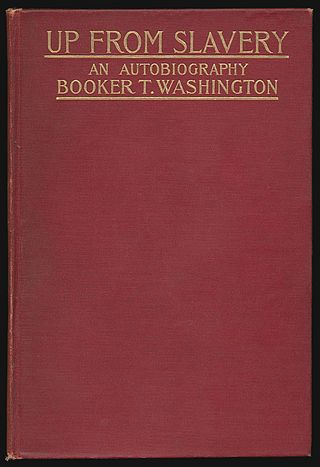

Up from Slavery is the 1901 autobiography of the American educator Booker T. Washington (1856–1915). The book describes his experience of working to rise up from being enslaved as a child during the Civil War, the obstacles he overcame to get an education at the new Hampton Institute, and his work establishing vocational schools like the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to help Black people and other persecuted people of color learn useful, marketable skills and work to pull themselves, as a race, up by the bootstraps. He reflects on the generosity of teachers and philanthropists who helped educate Black and Native Americans. He describes his efforts to instill manners, breeding, health and dignity into students. His educational philosophy stresses combining academic subjects with learning a trade. Washington explained that the integration of practical subjects is partly designed to "reassure the White community of the usefulness of educating Black people".

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce White supremacy. Their policy of Redemption was intended to oust the Radical Republicans, a coalition of freedmen, "carpetbaggers", and "scalawags". They were typically led by White yeomen and dominated Southern politics in most areas from the 1870s to 1910.

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

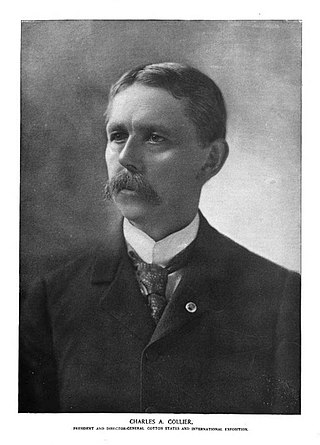

Charles Augustus Collier was an American banker, lawyer, and politician who served as Mayor of Atlanta, Georgia, from 1897 to 1899.

The Cotton States and International Exposition was a world's fair held in Atlanta, Georgia, United States in 1895. The exposition was designed "to foster trade between southern states and South American nations as well as to show the products and facilities of the region to the rest of the nation and Europe."

Rufus Brown Bullock was a Republican Party politician and businessman in Georgia. During the Reconstruction Era he served as the state's governor and called for equal economic opportunity and political rights for blacks and whites in Georgia. He also promoted public education for both, and encouraged railroads, banks, and industrial development. During his governorship he requested federal military help to ensure the rights of freedmen; this made him "the most hated man in the state", and he had to flee the state without completing his term. After returning to Georgia and being found "not guilty" of corruption charges, for three decades afterwards he was an esteemed private citizen.

What came to be known as the Atlanta Compromise stemmed from a speech given by Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute, to the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 18, 1895. It was first supported and later opposed by W. E. B. Du Bois and other African-American leaders.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the Black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

Frank Lebby Stanton, frequently credited as Frank L. Stanton, Frank Stanton or F. L. Stanton, was an American lyricist.

Miriam Elizabeth Benjamin was an American schoolteacher and inventor. In 1888, she obtained a patent for the Gong and Signal Chair for Hotels, becoming the second African-American woman to receive a patent.

The Double Conscious: Race & Rhetoric is a 2011 educational documentary compilation of speeches, by a number of prominent figures, dealing with race and racism in America.

African-American Georgians are residents of the U.S. state of Georgia who are of African American ancestry. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, African Americans were 31.2% of the state's population. Georgia has the second largest African American population in the United States following Texas. Georgia also has a gullah community. African slaves were brought to Georgia during the slave trade.

Lafayette M. Hershaw was a journalist, lawyer, and a clerk and law examiner for the United States General Land Office of the United States Department of the Interior. He was a key intellectual figure among African Americans in Atlanta in the 1880s and in Washington, D.C., from 1890 until his death. He was a leader of the intellectual social groups in the capital such as Bethel Literary and Historical Society and the Pen and Pencil Club. He was a strong supporter of W. E. B. Du Bois and was one of the thirteen organizers of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner to the NAACP. He was an officer of the D.C. Branch of the NAACP from its inception until 1928. He was also a founder of the Robert H. Terrell Law School and served as the school's president.

Orishatukeh Faduma was an Nigerian-American Christian missionary and educator who was also an advocate for African culture. He contributed to laying the foundation for the future development of African studies.

Irvine Garland Penn was an American educator, journalist, and lay leader in the Methodist Episcopal Church. He was the author of The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, published in 1891, and a coauthor with Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett of The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbia Exposition in 1893. In the late 1890s, he became an officer in the Methodist Episcopal Church and played an important role advocating for the interests of African Americans in the church until his death.

Black Kentuckians are residents of the state of Kentucky who are of African ancestry. The history of Blacks in the US state of Kentucky starts at the same time as the history of White Americans; Black Americans settled Kentucky alongside white explorers such as Daniel Boone. As of 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, African Americans make up 8.5% of Kentucky's population. Compared to the rest of the population, the African American census racial category is the 2nd largest.