A rapier or espada ropera is a type of sword used in Renaissance Spain to designate a sword with a straight, slender and sharply pointed two-edged long blade wielded in one hand. It was widely popular in Western Europe throughout the 16th and 17th centuries as a symbol of nobility or gentleman status.

A quarterstaff, also short staff or simply staff is a traditional European pole weapon, which was especially prominent in England during the Early Modern period.

A longsword is a type of European sword characterized as having a cruciform hilt with a grip for primarily two-handed use, a straight double-edged blade of around 80 to 110 cm, and weighing approximately 1 to 1.5 kg.

Stage combat, fight craft or fight choreography is a specialised technique in theatre designed to create the illusion of physical combat without causing harm to the performers. It is employed in live stage plays as well as operatic and ballet productions. With the advent of cinema and television the term has widened to also include the choreography of filmed fighting sequences, as opposed to the earlier live performances on stage. It is closely related to the practice of stunts and is a common field of study for actors. Actors famous for their stage fighting skills frequently have backgrounds in dance, gymnastics or martial arts training.

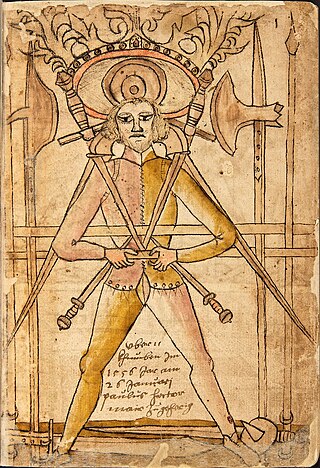

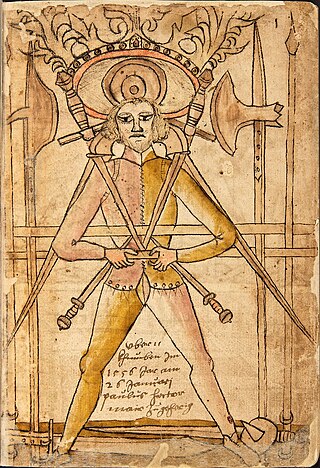

Royal Armouries Ms. I.33 is the earliest known surviving European fechtbuch, and one of the oldest surviving martial arts manuals dealing with armed combat worldwide. I.33 is also known as the Walpurgis manuscript, after a figure named Walpurgis shown in the last sequence of the manuscript, and "the Tower manuscript" because it was kept in the Tower of London during 1950-1996; also referred to as British Museum No. 14 E iii, No. 20, D. vi.

Johannes Liechtenauer was a German fencing master who had a great level of influence on the German fencing tradition in the 14th century.

Historical European martial arts (HEMA) are martial arts of European origin, particularly using arts formerly practised, but having since died out or evolved into very different forms.

The German school of fencing is a system of combat taught in the Holy Roman Empire during the Late Medieval, German Renaissance, and early modern periods. It is described in the contemporary Fechtbücher written at the time. The geographical center of this tradition was in what is now Southern Germany including Augsburg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg. During the period in which it was taught, it was known as the Kunst des Fechtens, or the "Art of Fighting". The German school of fencing focuses primarily on the use of the two-handed longsword; it also describes the use of many other weapons, including polearms, medieval daggers, messers, and the staff, as well as describing mounted combat and unarmed grappling (ringen).

The English language terminology used in the classification of swords is imprecise and has varied widely over time. There is no historical dictionary for the universal names, classification, or terminology of swords; a sword was simply a single-edged or double-edged knife.

In martial arts, a waster is a practice weapon, usually a sword, and usually made out of wood, though nylon (plastic) wasters are also available. Nylon is safer than wood, due to it having an adequate amount of flex for thrusts to be generally safe, unlike wooden wasters. Even a steel feder has more flex than most wooden wasters. The use of wood or nylon instead of metal provides an economic option for initial weapons training and sparring, at some loss of genuine experience. A weighted waster may be used for a sort of strength training, theoretically making the movements of using an actual sword comparatively easier and quicker, though modern sports science shows that an athlete would most optimally train with an implement which is closest to the same weight, balance, and shape of the tool they will be using. Wasters as wooden practice weapons have been found in a variety of cultures over a number of centuries, including ancient China, Ireland, Iran, Scotland, Rome, Egypt, medieval and renaissance Europe, Japan, and into the modern era in Europe and the United States. Over the course of time, wasters took a variety of forms not necessarily influenced by chronological succession, ranging from simple sticks to clip-point dowels with leather basket hilts to careful replicas of real swords.

The term Italian school of swordsmanship is used to describe the Italian style of fencing and edged-weapon combat from the time of the first extant Italian swordsmanship treatise (1409) to the days of classical fencing.

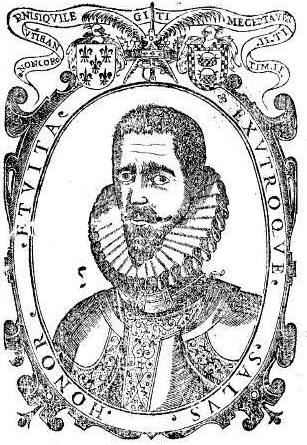

Joachim Meyer was a self-described Freifechter living in the then Free Imperial City of Strasbourg in the 16th century and the author of a fechtbuch Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens first published in 1570.

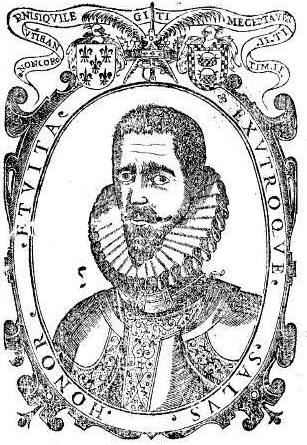

Don Luis Pacheco de Narváez (1570–1640) was a Spanish writer on destreza, the Spanish art of fencing.

The oldest surviving manual on western swordsmanship dates back to the 14th century, although historical references date fencing schools back to the 12th century.

La Verdadera Destreza is the conventional term for the Spanish tradition of fencing of the early modern period. The word destreza literally translates to 'dexterity' or 'skill, ability', and thus la verdadera destreza to 'the true skill' or 'the true art'.

There is some evidence on historical fencing as practised in Scotland in the Early Modern Era, especially fencing with the Scottish basket-hilted broadsword during the 17th to 18th centuries.

Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens or, in English: A Foundational Description of the Art of Fencing: A Thorough Description of the Free, Knightly and Noble Art of Fencing, Showing Various Customary Defenses, Affected and Put Forth with Many Handsome and Useful Drawings is a German fencing manual that was published in 1570. Its author was the Freifechter Joachim Meyer. This manual was made for and was dedicated to Meyer's patron Count Palatine Johann Casimir. This fechtbuch builds on his earlier work, a manuscript written in 1560 - the MS A.4°.2, and presents a complex, multi-weapon treatise. Meyer's complete system often marks the end of and the compilation of the German fencing system in the Johannes Liechtenauer tradition. It is the only fechtbuch in the Liechtenauer tradition that was written for both laymen and beginners of the art.

Schola Gladiatoria (SG) is a historical European martial arts (HEMA) group based in Ealing, west London, Great Britain, founded in 2001 and led by Matt Easton. It provides organized instruction in the serious study and practice of historical European swordplay. Schola seeks to be consistent with the methodology of the ancient European fencing schools by combining scholarship and research into the teachings of the historical masters, with the practical knowledge gained through solo and partnered drilling, and free play (sparring).

Libro de las grandezas de la espada is a 16th-century Spanish treatise on fencing written by Don Luis Pacheco de Narváez, who is considered one of the founding fathers of Spanish fencing (destreza) and the disciple of Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza.

Don Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza,, Jerónimo de Carranza, Portuguese: Hieronimo de Carança; c. 1539 – c. 1600 or 1608) was a Spanish nobleman, humanist, scientist, one of the most famous fencers, and the creator of the Spanish school of fencing, destreza. He was the author of the treatise on fencing De la Filosofía de las Armas y de su Destreza y la Aggression y Defensa Cristiana from 1569, published in 1582. Carranza created the ideal of a poet and a warrior, which became the main guide to life for noblemen.