In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. Often, mimicry functions to protect a species from predators, making it an anti-predator adaptation. Mimicry evolves if a receiver perceives the similarity between a mimic and a model and as a result changes its behaviour in a way that provides a selective advantage to the mimic. The resemblances that evolve in mimicry can be visual, acoustic, chemical, tactile, or electric, or combinations of these sensory modalities. Mimicry may be to the advantage of both organisms that share a resemblance, in which case it is a form of mutualism; or mimicry can be to the detriment of one, making it parasitic or competitive. The evolutionary convergence between groups is driven by the selective action of a signal-receiver or dupe. Birds, for example, use sight to identify palatable insects and butterflies, whilst avoiding the noxious ones. Over time, palatable insects may evolve to resemble noxious ones, making them mimics and the noxious ones models. In the case of mutualism, sometimes both groups are referred to as "co-mimics". It is often thought that models must be more abundant than mimics, but this is not so. Mimicry may involve numerous species; many harmless species such as hoverflies are Batesian mimics of strongly defended species such as wasps, while many such well-defended species form Müllerian mimicry rings, all resembling each other. Mimicry between prey species and their predators often involves three or more species.

Brood parasitism is a subclass of parasitism and phenomenon and behavioural pattern of certain animals, brood parasites, that rely on others to raise their young. The strategy appears among birds, insects and fish. The brood parasite manipulates a host, either of the same or of another species, to raise its young as if it were its own, usually using egg mimicry, with eggs that resemble the host's.

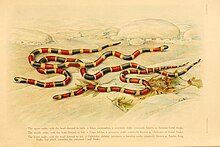

Batesian mimicry is a form of mimicry where a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a predator of them both. It is named after the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, after his work on butterflies in the rainforests of Brazil.

Anti-predator adaptations are mechanisms developed through evolution that assist prey organisms in their constant struggle against predators. Throughout the animal kingdom, adaptations have evolved for every stage of this struggle, namely by avoiding detection, warding off attack, fighting back, or escaping when caught.

The viceroy is a North American butterfly. It was long thought to be a Batesian mimic of the monarch butterfly, but since the viceroy is also distasteful to predators, it is now considered a Müllerian mimic instead.

Müllerian mimicry is a natural phenomenon in which two or more well-defended species, often foul-tasting and sharing common predators, have come to mimic each other's honest warning signals, to their mutual benefit. The benefit to Müllerian mimics is that predators only need one unpleasant encounter with one member of a set of Müllerian mimics, and thereafter avoid all similar coloration, whether or not it belongs to the same species as the initial encounter. It is named after the German naturalist Fritz Müller, who first proposed the concept in 1878, supporting his theory with the first mathematical model of frequency-dependent selection, one of the first such models anywhere in biology.

Aposematism is the advertising by an animal to potential predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defenses which make the prey difficult to kill and eat, such as toxicity, venom, foul taste or smell, sharp spines, or aggressive nature. These advertising signals may take the form of conspicuous coloration, sounds, odours, or other perceivable characteristics. Aposematic signals are beneficial for both predator and prey, since both avoid potential harm.

Ant mimicry or myrmecomorphy is mimicry of ants by other organisms. Ants are abundant all over the world, and potential predators that rely on vision to identify their prey, such as birds and wasps, normally avoid them, because they are either unpalatable or aggressive. Spiders are the most common ant mimics. Additionally, some arthropods mimic ants to escape predation, while others mimic ants anatomically and behaviourally to hunt ants in aggressive mimicry. Ant mimicry has existed almost as long as ants themselves; the earliest ant mimics in the fossil record appear in the mid Cretaceous alongside the earliest ants. Indeed one of the earliest, Burmomyrma, was initially classified as an ant.

In zoology, automimicry, Browerian mimicry, or intraspecific mimicry, is a form of mimicry in which the same species of animal is imitated. There are two different forms.

An eyespot is an eye-like marking. They are found in butterflies, reptiles, cats, birds and fish.

Aggressive mimicry is a form of mimicry in which predators, parasites, or parasitoids share similar signals, using a harmless model, allowing them to avoid being correctly identified by their prey or host. Zoologists have repeatedly compared this strategy to a wolf in sheep's clothing. In its broadest sense, aggressive mimicry could include various types of exploitation, as when an orchid exploits a male insect by mimicking a sexually receptive female, but will here be restricted to forms of exploitation involving feeding. For example, indigenous Australians who dress up as and imitate kangaroos when hunting would not be considered aggressive mimics, nor would a human angler, though they are undoubtedly practising self-decoration camouflage. Treated separately is molecular mimicry, which shares some similarity; for instance a virus may mimic the molecular properties of its host, allowing it access to its cells. An alternative term, Peckhamian mimicry, has been suggested, but it is seldom used.

Animal colouration is the general appearance of an animal resulting from the reflection or emission of light from its surfaces. Some animals are brightly coloured, while others are hard to see. In some species, such as the peafowl, the male has strong patterns, conspicuous colours and is iridescent, while the female is far less visible.

Emsleyan mimicry, also called Mertensian mimicry, describes an unusual type of mimicry where a deadly prey mimics a less dangerous species.

Chemical mimicry is a type of biological mimicry involving the use of chemicals to dupe an operator.

Cleaning symbiosis is a mutually beneficial association between individuals of two species, where one removes and eats parasites and other materials from the surface of the other. Cleaning symbiosis is well-known among marine fish, where some small species of cleaner fish, notably wrasses but also species in other genera, are specialised to feed almost exclusively by cleaning larger fish and other marine animals. Other cleaning symbioses exist between birds and mammals, and in other groups.

Adaptive Coloration in Animals is a 500-page textbook about camouflage, warning coloration and mimicry by the Cambridge zoologist Hugh Cott, first published during the Second World War in 1940; the book sold widely and made him famous.

In evolutionary biology, mimicry in plants is where a plant organism evolves to resemble another organism physically or chemically, increasing the mimic's Darwinian fitness. Mimicry in plants has been studied far less than mimicry in animals, with fewer documented cases and peer-reviewed studies. However, it may provide protection against herbivory, or may deceptively encourage mutualists, like pollinators, to provide a service without offering a reward in return.

Deception in animals is the transmission of misinformation by one animal to another, of the same or different species, in a way that propagates beliefs that are not true.

Animal coloration provided important early evidence for evolution by natural selection, at a time when little direct evidence was available. Three major functions of coloration were discovered in the second half of the 19th century, and subsequently used as evidence of selection: camouflage ; mimicry, both Batesian and Müllerian; and aposematism.

Locomotor mimicry is a subtype of Batesian mimicry in which animals avoid predation by mimicking the movements of another species phylogenetically separated. This can be in the form of mimicking a less desirable species or by mimicking the predator itself. Animals can show similarity in swimming, walking, or flying of their model animals.