Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (yazata) Mithra, the Roman Mithras is linked to a new and distinctive imagery, with the level of continuity between Persian and Greco-Roman practice debated. The mysteries were popular among the Imperial Roman army from about the 1st to the 4th century CE.

Dura-Europos was a Hellenistic, Parthian, and Roman border city built on an escarpment 90 metres above the southwestern bank of the Euphrates river. It is located near the village of Salhiyé, in present-day Syria. Dura-Europos was founded around 300 BC by Seleucus I Nicator, who founded the Seleucid Empire as one of the Diadochi of Alexander the Great. In 113 BC, Parthians conquered the city, and held it, with one brief Roman intermission, until 165 AD. Under Parthian rule, it became an important provincial administrative centre. The Romans decisively captured Dura-Europos in 165 AD and greatly enlarged it as their easternmost stronghold in Mesopotamia, until it was captured by the Sasanian Empire after a siege in 256–57 AD. Its population was deported, and the abandoned city eventually became covered by sand and mud and disappeared from sight.

Franz-Valéry-Marie Cumont was a Belgian archaeologist and historian, a philologist and student of epigraphy, who brought these often isolated specialties to bear on the syncretic mystery religions of Late Antiquity, notably Mithraism.

A Mithraeum(Latin pl. Mithraea), sometimes spelled Mithreum and Mithraion, is a Mithraic temple, erected in classical antiquity by the worshippers of Mithras. Most Mithraea can be dated between 100 BC and 300 AD, mostly in the Roman Empire.

Tauroctony is a modern name given to the central cult reliefs of the Mithraic Mysteries in the Roman Empire. The imagery depicts Mithras killing a bull, hence the name tauroctony after the Greek word tauroktonos. A tauroctony is distinct from the sacrifice of a bull in ancient Rome called a taurobolium; the taurobolium was mainly part of the unrelated cult of Cybele.

The Roman cult of Mithras had connections with other pagan deities, syncretism being a prominent feature of Roman paganism. Almost all Mithraea contain statues dedicated to gods of other cults, and it is common to find inscriptions dedicated to Mithras in other sanctuaries, especially those of Jupiter Dolichenus. Mithraism was not an alternative to other pagan religions, but rather a particular way of practising pagan worship; and many Mithraic initiates can also be found worshipping in the civic religion, and as initiates of other mystery cults.

Parthian art was Iranian art made during the Parthian Empire from 247 BC to 224 AD, based in the Near East. It has a mixture of Persian and Hellenistic influences. For some time after the period of the Parthian Empire, art in its styles continued for some time. A typical feature of Parthian art is the frontality of the people shown. Even in narrative representations, the actors do not look at the object of their action, but at the viewer. These are features that anticipate the art of medieval Europe and Byzantium.

Yarhibol or Iarhibol is an Aramean god who was worshiped mainly in ancient Palmyra, a city in central Syria. He was depicted with a solar nimbus and styled "lord of the spring". He normally appears alongside Bel, who was a co-supreme god of Palmyra, and Aglibol, one of the other top Palmyrene gods.

The Temple of the Gadde is a temple in the modern-day Syrian city of Dura-Europos, located near the agora. It contained reliefs dedicated to the tutelary deities of Dura-Europos and the nearby city of Palmyra, after whom the temple was named by its excavators. The temple was excavated between 1934 and January 1936 by the French/American expedition of Yale University, led by Michael Rostovtzeff.

The Temple of Bel, also known as the Temple of the Palmyrene gods, was located in Dura Europos, an ancient city on the Euphrates, in modern Syria. The temple was established in the first century BC and is celebrated primarily for its wall paintings. Despite the modern names of the structure, it is uncertain which gods were worshipped in the structure. Under Roman rule, the temple was dedicated to the Emperor Alexander Severus. In that period, the temple was located within the military camp of the XXth Palmyrene cohort.

The Temple of Zeus Cyrius stood in the city of Dura-Europos (Syria) and The construction of the original temenos is dated by the inscriptions above its altar and on its cult reliefs to the end of the second decade of the first century after Christ. It was excavated in 1934 by a joint French-American expedition.

The Temple of Zeus Theos at Dura Europos was built in the second century AD and was among the most important sanctuaries of the city. The structure was located in the centre of the settlement. It had an area of around 37 m2 and took up half an insula. It was excavated by an American-French team between December 1933 and March 1939.

The Statue of Hercules was discovered in the Temple of Zeus Megistos in Dura-Europos during the 1935–1937 excavations undertaken by Yale University and the French Academy. The statue dates from the period of Roman rule at Dura-Europos. It is now in the possession of the Yale Art Gallery.

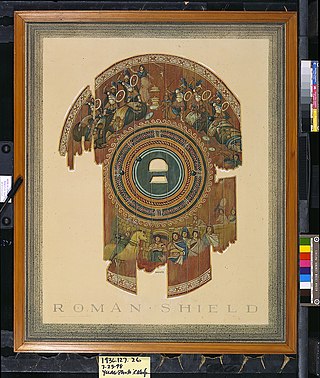

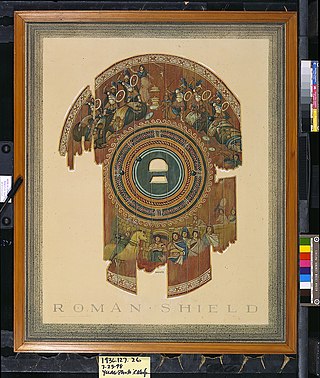

The scutum from Dura-Europos is the only surviving semi-cylindrical shield (scutum) from Roman times. It is now in the Yale University Art Gallery. The shield was found in the excavation campaign of 1928/37 on Tower 19 of Dura-Europos. The city was besieged by the Sassanids in 256, eventually captured and destroyed. The dry climate enables very good conservation conditions for organic materials such as wood. Since the city housed a Roman garrison and was lost during a siege, a particularly large number of weapons were found during the excavations.

The so-called Dolicheneum is a temple in Dura Europos in the east of today's Syria, where Jupiter Dolichenus and god called Zeus Helios Mithras Turmasgade may have been worshiped. The remains of the temple were excavated in 1935/36, but results were never fully published.

The Temple of Aphlad was an ancient temple located in the southwestern corner of Dura Europos, and dedicated to the god Aphlad. Aphlad was originally a Semitic Mesopotamian god from the city of Anath, and presence of his cult in Dura is revealing of its religious and cultural diversity. The temple itself consists of an open courtyard with multiple scattered rooms and altars, similar to the Temple of Bel, which was located in an analogous position in the northwestern corner of Dura.

The temple of Artemis Azzanathkona is located in Dura Europos in the east of present-day Syria, and was dedicated to a syncretic belief of Artemis and Azzanathkona.

The Temple of Zeus Megistos is in Dura-Europos in the east of the city in a part of the city that is modernly referred to as the Acropolis. It was one of the main temples of the city, the oldest construction phases of which perhaps go back to the time when the city was under Greek rule. The temple is not well preserved and the results of its excavations are not fully published. Several times the temple has been the target of excavations. The first excavations took place in 1928–37. The ceramics have hardly been recorded, which makes dating the older layers more difficult. The excavators presented some reconstructions of the oldest Greek temple. In particular, the more recent excavations from 1992 and 2002 raise doubts about older reconstructions and interpretations.

The Homeric shield is one of three figural painted shields found together in an embankment within a Roman garrison during the excavations of Dura-Europos. Dura-Europos was a border city of various empires throughout antiquity, and in modern archaeology is noteworthy for its large amount of well-preserved artifacts. Having been virtually untouched for centuries, and with favorable soil, an unusual amount of organic material has been preserved at Dura-Europos. This shield and those found alongside it date from the middle of the 3rd century CE, a period in which a large portion of the city was co-opted as a Roman military base. The shields were deliberately discarded unfinished during the Sassanian siege of Dura Europos. It is widely believed to depict two scenes from the Trojan war: the admission of the Trojan horse into Troy, and the subsequent sack of the city. It is one of few examples of Roman painting on wood, and one of very few Roman painted wooden shields to have survived from antiquity. The shield has now deteriorated beyond most detail being discernible to the naked eye. This is due to the unintended adverse effects of a binding agent applied to the shield in the 1930s in the hopes of preserving the pigmentation.

The building that is referred to as the Priests' House, or House of Priests, at Dura-Europos near the village of Salhiyah in eastern present-day Syria, is one of three buildings that was excavated in block H2. It is hypothesized to be the home of priests from the Temple of Atargatis based on its proximity to the two neighboring temples and graffiti found in the third Excavation season.