Related Research Articles

The 1912 United States presidential election was the 32nd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 5, 1912. Democratic Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey unseated incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft while defeating former President Theodore Roosevelt and Socialist Party nominee Eugene V. Debs.

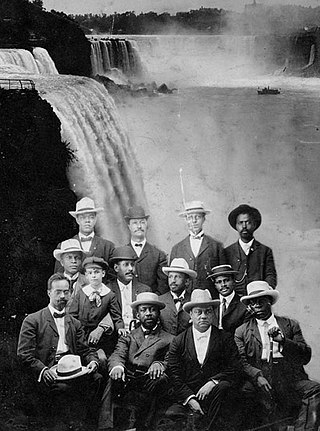

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. The Niagara Movement was organized to oppose racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Its members felt "unmanly" the policy of accommodation and conciliation, without voting rights, promoted by Booker T. Washington. It was named for the "mighty current" of change the group wanted to effect and took Niagara Falls as its symbol. The group did not meet in Niagara Falls, New York, but planned its first conference for nearby Buffalo. The Niagara Movement was the immediate predecessor of the NAACP.

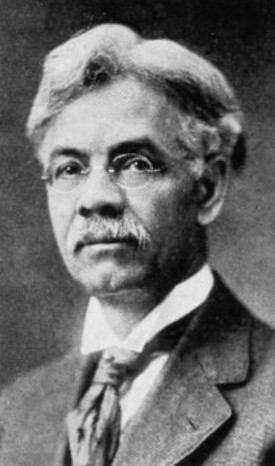

William Monroe Trotter, sometimes just Monroe Trotter, was a newspaper editor and real estate businessman based in Boston, Massachusetts. An activist for African-American civil rights, he was an early opponent of the accommodationist race policies of Booker T. Washington, and in 1901 founded the Boston Guardian, an independent African-American newspaper he used to express that opposition. Active in protest movements for civil rights throughout the 1900s and 1910s, he also revealed some of the differences within the African-American community. He contributed to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

Archibald Henry Grimké was an African-American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He graduated from freedmen's schools, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and Harvard Law School, and served as American Consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. He was an activist for the rights of Black Americans, working in Boston and Washington, D.C. He was a national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as president of its Washington, D.C. chapter.

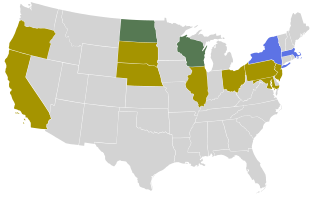

The Progressive Party was a third party in the United States formed in 1912 by former president Theodore Roosevelt after he lost the presidential nomination of the Republican Party to his former protégé turned rival, incumbent president William Howard Taft. The new party was known for taking advanced positions on progressive reforms and attracting leading national reformers. The party was also ideologically deeply connected with America's radical-liberal tradition.

The Brownsville affair, or the Brownsville raid, was an incident of racial discrimination that occurred in 1906 in the Southwestern United States due to resentment by white residents of Brownsville, Texas, of the Buffalo Soldiers, black soldiers in a segregated unit stationed at nearby Fort Brown. When a white bartender was killed and a white police officer wounded by gunshots one night, townspeople accused the members of the African-American 25th Infantry Regiment. Although their commanders said the soldiers had been in the barracks all night, evidence was allegedly planted against the men.

From January 23 to June 4, 1912, delegates to the 1912 Republican National Convention were selected through a series of primaries, caucuses, and conventions to determine the party's nominee for President in the 1912 election. Incumbent President William Howard Taft was chosen over former President Theodore Roosevelt. Taft's victory at the national convention precipitated a fissure in the Republican Party, with Roosevelt standing for the presidency as the candidate of an independent Progressive Party, and the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson over the divided Republicans.

William Henry Lewis was an African-American pioneer in athletics, law and politics. Born in Virginia to freedmen, he graduated from Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he had been one of the first African-American college football players. After going to Harvard Law School and continuing to play football, Lewis was the first African American in the sport to be selected as an All-American.

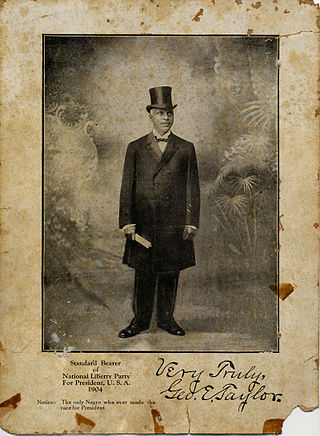

George Edwin Taylor was an American journalist, editor, political activist, and politician. In 1904, he was the candidate of the National Negro Liberty Party for President of the United States. He was the first African American to run for president.

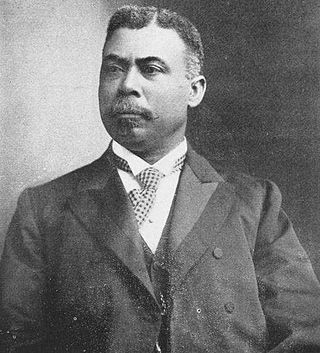

Judson Whitlocke Lyons was an American politician and attorney. He became the second African American attorney in Georgia in 1884, and later served as the Register of the Treasury.

Lafayette M. Hershaw was a journalist, lawyer, and a clerk and law examiner for the United States General Land Office of the United States Department of the Interior. He was a key intellectual figure among African Americans in Atlanta in the 1880s and in Washington, D.C., from 1890 until his death. He was a leader of the intellectual social groups in the capital such as Bethel Literary and Historical Society and the Pen and Pencil Club. He was a strong supporter of W. E. B. Du Bois and was one of the thirteen organizers of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner to the NAACP. He was an officer of the D.C. Branch of the NAACP from its inception until 1928. He was also a founder of the Robert H. Terrell Law School and served as the school's president.

Henry Lincoln Johnson was an American attorney and politician from the state of Georgia. He is best remembered as one of the most prominent African-American Republicans of the first two decades of the 20th century and as a leader of the dominant black-and-tan faction of the Republican Party of Georgia. He was appointed by President William Howard Taft as Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, at the time regarded as the premier political patronage position reserved for black Americans, and one of four appointees known as Taft's "Black Cabinet".

Freeman H. M. Murray was an intellectual, civil rights activist, and journalist in Washington D.C. and Alexandria, Virginia. He was active in promoting black home-ownership, opposing Jim Crow laws and lynching, and supporting positive representation of African Americans in public art. He was a founding member of the Niagara Movement and was an editor of its journal, the Horizon, along with W. E. B. Du Bois and Lafayette M. Hershaw. Alongside his other work, Murray was an important intellectual leader and wrote an influential book of art criticism. In this, Murray was one of the first historians of African American art. His work expressed a desire that art take seriously the representation of African Americans and that slavery not be overlooked in favor of representation of heroes and glory in public art.

Butler Roland Wilson (1861–1939) was an attorney, civil rights activist, and humanitarian based in Boston, Massachusetts. Born in Georgia, he came to Boston for law school and lived there for the remainder of his life. For over fifty years, he worked to combat racial discrimination in Massachusetts. He was one of the first African-American members of the American Bar Association. Wilson was a founding member and president of the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

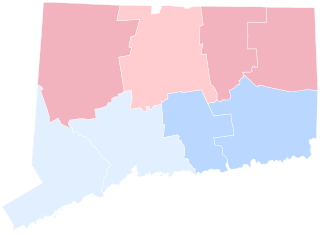

The 1912 United States presidential election in Connecticut took place on November 5, 1912, as part of the 1912 United States presidential election which was held throughout all contemporary 48 states. Voters chose seven representatives, or electors to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president.

The 1912 United States presidential election in North Carolina took place on November 5, 1912, as part of the 1912 United States presidential election. North Carolina voters chose 12 representatives, or electors, to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president. Like all former Confederate states, North Carolina would during its “Redemption” develop a politics based upon Jim Crow laws, disfranchisement of its African-American population and dominance of the Democratic Party. However, unlike the Deep South, the Republican Party possessed sufficient historic Unionist white support from the mountains and northwestern Piedmont to gain a stable one-third of the statewide vote total in general elections even after blacks lost the right to vote.

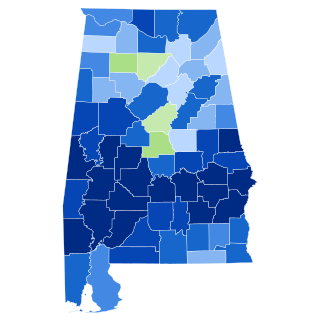

The 1912 United States presidential election in Alabama took place on November 5, 1912, as part of the 1912 United States presidential election. Alabama voters chose twelve representatives, or electors, to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president.

Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) was the prominent American scholar who served as president of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, as governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913, and as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. He was a Democrat. While Wilson's tenure is often noted for progressive achievement, his time in office was one of unprecedented regression in racial equality.

John Milton Waldron was a clergyman and civil rights leader in the United States. He led the NAACP's Washington D.C. branch.

References

- 1 2 3 "William Monroe Trotter Challenges President Wilson". The White House Historical Association. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Schneider, Mark (January 21, 1997). Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 1890-1920. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 118–121. ISBN 978-1-55553-296-3 – via Project Muse.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schneider, Mark (January 21, 1997). Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 1890-1920 . Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-55553-296-3 – via Project Muse.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Timeline of William Monroe Trotter's Life". The William Monroe Trotter Multicultural Center. University of Michigan. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- 1 2 Lehr, Dick (2015-11-27). "The Racist Legacy of Woodrow Wilson". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ↑ Lewis, David Levering (1993). W. E. B. Du Bois, 1868-1919: Biography of a Race. Macmillan. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-8050-3568-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Meier, August. "The Negro and the Democratic Party, 1875-1915." Phylon (1940-1956) 17, no. 2 (1956): 186. via JSTOR, accessed February 11, 2024.

- 1 2 3 Meier, August. "The Negro and the Democratic Party, 1875-1915." Phylon (1940-1956) 17, no. 2 (1956): 188. via JSTOR, accessed February 11, 2024.

- 1 2 "Letter from The National Negro American Political League to W. E. B. Du Bois, June 24, 1908". credo.library.umass.edu. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- 1 2 D.C (1908). Jim-Crow Car Laws and the Republican Party. Washington, D.C.: National Negro American Political League.

- ↑ Lee, B. F. "Negro Organizations." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 49 (1913): 137. via JSTOR.

- ↑ "Fifty Years of Physical Freedom and Political Bondage, 1862-1912: This Jubilee Year is a Good Time to Strike for Political Liberty! "Equal Rights and Opportunities for All American Citizens."". Washington, D.C.: National Independent Political League. 1912.

- 1 2 Waldron, John Milton; Harkless, John D. (1912). "The Political Situation in a Nut-shell: Some Un-colored Truths for Colored Voters". Washington, D.C.: National Independent Political League.

- 1 2 "The Case Against Taft and Roosevelt from the Standpoint of the Colored Voters". Washington, D.C.: National Independent Political League. 1912.

- ↑ "Wilson and Trotter: Beyond the Oval Office". Wilson Center. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ↑ "Meetings". The Crisis. 8 (5): 218 – via Smithsonian Institution.

- 1 2 ""Birth of a Nation"". US History Scene. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ↑ Meier, August. "The Negro and the Democratic Party, 1875-1915." Phylon (1940-1956) 17, no. 2 (1956): 191. via JSTOR, accessed February 11, 2024.

- ↑ "A Collection of Booklets and Circulars Relating to the Campaign of the National Independent Political League in National Politics for the Year 1912". 1912.

- ↑ "The Second Emancipation of the Race: The Colored Man Learning to Use His Ballot for His Own Protection, Supporting Men and Measures Rather Than Parties: An Interview Published in the Virginian Pilot and Norfolk Landmark, August 31, 1912". Washington, D.C.: National Independent Political League. 1912.