The National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) is an American organization that was formed in July 1896 at the First Annual Convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Women in Washington, D.C., United States, by a merger of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, the Woman's Era Club of Boston, and the Colored Women's League of Washington, DC, at the call of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. From 1896 to 1904 it was known as the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). It adopted the motto "Lifting as we climb", to demonstrate to "an ignorant and suspicious world that our aims and interests are identical with those of all good aspiring women." When incorporated in 1904, NACW became known as the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC).

Mary Terrell was an American civil rights activist, journalist, teacher and one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree. She taught in the Latin Department at the M Street School —the first African American public high school in the nation—in Washington, DC. In 1895, she was the first African-American woman in the United States to be appointed to the school board of a major city, serving in the District of Columbia until 1906. Terrell was a charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) and the Colored Women's League of Washington (1892). She helped found the National Association of Colored Women (1896) and served as its first national president, and she was a founding member of the National Association of College Women (1923).

George Henry White was an American attorney and politician, elected as a Republican U.S. Congressman from North Carolina's 2nd congressional district between 1897 and 1901. He later became a banker in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and in Whitesboro, New Jersey, an African-American community he co-founded. White was the last African-American Congressman during the beginning of the Jim Crow era and the only African American to serve in Congress during his tenure.

Timothy Thomas Fortune was an American orator, civil rights leader, journalist, writer, editor and publisher. He was the highly influential editor of the nation's leading black newspaper The New York Age and was the leading economist in the black community. He was a long-time adviser to Booker T. Washington and was the editor of Washington's first autobiography, The Story of My Life and Work. Fortune's philosophy of militant agitation on behalf of the rights of black people laid one of the foundations of the Civil Rights Movement.

The National Afro-American League was formed on January 25, 1890, by Timothy Thomas Fortune. Preceding the foundation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the organization dedicated itself to racial solidarity and self-help.

The National Negro Committee was created in response to the Springfield race riot of 1908 against the black community in Springfield, Illinois. Prominent black activists and white progressives called for a national conference to discuss African-American civil rights. They met to address the social, economic, and political rights of African Americans. This gathering served as the predecessor to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was formally named during the second meeting in May 1910.

Bishop Alexander Walters was an American clergyman and civil rights leader. Born enslaved in Bardstown, Kentucky, just before the Civil War, he rose to become a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church at the age of 33, then president of the National Afro-American Council, the nation's largest civil rights organization, at the age of 40, serving in that post for most of the next decade.

The American Negro Academy (ANA), founded in Washington, DC in 1897, was the first organization in the United States to support African-American academic scholarship. It operated until 1928, and encouraged African Americans to undertake classical academic studies and liberal arts.

Lafayette M. Hershaw was a journalist, lawyer, and a clerk and law examiner for the United States General Land Office of the United States Department of the Interior. He was a key intellectual figure among African Americans in Atlanta in the 1880s and in Washington, D.C., from 1890 until his death. He was a leader of the intellectual social groups in the capital such as Bethel Literary and Historical Society and the Pen and Pencil Club. He was a strong supporter of W. E. B. Du Bois and was one of the thirteen organizers of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner to the NAACP. He was an officer of the D.C. Branch of the NAACP from its inception until 1928. He was also a founder of the Robert H. Terrell Law School and served as the school's president.

Richard W. Thompson was a journalist and public servant in Indiana and Washington, D.C. He was at various times an editor or managing editor of the Indianapolis Leader, the Indianapolis World, the Indianapolis Freeman and the Washington D.C. Colored American. He was published as a general correspondent in The Colored American, The Washington Post, the Indianapolis Freeman, the Indianapolis World, Atlanta Age, Baltimore Afro-American Ledger, the Cincinnati Rostrum, the Charleston West Virginia Advocate, the Philadelphia Tribune and the Chicago Monitor. His longest-lasting relationship was with the Indianapolis Freeman. In 1896, the black paper, The Leavenworth Herald, edited by Blanche Ketene Bruce, called Thompson the "best newspaper correspondent on the colored press."

The First National Conference of the Colored Women of America was a three-day conference in Boston organized by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, a civil rights leader and suffragist. In August 1895, representatives from 42 African-American women's clubs from 14 states convened at Berkeley Hall for the purpose of creating a national organization. It was the first event of its kind in the United States.

Robert Heberton Terrell was an attorney and the second African American to serve as a justice of the peace in Washington, DC. In 1911 he was appointed as a judge to the District of Columbia Municipal Court by President William Howard Taft; he was one of four African-American men appointed to high office and considered his "Black Cabinet". He was reappointed as judge under succeeding administrations, including that of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Ferdinand Lee Barnett was an American journalist, lawyer, and civil rights activist in Chicago, beginning in the late Reconstruction era.

William Henry Steward was a civil rights activist from Louisville, Kentucky. In February 1876, he was appointed the first black letter carrier in Kentucky. He was the leading layman of the General Association of Negro Baptists in Kentucky and played a key role in the founding of Simmons College of Kentucky by the group in 1879. He continued to play an important role in the college during his life. He was also co-founder of the American Baptist, a journal associated with the group, and Steward went on to be the journal's editor. He was a leader in Louisville civic and public life, and played a role in extending educational opportunities in the city to black children. In 1897, his political associations led to his appointment as judge of registration and election for the Fifteenth Precinct of the Ninth Ward, overseeing voter registration for the election. This was the first appointment of an African American to such a position in Kentucky. He was elected president of the Afro-American Press Association in the 1890s He was a close associate of Booker T. Washington, and in the late 1890s and early 1900s, Steward was a prominent member of the National Afro-American Council, which was dominated by Washington. He was president of the council from 1904 to 1905. He was a lifelong opponent of segregation and was frequently involved in anti-Jim Crow law activities. In 1914 he helped found a Louisville branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he left in 1920 to become a key player in the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC). He was also a prominent freemason and twice elected Worshipful Master of the Grand Lodge of Kentucky.

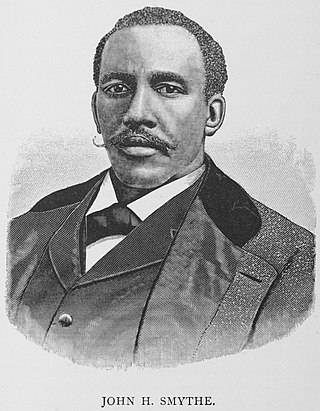

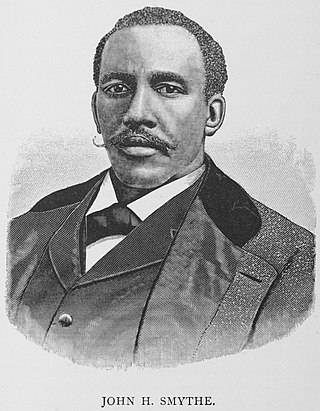

John H. Smythe was an American diplomat who served as the United States ambassador to Liberia from 1878 to 1881 and from 1882 to 1885. Before his appointment, he had various clerkships in the federal government in Washington, DC, and in Wilmington, North Carolina. Later in his life he took part in a number of leading African American organizations and was president of a Reformatory School outside of Richmond, Virginia.

John Campbell Dancy was an American politician, journalist, and educator in North Carolina and Washington, D.C. For many years he was the editor of African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion church newspapers Star of Zion and then Zion Quarterly. In 1897 he was appointed collector of customs at Wilmington, North Carolina, but was chased out of town in the Wilmington insurrection of 1898, in part for his activity in the National Afro-American Council which he helped found that year and of which he was an officer. He then moved to Washington, D.C., where he served as Recorder of Deeds from 1901 to 1910. His political appointments came in part as a result of the influence of his ally, Booker T. Washington.

Coralie Franklin Cook was an American educator, public speaker, and government official. She is also the first known descendant among those enslaved at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello estate to graduate from college. Cook, along with Mary Church Terrell, Anna J. Cooper, Angelina Weld Grimke, and Nannie Helen Burroughs, "exemplified the third generation of African American woman suffragists who related to both the Black and the white worlds."

Helen Appo Cook was a wealthy, prominent African-American community activist in Washington, D.C., and a leader in the women's club movement. Cook was a founder and president of the Colored Women's League, which consolidated with another organization in 1896 to become the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), an organization still active in the 21st century. Cook supported voting rights and was a member of the Niagara Movement, which opposed racial segregation and African American disenfranchisement. In 1898, Cook publicly rebuked Susan B. Anthony, president of the National Woman's Suffrage Association, and requested she support universal suffrage following Anthony's speech at a U.S. Congress House Committee on Judiciary hearing.

The Colored Women's League (CWL) of Washington, D.C., was a woman's club, organized by a group of African-American women in June 1892, with Helen Appo Cook as president. The primary mission of this organization was the national union of colored women. In 1896, the Colored Women's League and the Federation of Afro-American Women merged to form the National Association of Colored Women, with Mary Church Terrell as the first president.