Related Research Articles

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society, who often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown, also a freedman, also often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had 1,350 local chapters with around 250,000 members.

Theodore Dwight Weld was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known for his co-authorship of the authoritative compendium American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, published in 1839. Harriet Beecher Stowe partly based Uncle Tom’s Cabin on Weld's text; the latter is regarded as second only to the former in its influence on the antislavery movement. Weld remained dedicated to the abolitionist movement until slavery was ended by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

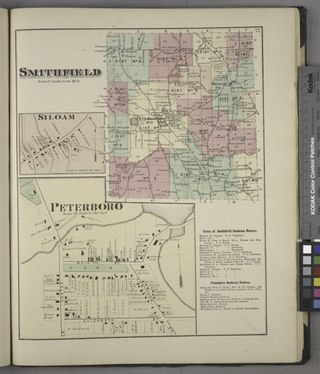

Peterboro, located approximately 25 miles (40 km) southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134.

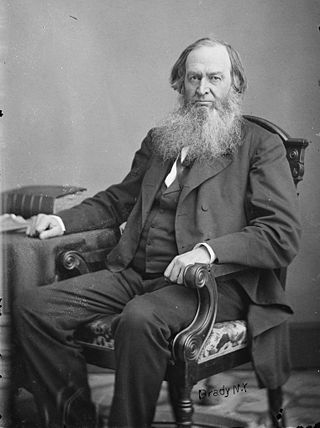

Gerrit Smith, also spelled Gerritt Smith, was an American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidate for President of the United States in 1848, 1856, and 1860. He served a single term in the House of Representatives from 1853 to 1854.

Henry Brewster Stanton was an American abolitionist, social reformer, attorney, journalist and politician. His writing was published in the New York Tribune, the New York Sun, and William Lloyd Garrison's Anti-Slavery Standard and The Liberator. He was elected to the New York State Senate in 1850 and 1851. His wife, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was a world renowned leading figure of the early women's rights movement.

Beriah Green Jr. was an American reformer, abolitionist, temperance advocate, college professor, minister, and head of the Oneida Institute. He was "consumed totally by his abolitionist views". Former student Alexander Crummell described him as a "bluff, kind-hearted man," a "master-thinker". Modern scholars have described him as "cantankerous", "obdurate," "caustic, belligerent, [and] suspicious". "He was so firmly convinced of his opinions and so uncompromising that he aroused hostility all about him."

Lewis Tappan was a New York abolitionist who dedicated his efforts to securing freedom for the enslaved Africans aboard the Amistad. He was born in Northampton, Massachusetts, into a Calvinist household.

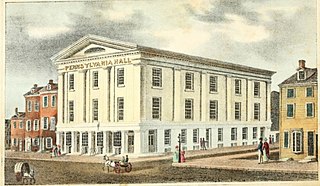

Pennsylvania Hall, "one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city," was an abolitionist venue in Philadelphia, built in 1837–38. It was a "Temple of Free Discussion", where antislavery, women's rights, and other reform lecturers could be heard. Four days after it opened it was destroyed by arson, the work of an anti-abolitionist mob.

Hart Leavitt was a Massachusetts merchant, landowner, legislator and abolitionist. Leavitt was the brother of Roger Hooker Leavitt, with whom he operated an Underground Railroad station in Charlemont, Massachusetts, where the two brothers, aided by a third sibling in New York, the reformer and abolitionist publisher Joshua Leavitt, sheltered escaped slaves on their journey northward. The Massachusetts homes of Hart Leavitt and his brother Roger Hooker are both listed today on the National Park Service's Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (1833–1840) was an abolitionist, interracial organization in Boston, Massachusetts, in the mid-19th century. "During its brief history ... it orchestrated three national women's conventions, organized a multistate petition campaign, sued southerners who brought slaves into Boston, and sponsored elaborate, profitable fundraisers."

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at which black men were just as welcome as whites. "Oneida was the seed of Lane Seminary, Western Reserve College, Oberlin and Knox colleges."

Ann Carroll Smith was an American abolitionist, mother of Elizabeth Smith Miller, and the spouse of Gerrit Smith. Her older brother was Henry Fitzhugh.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum is a museum located in Peterboro, New York, that honors American abolitionists by showcasing their work to end slavery, and the legacy of their struggle: the drive to end racism.

The Fugitive Slave Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. It was a fugitive slave meeting, the biggest ever held in the United States. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring Peterboro, New York, and called the meeting "in behalf of the New York State Vigilance Committee." Hostile newspaper reports refer to the meeting as "Gerrit Smith's Convention". Nearly fifty fugitives attended—the largest gathering of fugitive slaves in the nation's history.

Reuben Crandall, younger brother of educator Prudence Crandall, was a physician who was arrested in Washington, D.C., on August 10, 1835, on charges of "seditious libel and inciting slaves and free blacks to revolt", the libels being abolitionist materials portraying American slavery as cruel and sinful. He was nearly killed by a mob that wanted to hang him, and avoided that fate only because the mayor called out the militia. The Snow Riot ensued. Although a jury would find him innocent of all charges, his very high bail meant he remained in the Washington jail for almost eight months, where he contracted tuberculosis. He died soon after his release.

Thankful Southwick was an affluent Quaker abolitionist and women's rights activist in Boston, Massachusetts. Thankful was lifelong abolitionist who joined the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835 with her three daughters. She was present at both the 1835 Boston Mob and the Abolition Riot of 1836. During the 1840 schism in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Thankful sided with the Westons, Chapmans, Childs, Sergeants, and other radical Garrisonians to reestablish the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. She also later joined the New England Non Resistance Society.

The Ladies' New York City Anti-Slavery Society was a group of white Christian women in New York City who created an abolitionist society based on their religious views. At this time moral reforms were becoming popular and were encouraged by preachers. This group was founded in 1835 and had about 200 members. They felt as though they could help end slavery by using religion to pray and spread anti-slavery ideas, but this limited their activities, because they believed in the idea of separate spheres they did not participate in anything that was in the public sphere alongside men. Their society wrote letters, circulated petitions and held parlor lectures and conventions. There was a lot of controversy around this group within the women's anti-slavery movement because they did not allow black members. They also often fought against the women's rights movement. These views on women's rights eventually led to the end of the society because it was agreed that women should not be allowed to participate in organizations and voice their opinions alongside men. This led the New York City Anti-Slavery Society, which was male only, and the Ladies New York City Anti-Slavery Society to walk out of a planned debate that was held by the American Anti-Slavery Society. After this, the women's society supposedly served as an auxiliary of a new society the men created called the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. They did not have any recorded activity after this debate.

Anti-Slavery Society was a name used by various abolitionist groups including:

A symbolic day in the history of the American abolitionist movement was May 14, 1838. On that date two related events occurred: the inauguration in Philadelphia of Pennsylvania Hall, built to symbolize and facilitate the abolitionist movement, and the wedding of Theodore Weld and Angelina Grimké, "the wedding that ignited Philadelphia." The wedding was held that day because of the many out-of-town abolitionists present for the inauguration of the Hall.

References

- ↑ "Gerrit Smith". NATIONAL ABOLITION HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ↑ "Gerrit Smith", Wikipedia, 2024-05-31, retrieved 2024-06-03

- ↑ Brown, William E. (July 1998). "The Alvan Stewart Papers". University of Miami Libraries . Retrieved June 3, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Beriah Green". NATIONAL ABOLITION HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ↑ Myers, John L. (1962). "The Beginning of Anti-Slavery Agencies in New York State, 1833-1836". New York History. 43 (2): 149–181. ISSN 0146-437X. JSTOR 23158611.

- ↑ "Site of the Utica Riot (1835)". Clio. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ↑ "Utica Riot at 1835 Convention". Oneida County Freedom Trail. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the first annual meeting of the New-York State Anti-slavery Society, convened at Utica, October 19, 1836". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ↑ "Abolitionist Movement - Definition & Famous Abolitionists". HISTORY. 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ↑ Falls, Mailing Address: 136 Fall Street Seneca; Us, NY 13148 Phone: 315 568-0024 Contact. "Antislavery Connection - Women's Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Root, Erik S. "Virginia Slavery Debate of 1831–1832, The". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ↑ Muelder, Owen W. (2011-10-14). Theodore Dwight Weld and the American Anti-Slavery Society. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8853-7.

- ↑ Jay, William (1844) [1839]. A View of the Action of the Federal Government, In Behalf of Slavery (Original publisher: New-York, J.S. Taylor). Appendix: The Amistad Case by Joshua Leavitt. Utica, N.Y.: J.C. Jackson for the New York State Anti-Slavery Society. LCCN 05023101. OCLC 8529817.