In linguistics, declension is the changing of the form of a word, generally to express its syntactic function in the sentence, by way of some inflection. Declensions may apply to nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and articles to indicate number, case, gender, and a number of other grammatical categories. Meanwhile, the inflectional change of verbs is called conjugation.

Esperanto is the most widely used constructed language intended for international communication; it was designed with highly regular grammatical rules, and as such is considered an easy language to learn.

In linguistics, a noun class is a particular category of nouns. A noun may belong to a given class because of the characteristic features of its referent, such as gender, animacy, shape, but such designations are often clearly conventional. Some authors use the term "grammatical gender" as a synonym of "noun class", but others consider these different concepts. Noun classes should not be confused with noun classifiers.

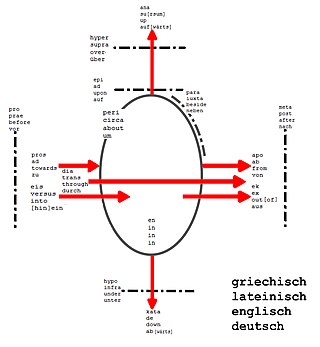

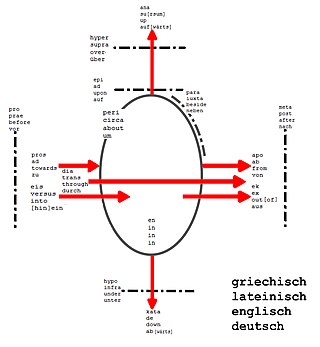

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word. Particularly in the study of languages, a prefix is also called a preformative, because it alters the form of the word to which it is affixed.

In grammar, a noun is a word that represents a concrete or abstract thing, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, and ideas. A noun may serve as an object or subject within a phrase, clause, or sentence.

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech is a category of words that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior, sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Wiyot or Soulatluk (lit. 'your jaw') is an Algic language spoken by the Wiyot people of Humboldt Bay, California. The language's last native speaker, Della Prince, died in 1962.

In linguistics, especially within generative grammar, phi features are the morphological expression of a semantic process in which a word or morpheme varies with the form of another word or phrase in the same sentence. This variation can include person, number, gender, and case, as encoded in pronominal agreement with nouns and pronouns. Several other features are included in the set of phi-features, such as the categorical features ±N (nominal) and ±V (verbal), which can be used to describe lexical categories and case features.

In linguistics, agreement or concord occurs when a word changes form depending on the other words to which it relates. It is an instance of inflection, and usually involves making the value of some grammatical category "agree" between varied words or parts of the sentence.

Tooro or Rutooro is a Bantu language spoken mainly by the Tooro people (Abatooro) from the Tooro Kingdom in western Uganda. There are three main areas where Tooro as a language is mainly used: Kabarole District, Kyenjojo District and Kyegegwa District. Tooro is unique among Bantu languages as it lacks lexical tone. It is most closely related to Runyoro.

Sesotho nouns signify concrete or abstract concepts in the language, but are distinct from the Sesotho pronouns.

The Sesotho parts of speech convey the most basic meanings and functions of the words in the language, which may be modified in largely predictable ways by affixes and other regular morphological devices. Each complete word in the Sesotho language must comprise some "part of speech."

This article presents a brief overview of the grammar of the Sesotho and provides links to more detailed articles.

Odia grammar is the study of the morphological and syntactic structures, word order, case inflections, verb conjugation and other grammatical structures of Odia, an Indo-Aryan language spoken in South Asia.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, and one can refer to the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, determiners, participles, prepositions and postpositions, numerals, articles, etc, as declension.

The American linguist Joseph Greenberg (1915–2001) proposed a set of linguistic universals based primarily on a set of 30 languages. The following list is verbatim from the list printed in the appendix of Greenberg's Universals of Language and "Universals Restated", sorted by context.

English nouns form the largest category of words in English, both in terms of the number of different words and in terms of how often they are used in typical texts. The three main categories of English nouns are common nouns, proper nouns, and pronouns. A defining feature of English nouns is their ability to inflect for number, as through the plural –s morpheme. English nouns primarily function as the heads of noun phrases, which prototypically function at the clause level as subjects, objects, and predicative complements. These phrases are the only English phrases whose structure includes determinatives and predeterminatives, which add abstract specifying meaning such as definiteness and proximity. Like nouns in general, English nouns typically denote physical objects, but they also denote actions, characteristics, relations in space, and just about anything at all. Taken all together, these features separate English nouns from the language's other lexical categories, such as adjectives and verbs.

Mungbam is a Southern Bantoid language of the Lower Fungom region of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but the language family is disputed. Good et al. uses a more accurate name, the 'Yemne-Kimbi group,' but proposes the term 'Beboid.'

Settla, or Settler Swahili, is a Swahili pidgin mainly spoken in large European settlements in Kenya and Zambia. It was used mainly by native English speaking European colonists for communication with the native Swahili speakers.

Swahili is a Bantu language which is native to or mainly spoken in the East African region. It has a grammatical structure that is typical for Bantu languages, bearing all the hallmarks of this language family. These include agglutinativity, a rich array of noun classes, extensive inflection for person, tense, aspect and mood, and generally a subject–verb–object word order.