Settlement

The history of Viking Age settlement of the Faroe Islands comes from the Færeyinga saga , a manuscript that is now lost. Portions of the tale were inscribed in three other sagas, such as Flateyjarbók and Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason . Similar to other sagas, the historical credibility of the Færeyinga saga is often questioned.

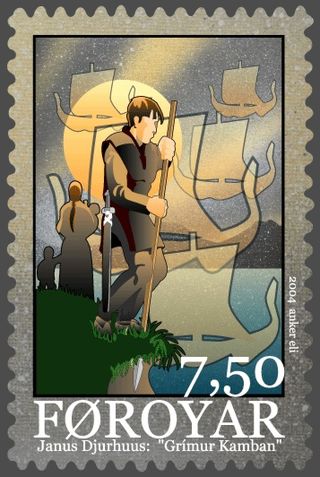

Both the Saga of Ólafr Tryggvason and Flateyjarbók claim a man named Grímur Kamban was the first man to discover the Faroe Islands. However, the two sources disagree on the year in which he left and the cause of his departure. Flateyjarbók details the emigration of Grímur Kamban as sometime during the reign of King Harald Hårfagre, between 872 and 930. [1] The Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason indicates that Kamban was residing in the Faroes long before the rule of Harald Hårfagre, and that other Norse were driven to the Faroe Islands due to his chaotic rule. [2]

This mass migration to the Faroe Islands shows a prior knowledge of the location of Norse settlements, furthering the claim of Grímur Kamban's settlement much earlier. While Kamban is recognized as the first Norse settler of the Faroe Islands (although his surname is of Gaelic origin), he actually re-settled the island. Writings from the Papar , an order of Irish monks, indicate their settling of the Faroes long before the Norse set foot there, only leaving due to ongoing Viking raids. [3]

Evidence

Excavation of a Viking Age farm found in the village of Kvívík on the island Streymoy, shows substantial evidence of farming done in a style common to the Faroe Islands. A longhouse was unearthed during an excavation alongside a byre (smaller dwelling intended to house livestock during winter). This find furthers the validity of the sagas by providing an aspect of the agricultural lifestyle being brought from Norway to the Faroe Islands. [4]

A more complete example of the agricultural Norse lifestyle on the Faroe Islands can be found at Toftanes, where a preserved longhouse was unearthed with its walls intact. The structure was made of stones and earth and measured 20 meters by 5 meters. A byre was attached to the eastern wall of the longhouse and both what has been determined to be an outhouse. Also on the north end was a house layered in old embers and charcoal, this room was determined to be for making fires. [5] [6]

The Sandavágur stone is a runestone discovered in 1917 in Sandvágur. The inscription tells of Torkil Onandarson from Rogaland who first settled that area. The 13th century relic is on display at Sandavágur Church. [7] [8]

Economy

Most of the evidence uncovered suggests that Norse communities residing on the Faroe Islands in the pre-Christian period were based heavily on crop cultivation and raising livestock. Bones of the livestock excavated show they raised sheep, goats, pigs and cows. Reliance on the land is indicated in certain names of settlements. The town of Akraberg (the name akur means cereal field) and Hoyvík (which means hay bay). [9] At Toftanes, materials Norse used for fishing, such as spindle whirls and lineor netsinkers suggesting a utilization of the islands natural resources for goods. Numerous wooden bowls and spoons made from local trees were uncovered as well as basalt and tufa. The Norse were masters of adapting to their surrounding environment and utilizing every resource possible. The settlers at Junkarinsfløttur had a diet heavy with native birds, particularly puffin. Although the Norse did rely heavily on the land of the Faroe Islands, they did not completely sever ties with their native Norway. [10]

Even though many of the Norse settlements on the Faroe Islands were due to the tyrannical reign Harald Hårfagre, the Norse still maintained contact with Scandinavia via trade. At Toftanes, a large quantity of steatite was unearthed in the form of fragments of bowls and saucepans. Steatite is not a material local to the Faroe Islands, but rather from Norway. In addition, due to difficulties with barley production, a community in Sandur is shown to have imported barley from Scandinavia. The Norse communities were not only in contact with Scandinavia. Two Hiberno-Norse ring pins and a Jewish bracelet identified as being from the Irish Sea region were discovered at Toftanes. The Norse who settled at the Faroe Islands appeared to have maintained the tradition of mercantilism throughout the Atlantic. [11]