Related Research Articles

Omaha is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about 10 mi (15 km) north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 40th-most populous city, Omaha had a population of 486,051 as of the 2020 census. It is the anchor of the eight-county Omaha–Council Bluffs metropolitan area, which extends into Iowa and is the 58th-largest metro area in the United States, with a population of 967,604. Furthermore, the greater Omaha–Council Bluffs–Fremont combined statistical area had 1,004,771 residents in 2020. Omaha is ranked as a global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network, which in 2020 gave it "sufficiency" status.

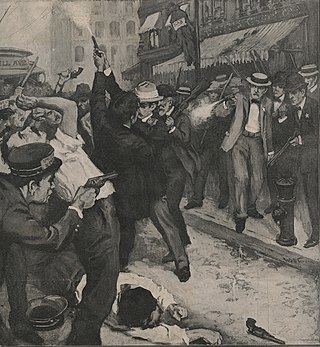

The community of Greeks in Omaha, Nebraska, has a history that extends back to the 1880s. After they originally moved to the city following work with the railroads, the community quickly grew and founded a substantial neighborhood in South Omaha that was colloquially referred to as "Greek Town." The community was replete with Greek bakers, barbers, grocers and cafes. After a 1909 mob attack on the community, Greek immigrants fled from Omaha. Today even though the Greek-American community is smaller than it was in 1909, it includes many prominent doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, business people and others who have achieved great success here. It currently maintains two Greek Orthodox Churches.

The timeline of racial tension in Omaha, Nebraska lists events in African-American history in Omaha. These included racial violence, but also include many firsts as the black community built its institutions. Omaha has been a major industrial city on the edge of what was a rural, agricultural state. It has attracted a more diverse population than the rest of the state. Its issues were common to other major industrial cities of the early 20th century, as it was a destination for 19th and 20th century European immigrants, and internal white and black migrants from the South in the Great Migration. Many early 20th-century conflicts arose out of labor struggles, postwar social tensions and economic problems, and hiring of later immigrants and black migrants as strikebreakers in the meatpacking and stockyard industries. Massive job losses starting in the 1960s with the restructuring of the railroad, stockyards and meatpacking industries contributed to economic and social problems for workers in the city.

Racial tension in Omaha, Nebraska occurred mostly because of the city's volatile mixture of high numbers of new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and African-American migrants from the Deep South. While racial discrimination existed at several levels, the violent outbreaks were within working classes. Irish Americans, the largest and earliest immigrant group in the 19th century, established the first neighborhoods in South Omaha. All were attracted by new industrial jobs, and most were from rural areas. There was competition among ethnic Irish, newer European immigrants, and African-American migrants from the South, for industrial jobs and housing. They all had difficulty adjusting to industrial demands, which were unmitigated by organized labor in the early years. Some of the early labor organizing resulted in increasing tensions between groups, as later arrivals to the city were used as strikebreakers. In Omaha as in other major cities, racial tension has erupted at times of social and economic strife, often taking the form of mob violence as different groups tried to assert power. Much of the early violence came out of labor struggles in early 20th century industries: between working class ethnic whites and immigrants, and blacks of the Great Migration. Meatpacking companies had used the latter for strikebreakers in 1917 as workers were trying to organize. As veterans returned from World War I, both groups competed for jobs. By the late 1930s, however, interracial teams worked together to organize the meatpacking industry under the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA). Unlike the AFL and some other industrial unions in the CIO, UPWA was progressive. It used its power to help end segregation in restaurants and stores in Omaha, and supported the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Women labor organizers such as Tillie Olsen and Rowena Moore were active in the meatpacking industry in the 1930s and 1940s, respectively.

Transportation in Omaha, Nebraska, includes most major modes, such as pedestrian, bicycle, automobile, bus, train and airplane. While early transportation consisted of ferries, stagecoaches, steamboats, street railroads, and railroads, the city's transportation systems have evolved to include the Interstate Highway System, parklike boulevards and a variety of bicycle and pedestrian trails. The historic head of several important emigrant trails and the First transcontinental railroad, its center as a national transportation hub earned Omaha the nickname "Gate City of the West" as early as the 1860s.

Railroads in Omaha, Nebraska, have been integral to the growth and development of the city, the state of Nebraska, the Western United States and the entire United States. The convergence of many railroad forces upon the city was by happenstance and synergy, as none of the Omaha leaders had a comprehensive strategy for bringing railroads to the city.

The 1905 Chicago Teamsters' strike was a sympathy strike and lockout by the United Brotherhood of Teamsters in the summer of 1905 in the city of Chicago, Illinois. The strike was initiated by a small clothing workers' union. But it soon spread as nearly every union in the city, including the Teamsters, supported the job action with sympathy strikes. Initially, the strike was aimed at the Montgomery Ward department store, but it affected almost every employer in the metropolitan region after the Teamsters walked out. The strike eventually pitted the Teamsters against the Employers' Association of Chicago, a broad coalition of business owners formed a few years earlier to oppose unionization in Chicago.

Gurdon Wallace Wattles was an early businessman, banker, and civic leader in Omaha, Nebraska, who became responsible for bankrolling much of early Hollywood. Wattles was said to possess "all the right credentials to direct Omaha's fortunes for the twentieth century in the post-pioneer era: humble beginnings, outstanding ability, a fine intellect, impeccable manners, driving ambition, and a ruthless streak."

The Wattles Estate is a former estate in the Hollywood area of Los Angeles, California. Wattles Mansion is a Mission Revival style mansion built in the estate in 1907 for wealthy Omaha banker Gurdon Wattles as his winter home; the estate contains a complex of gardens. It was sold to the city in 1968 and became the Wattles Garden Park, operated by the Department of Recreation and Parks. The mansion and gardens were designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1993.

The Omaha and Council Bluffs Railway and Bridge Company, known as O&CB, was incorporated in 1886 in order to connect Omaha, Nebraska with Council Bluffs, Iowa over the Missouri River. With a sanctioned monopoly over streetcar service in the two cities, the O&CB was among the earliest major electric street railway systems in the nation, and was one of the last streetcar operators in the U.S., making its last run in 1955.

The Camp Dump strike was a labor dispute that began on March 9, 1882 at the Burlington Yards in Omaha, Nebraska. The event pitted state militia against unionized strikers. It was reportedly the first strike by organized labor in Nebraska and the first Omaha riot to receive national attention.

The General Strike of 1910 was a labor strike by trolley workers of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company that grew to a citywide riot and general strike in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Indianapolis streetcar strike of 1913 and the subsequent police mutiny and riots was a civil conflict in Indianapolis, Indiana. The events began as a workers strike by the union employees of the Indianapolis Traction & Terminal Company and their allies on Halloween night, October 31, 1913. The company was responsible for public transportation in Indianapolis, the capital city and transportation hub of the U.S. state of Indiana. The unionization effort was being organized by the Amalgamated Street Railway Employees of America who had successfully enforced strikes in other major United States cities. Company management suppressed the initial attempt by some of its employees to unionize and rejected an offer of mediation by the United States Department of Labor, which led to a rapid rise in tensions, and ultimately the strike. Government response to the strike was politically charged, as the strike began during the week leading up to public elections. The strike effectively shut down mass transit in the city and caused severe interruptions of statewide rail transportation and the 1913 city elections.

The St. Louis streetcar strike of 1900 was a labor action, and resulting civil disruption, against the St. Louis Transit Company by a group of three thousand workers unionized by the Amalgamated Street Railway Employees of America.

From 1895 to 1929, streetcar strikes affected almost every major city in the United States. Sometimes lasting only a few days, these strikes were often "marked by almost continuous and often spectacular violent conflict," at times amounting to prolonged riots and weeks of civil insurrection.

The Los Angeles streetcar strike of 1919 was the most violent revolt against the open-shop policies of the Pacific Electric Railway Company in Los Angeles. Labor organizers had fought for over a decade to increase wages, decrease work hours, and legalize unions for streetcar workers of the Los Angeles basin. After having been denied unionization rights and changes in work policies by the National War Labor Board, streetcar workers broke out in massive protest before being subdued by local armed police force.

The Atlanta streetcar strike of 1916 was a labor strike involving streetcar operators for the Georgia Railway and Power Company in Atlanta, Georgia. Precipitated by previous strike action by linemen of Georgia Railway earlier that year, the strike began on September 30 and ended January 5 of the following year. The main goals of the strike included increased pay, shorter working hours, and union recognition. The strike ended with the operators receiving a wage increase, and subsequent strike action the following year lead to union recognition.

The 1910 streetcar strike was a union protest against labor practices by the Columbus Railway and Light Co. in Columbus, Ohio in 1910. The summertime strike began as peaceful protests, but led to thousands rioting throughout the city, injuring hundreds of people.

The 1916–1917 Springfield streetcar strike was a strike among streetcar workers in and around Springfield, Missouri. The strike went from October 5, 1916 to June 16, 1917 caused by the streetcar company's refusal to recognize the union. As a result, the union was recognized after 8 months of striking.

References

- ↑ Omaha History: At a Glance. Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Douglas County Historical Society. Retrieved 4/10/08.

- ↑ Leighton, G.R. (1939) Five Cities: The Story of Their Youth and Old Age. Ayer Publishing. p 201.

- ↑ Larsen and Cotrell. (2002) Omaha: The Gate City. University of Nebraska Press. p 136.

- ↑ "Omaha strike halts while Taft is here," The New York Times. September 21, 1909. Retrieved 4/20/08.

- ↑ Wattles, G. (1909) A Crime Against Labor: A brief history of the Omaha and Council Bluffs Street Railway Strike, 1909. Archive.org. Retrieved 4/26/08.

- ↑ "Militia in Omaha after fatal riot", The New York Times. June 16, 1935. Retrieved 4/16/08.

- ↑ "Nebraska Governor, Arriving by Plane, Orders Arbitration of Omaha Strike," The New York Times. June 17, 1935.

- ↑ Larsen and Cottrell (1997) Omaha: The Gate City. University of Nebraska Press. p 202-204.

- ↑ "Name arbitrators in Omaha strike; Both Sides Also Agree to Abide by Finding of Board in Trolley Walkout," The New York Times. June 19, 1935. Retrieved 4/20/08.

- ↑ "New riots in Omaha; Bricks Bombard Street Cars in Revived Strike Outbreak." The New York Times. June 30, 1935. Retrieved 4/21/08.

- ↑ "History at a Glance" Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine , Douglas County Historical Society. Retrieved June 18, 2007. p 93.