The Beer–Lambert law is commonly applied to chemical analysis measurements to determine the concentration of chemical species that absorb light. It is often referred to as Beer's law. In physics, the Bouguer–Lambert law is an empirical law which relates the extinction or attenuation of light to the properties of the material through which the light is travelling. It had its first use in astronomical extinction. The fundamental law of extinction is sometimes called the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert law or the Bouguer–Beer–Lambert law or merely the extinction law. The extinction law is also used in understanding attenuation in physical optics, for photons, neutrons, or rarefied gases. In mathematical physics, this law arises as a solution of the BGK equation.

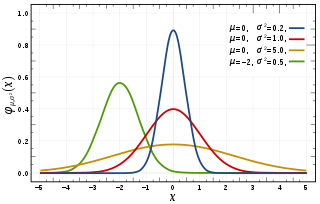

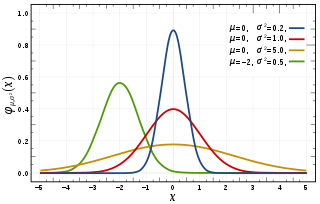

In probability theory and statistics, a normal distribution or Gaussian distribution is a type of continuous probability distribution for a real-valued random variable. The general form of its probability density function is The parameter is the mean or expectation of the distribution, while the parameter is the variance. The standard deviation of the distribution is . A random variable with a Gaussian distribution is said to be normally distributed, and is called a normal deviate.

Radiometry is a set of techniques for measuring electromagnetic radiation, including visible light. Radiometric techniques in optics characterize the distribution of the radiation's power in space, as opposed to photometric techniques, which characterize the light's interaction with the human eye. The fundamental difference between radiometry and photometry is that radiometry gives the entire optical radiation spectrum, while photometry is limited to the visible spectrum. Radiometry is distinct from quantum techniques such as photon counting.

The reflectance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in reflecting radiant energy. It is the fraction of incident electromagnetic power that is reflected at the boundary. Reflectance is a component of the response of the electronic structure of the material to the electromagnetic field of light, and is in general a function of the frequency, or wavelength, of the light, its polarization, and the angle of incidence. The dependence of reflectance on the wavelength is called a reflectance spectrum or spectral reflectance curve.

In optics, a Fabry–Pérot interferometer (FPI) or etalon is an optical cavity made from two parallel reflecting surfaces. Optical waves can pass through the optical cavity only when they are in resonance with it. It is named after Charles Fabry and Alfred Perot, who developed the instrument in 1899. Etalon is from the French étalon, meaning "measuring gauge" or "standard".

Absorbance is defined as "the logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted radiant power through a sample ". Alternatively, for samples which scatter light, absorbance may be defined as "the negative logarithm of one minus absorptance, as measured on a uniform sample". The term is used in many technical areas to quantify the results of an experimental measurement. While the term has its origin in quantifying the absorption of light, it is often entangled with quantification of light which is “lost” to a detector system through other mechanisms. What these uses of the term tend to have in common is that they refer to a logarithm of the ratio of a quantity of light incident on a sample or material to that which is detected after the light has interacted with the sample.

In optical physics, transmittance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in transmitting radiant energy. It is the fraction of incident electromagnetic power that is transmitted through a sample, in contrast to the transmission coefficient, which is the ratio of the transmitted to incident electric field.

In radiometry, radiance is the radiant flux emitted, reflected, transmitted or received by a given surface, per unit solid angle per unit projected area. Radiance is used to characterize diffuse emission and reflection of electromagnetic radiation, and to quantify emission of neutrinos and other particles. The SI unit of radiance is the watt per steradian per square metre. It is a directional quantity: the radiance of a surface depends on the direction from which it is being observed.

Variational Bayesian methods are a family of techniques for approximating intractable integrals arising in Bayesian inference and machine learning. They are typically used in complex statistical models consisting of observed variables as well as unknown parameters and latent variables, with various sorts of relationships among the three types of random variables, as might be described by a graphical model. As typical in Bayesian inference, the parameters and latent variables are grouped together as "unobserved variables". Variational Bayesian methods are primarily used for two purposes:

- To provide an analytical approximation to the posterior probability of the unobserved variables, in order to do statistical inference over these variables.

- To derive a lower bound for the marginal likelihood of the observed data. This is typically used for performing model selection, the general idea being that a higher marginal likelihood for a given model indicates a better fit of the data by that model and hence a greater probability that the model in question was the one that generated the data.

In radiometry, radiant intensity is the radiant flux emitted, reflected, transmitted or received, per unit solid angle, and spectral intensity is the radiant intensity per unit frequency or wavelength, depending on whether the spectrum is taken as a function of frequency or of wavelength. These are directional quantities. The SI unit of radiant intensity is the watt per steradian, while that of spectral intensity in frequency is the watt per steradian per hertz and that of spectral intensity in wavelength is the watt per steradian per metre —commonly the watt per steradian per nanometre. Radiant intensity is distinct from irradiance and radiant exitance, which are often called intensity in branches of physics other than radiometry. In radio-frequency engineering, radiant intensity is sometimes called radiation intensity.

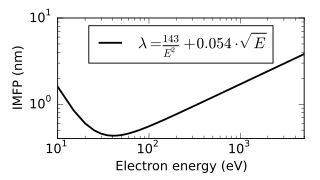

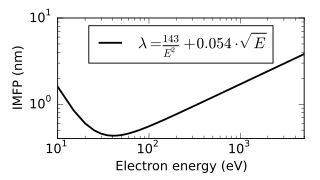

The inelastic mean free path (IMFP) is an index of how far an electron on average travels through a solid before losing energy.

Self-phase modulation (SPM) is a nonlinear optical effect of light–matter interaction. An ultrashort pulse of light, when travelling in a medium, will induce a varying refractive index of the medium due to the optical Kerr effect. This variation in refractive index will produce a phase shift in the pulse, leading to a change of the pulse's frequency spectrum.

In radiometry, radiant flux or radiant power is the radiant energy emitted, reflected, transmitted, or received per unit time, and spectral flux or spectral power is the radiant flux per unit frequency or wavelength, depending on whether the spectrum is taken as a function of frequency or of wavelength. The SI unit of radiant flux is the watt (W), one joule per second, while that of spectral flux in frequency is the watt per hertz and that of spectral flux in wavelength is the watt per metre —commonly the watt per nanometre.

In radiometry, radiant exitance or radiant emittance is the radiant flux emitted by a surface per unit area, whereas spectral exitance or spectral emittance is the radiant exitance of a surface per unit frequency or wavelength, depending on whether the spectrum is taken as a function of frequency or of wavelength. This is the emitted component of radiosity. The SI unit of radiant exitance is the watt per square metre, while that of spectral exitance in frequency is the watt per square metre per hertz (W·m−2·Hz−1) and that of spectral exitance in wavelength is the watt per square metre per metre (W·m−3)—commonly the watt per square metre per nanometre. The CGS unit erg per square centimeter per second is often used in astronomy. Radiant exitance is often called "intensity" in branches of physics other than radiometry, but in radiometry this usage leads to confusion with radiant intensity.

In electromagnetics, directivity is a parameter of an antenna or optical system which measures the degree to which the radiation emitted is concentrated in a single direction. It is the ratio of the radiation intensity in a given direction from the antenna to the radiation intensity averaged over all directions. Therefore, the directivity of a hypothetical isotropic radiator is 1, or 0 dBi.

Toroidal coordinates are a three-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system that results from rotating the two-dimensional bipolar coordinate system about the axis that separates its two foci. Thus, the two foci and in bipolar coordinates become a ring of radius in the plane of the toroidal coordinate system; the -axis is the axis of rotation. The focal ring is also known as the reference circle.

The Newman–Penrose (NP) formalism is a set of notation developed by Ezra T. Newman and Roger Penrose for general relativity (GR). Their notation is an effort to treat general relativity in terms of spinor notation, which introduces complex forms of the usual variables used in GR. The NP formalism is itself a special case of the tetrad formalism, where the tensors of the theory are projected onto a complete vector basis at each point in spacetime. Usually this vector basis is chosen to reflect some symmetry of the spacetime, leading to simplified expressions for physical observables. In the case of the NP formalism, the vector basis chosen is a null tetrad: a set of four null vectors—two real, and a complex-conjugate pair. The two real members often asymptotically point radially inward and radially outward, and the formalism is well adapted to treatment of the propagation of radiation in curved spacetime. The Weyl scalars, derived from the Weyl tensor, are often used. In particular, it can be shown that one of these scalars— in the appropriate frame—encodes the outgoing gravitational radiation of an asymptotically flat system.

The linear attenuation coefficient, attenuation coefficient, or narrow-beam attenuation coefficient characterizes how easily a volume of material can be penetrated by a beam of light, sound, particles, or other energy or matter. A coefficient value that is large represents a beam becoming 'attenuated' as it passes through a given medium, while a small value represents that the medium had little effect on loss. The (derived) SI unit of attenuation coefficient is the reciprocal metre (m−1). Extinction coefficient is another term for this quantity, often used in meteorology and climatology. Most commonly, the quantity measures the exponential decay of intensity, that is, the value of downward e-folding distance of the original intensity as the energy of the intensity passes through a unit thickness of material, so that an attenuation coefficient of 1 m−1 means that after passing through 1 metre, the radiation will be reduced by a factor of e, and for material with a coefficient of 2 m−1, it will be reduced twice by e, or e2. Other measures may use a different factor than e, such as the decadic attenuation coefficient below. The broad-beam attenuation coefficient counts forward-scattered radiation as transmitted rather than attenuated, and is more applicable to radiation shielding. The mass attenuation coefficient is the attenuation coefficient normalized by the density of the material.

In the study of heat transfer, absorptance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in absorbing radiant energy. It is the ratio of the absorbed to the incident radiant power.

Laser linewidth is the spectral linewidth of a laser beam.