The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

The Drake Passage is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile, Argentina and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean and extends into the Southern Ocean. The passage is named after the 16th-century English explorer and privateer Sir Francis Drake.

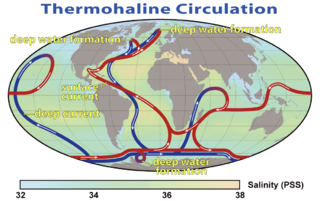

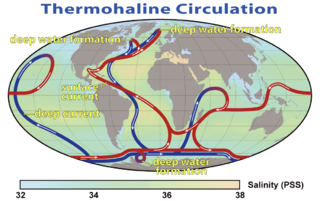

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective thermohaline derives from thermo- referring to temperature and -haline referring to salt content, factors which together determine the density of sea water. Wind-driven surface currents travel polewards from the equatorial Atlantic Ocean, cooling en route, and eventually sinking at high latitudes. This dense water then flows into the ocean basins. While the bulk of it upwells in the Southern Ocean, the oldest waters upwell in the North Pacific. Extensive mixing therefore takes place between the ocean basins, reducing differences between them and making the Earth's oceans a global system. The water in these circuits transport both energy and mass around the globe. As such, the state of the circulation has a large impact on the climate of the Earth.

In oceanography, a gyre is any large system of circulating ocean surface currents, particularly those involved with large wind movements. Gyres are caused by the Coriolis effect; planetary vorticity, horizontal friction and vertical friction determine the circulatory patterns from the wind stress curl (torque).

The North Equatorial Current (NEC) is a westward wind-driven current mostly located near the equator, but the location varies from different oceans. The NEC in the Pacific and the Atlantic is about 5°-20°N, while the NEC in the Indian Ocean is very close to the equator. It ranges from the sea surface down to 400 m in the western Pacific.

The Equatorial Counter Current is an eastward flowing, wind-driven current which extends to depths of 100–150 metres (330–490 ft) in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. More often called the North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC), this current flows west-to-east at about 3-10°N in the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Pacific basins, between the North Equatorial Current (NEC) and the South Equatorial Current (SEC). The NECC is not to be confused with the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC) that flows eastward along the equator at depths around 200 metres (660 ft) in the western Pacific rising to 100 metres (330 ft) in the eastern Pacific.

An abrupt climate change occurs when the climate system is forced to transition at a rate that is determined by the climate system energy-balance. The transition rate is more rapid than the rate of change of the external forcing, though it may include sudden forcing events such as meteorite impacts. Abrupt climate change therefore is a variation beyond the variability of a climate. Past events include the end of the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, Younger Dryas, Dansgaard-Oeschger events, Heinrich events and possibly also the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. The term is also used within the context of climate change to describe sudden climate change that is detectable over the time-scale of a human lifetime, possibly as the result of feedback loops within the climate system or tipping points.

The North Pacific Gyre (NPG) or North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG), located in the northern Pacific Ocean, is one of the five major oceanic gyres. This gyre covers most of the northern Pacific Ocean. It is the largest ecosystem on Earth, located between the equator and 50° N latitude, and comprising 20 million square kilometers. The gyre has a clockwise circular pattern and is formed by four prevailing ocean currents: the North Pacific Current to the north, the California Current to the east, the North Equatorial Current to the south, and the Kuroshio Current to the west. It is the site of an unusually intense collection of human-created marine debris, known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is part of a global thermohaline circulation in the oceans and is the zonally integrated component of surface and deep currents in the Atlantic Ocean. It is characterized by a northward flow of warm, salty water in the upper layers of the Atlantic, and a southward flow of colder, deep waters. These "limbs" are linked by regions of overturning in the Nordic and Labrador Seas and the Southern Ocean, although the extent of overturning in the Labrador Sea is disputed. The AMOC is an important component of the Earth's climate system, and is a result of both atmospheric and thermohaline drivers.

In climate science, a tipping point is a critical threshold that, when crossed, leads to large and often irreversible changes in the climate system. If tipping points are crossed, they are likely to have severe impacts on human society. Tipping behavior is found across the climate system, in ecosystems, ice sheets, and the circulation of the ocean and atmosphere.

The Great Salinity Anomaly (GSA) originally referred to an event in the late 1960s to early 1970s where a large influx of freshwater from the Arctic Ocean led to a salinity anomaly in the northern North Atlantic Ocean, which affected the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Since then, the term "Great Salinity Anomaly" has been applied to successive occurrences of the same phenomenon, including the Great Salinity Anomaly of the 1980s and the Great Salinity Anomaly of the 1990s. The Great Salinity Anomalies were advective events, propagating to different sea basins and areas of the North Atlantic, and is on the decadal-scale for the anomalies in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

Harry Leonard Bryden, FRS is an American physical oceanographer, professor at University of Southampton, and staff at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton. He is best known for his work in ocean circulation and in the role of the ocean in the Earth's climate.

The Rapid Climate Change-Meridional Overturning Circulation and Heatflux Array program is a collaborative research project between the National Oceanography Centre, the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (RSMAS), and NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) that measure the meridional overturning circulation (MOC) and ocean heat transport in the North Atlantic Ocean. This array was deployed in March 2004 to continuously monitor the MOC and ocean heat transport that are primarily associated with the Thermohaline Circulation across the basin at 26°N. The RAPID-MOCHA array is planned to be continued through 2014 to provide a decade or longer continuous time series.

Labrador Sea Water is an intermediate water mass characterized by cold water, relatively low salinity compared to other intermediate water masses, and high concentrations of both oxygen and anthropogenic tracers. It is formed by convective processes in the Labrador Sea located between Greenland and the northeast coast of the Labrador Peninsula. Deep convection in the Labrador Sea allows colder water to sink forming this water mass, which is a contributor to the upper layer of North Atlantic Deep Water. North Atlantic Deep Water flowing southward is integral to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. The Labrador Sea experiences a net heat loss to the atmosphere annually.

The cold blob in the North Atlantic describes a cold temperature anomaly of ocean surface waters, affecting the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which is part of the thermohaline circulation, possibly related to global warming-induced melting of the Greenland ice sheet.

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is a large system of ocean currents, like a conveyor belt. It is driven by differences in temperature and salt content and it is an important component of the climate system. However, the AMOC is not a static feature of global circulation. It is sensitive to changes in temperature, salinity and atmospheric forcings. Climate reconstructions from δ18O proxies from Greenland reveal an abrupt transition in global temperature about every 1470 years. These changes may be due to changes in ocean circulation, which suggests that there are two equilibria possible in the AMOC. Stommel made a two-box model in 1961 which showed two different states of the AMOC are possible on a single hemisphere. Stommel’s result with an ocean box model has initiated studies using three dimensional ocean circulation models, confirming the existence of multiple equilibria in the AMOC.

Eddy saturation and eddy compensation are phenomena found in the Southern Ocean. Both are limiting processes where eddy activity increases due to the momentum of strong westerlies, and hence do not enhance their respective mean currents. Where eddy saturations impacts the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), eddy compensation influences the associated Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC).

Rong Zhang is a Chinese-American physicist and climate scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Her research considers the impact of Atlantic meridional overturning circulation on climate phenomena. She was elected Fellow of the American Meteorological Society in 2018 and appointed their Bernhard Haurwitz Memorial Lecturer in 2020.

Cold and dense water from the Nordic Seas is transported southwards as Faroe-Bank Channel overflow. This water flows from the Arctic Ocean into the North Atlantic through the Faroe-Bank Channel between the Faroe Islands and Scotland. The overflow transport is estimated to contribute to one-third of the total overflow over the Greenland-Scotland Ridge. The remaining two-third of overflow water passes through Denmark Strait, the Wyville Thomson Ridge (0.3 Sv), and the Iceland-Faroe Ridge (1.1 Sv).

The Agulhas Leakage is an inflow of anomalously warm and saline water from the Indian Ocean into the South Atlantic due to the limited latitudinal extent of the African continent compared to the southern extension of the subtropical super gyre in the Indian Ocean. The process occurs during the retroflection of the Agulhas Current via shedding of anticyclonic Agulhas Rings, cyclonic eddies and direct inflow. The leakage contributes to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) by supplying its upper limb, which has direct climate implications.