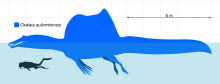

Spinosaurus is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa during the Cenomanian to upper Turonian stages of the Late Cretaceous period, about 100 to 93.5 million years ago. The genus was known first from Egyptian remains discovered in 1912 and described by German palaeontologist Ernst Stromer in 1915. The original remains were destroyed in World War II, but additional material came to light in the early 21st century. It is unclear whether one or two species are represented in the fossils reported in the scientific literature. The best known species is S. aegyptiacus from Egypt, although a potential second species, S. maroccanus, has been recovered from Morocco. The contemporary spinosaurid genus Sigilmassasaurus has also been synonymized by some authors with S. aegyptiacus, though other researchers propose it to be a distinct taxon. Another possible junior synonym is Oxalaia from the Alcântara Formation in Brazil.

Irritator is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what is now Brazil during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous Period, about 113 to 110 million years ago. It is known from a nearly complete skull found in the Romualdo Formation of the Araripe Basin. Fossil dealers had acquired this skull and sold it to the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart. In 1996, the specimen became the holotype of the type species Irritator challengeri. The genus name comes from the word "irritation", reflecting the feelings of paleontologists who found the skull had been heavily damaged and altered by the collectors. The species name is a homage to the fictional character Professor Challenger from Arthur Conan Doyle's novels.

Baryonyx is a genus of theropod dinosaur which lived in the Barremian stage of the Early Cretaceous period, about 130–125 million years ago. The first skeleton was discovered in 1983 in the Smokejack Clay Pit, of Surrey, England, in sediments of the Weald Clay Formation, and became the holotype specimen of Baryonyx walkeri, named by palaeontologists Alan J. Charig and Angela C. Milner in 1986. The generic name, Baryonyx, means "heavy claw" and alludes to the animal's very large claw on the first finger; the specific name, walkeri, refers to its discoverer, amateur fossil collector William J. Walker. The holotype specimen is one of the most complete theropod skeletons from the UK, and its discovery attracted media attention. Specimens later discovered in other parts of the United Kingdom and Iberia have also been assigned to the genus, though many have since been moved to new genera.

Carcharodontosaurus is a genus of carnivorous theropod dinosaur that lived in North Africa from about 100 to 94 million years ago during the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. Two teeth of the genus, now lost, were first described from Algeria by French paleontologists Charles Depéret and Justin Savornin as Megalosaurus saharicus. A partial skeleton was collected by crews of German paleontologist Ernst Stromer during a 1914 expedition to Egypt. Stromer did not report the Egyptian find until 1931, in which he dubbed the novel genus Carcharodontosaurus, making the type species C. saharicus. Unfortunately, this skeleton was destroyed during the Second World War. In 1995 a nearly complete skull of C. saharicus, the first well-preserved specimen to be found in almost a century, was discovered in the Kem Kem Beds of Morocco; it was designated the neotype in 1996. Fossils unearthed from the Echkar Formation of northern Niger were described and named as another species, C. iguidensis, in 2007.

Suchomimus is a genus of spinosaur dinosaur that lived between 125 and 112 million years ago in what is now Niger, north Africa, during the Aptian to early Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous period. It was named and described by paleontologist Paul Sereno and colleagues in 1998, based on a partial skeleton from the Elrhaz Formation. Suchomimus's long and shallow skull, similar to that of a crocodile, earns it its generic name, while the specific name Suchomimus tenerensis alludes to the locality of its first remains, the Ténéré Dese.

Spinosauridae is a clade or family of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs comprising ten to seventeen known genera. Spinosaurid fossils have been recovered worldwide, including Africa, Europe, South America and Asia. Their remains have generally been attributed to the Early to Mid Cretaceous.

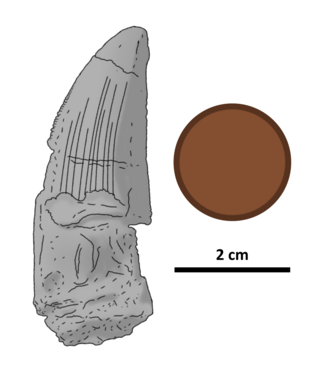

Siamosaurus is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what is now known as China and Thailand during the Early Cretaceous period and is the first reported spinosaurid from Asia. It is confidently known only from tooth fossils; the first were found in the Sao Khua Formation, with more teeth later recovered from the younger Khok Kruat Formation. The only species Siamosaurus suteethorni, whose name honours Thai palaeontologist Varavudh Suteethorn, was formally described in 1986. In 2009, four teeth from China previously attributed to a pliosaur—under the species "Sinopliosaurus" fusuiensis—were identified as those of a spinosaurid, possibly Siamosaurus. It is yet to be determined if two partial spinosaurid skeletons from Thailand and an isolated tooth from Japan also belong to Siamosaurus.

Cristatusaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous Period of what is now Niger, 112 million years ago. It was a baryonychine member of the Spinosauridae, a group of large bipedal carnivores with well-built forelimbs and elongated, crocodile-like skulls. The type species Cristatusaurus lapparenti was named in 1998 by scientists Philippe Taquet and Dale Russell, on the basis of jaw bones and some vertebrae. Two claw fossils were also later assigned to Cristatusaurus. The animal's generic name, which means "crested reptile", alludes to a sagittal crest on top of its snout; while the specific name is in honor of the French paleontologist Albert-Félix de Lapparent. Cristatusaurus is known from the Albian to Aptian Elrhaz Formation, where it would have coexisted with sauropod and iguanodontian dinosaurs, other theropods, and various crocodylomorphs.

Sigilmassasaurus is a controversial genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived approximately 100 to 94 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous Period in what is now northern Africa. Named in 1996 by Canadian paleontologist Dale Russell, it contains a single species, Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis. The identity of the genus has been debated by scientists, with some considering its fossils to represent material from the closely related species Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, while others have classified it as a separate taxon, forming the clade Spinosaurini with Spinosaurus as its sister taxon.

Suchosaurus is a spinosaurid dinosaur from Cretaceous England and Portugal, originally believed to be a genus of crocodile. The type material, consisting of teeth, was used by British palaeontologist Richard Owen to name the species S. cultridens in 1841. Later in 1897, French palaeontologist Henri-Émile Sauvage named a second species, S. girardi, based on two fragments from the mandible and one tooth discovered in Portugal. Suchosaurus is possibly a senior synonym of the contemporary spinosaurid Baryonyx, but is usually considered a dubious name due to the paucity of its remains, and is considered an indeterminate baryonychine. In the Wadhurst Clay Formation of what is now southern England, Suchosaurus lived alongside other dinosaurs, as well as plesiosaurs, mammals, and crocodyliforms.

Xixiasaurus is a genus of troodontid dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous Period in what is now China. The only known specimen was discovered in Xixia County, Henan Province, in central China, and became the holotype of the new genus and species Xixiasaurus henanensis in 2010. The names refer to the areas of discovery, and can be translated as "Henan Xixia lizard". The specimen consists of an almost complete skull, part of the lower jaw, and teeth, as well as a partial right forelimb.

The Alcântara Formation is a geological formation in northeastern Brazil whose strata date back to the Cenomanian of the Late Cretaceous.

Ichthyovenator is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what is now Laos, sometime between 125 and 113 million years ago, during the Aptian stage of the Early Cretaceous period. It is known from fossils collected from the Grès supérieurs Formation of the Savannakhet Basin, the first of which were found in 2010, consisting of a partial skeleton without the skull or limbs. This specimen became the holotype of the new genus and species Ichthyovenator laosensis, and was described by palaeontologist Ronan Allain and colleagues in 2012. The generic name, meaning "fish hunter", refers to its assumed piscivorous lifestyle, while the specific name alludes to the country of Laos. In 2014, it was announced that more remains from the dig site had been recovered; these fossils included teeth, more vertebrae (backbones) and a pubic bone from the same individual.

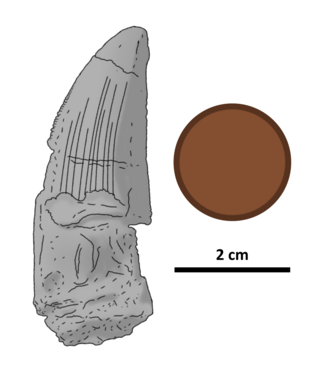

Ostafrikasaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period of what is now Lindi Region, Tanzania. It is known only from fossil teeth discovered sometime between 1909 and 1912, during an expedition to the Tendaguru Formation by the Natural History Museum of Berlin. Eight teeth were originally attributed to the dubious dinosaur genus Labrosaurus, and later to Ceratosaurus, both known from the North American Morrison Formation. Subsequent studies attributed two of these teeth to a spinosaurid dinosaur, and in 2012, Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus was named by French palaeontologist Eric Buffetaut, with one tooth as the holotype, and the other referred to the same species. The generic name comes from the German word for German East Africa, the former name of the colony in which the fossils were found, while the specific name comes from the Latin words for "thick" and "serrated", in reference to the form of the animal's teeth.

Camarillasaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous period (Barremian) of Camarillas, Teruel Province, in what is now northeastern Spain. Described in 2014, it was originally identified as a ceratosaurian theropod, but later studies suggested affinities to the Spinosauridae. If it does represent a spinosaur, Camarillasaurus would be one of five spinosaurid taxa known from the Iberian peninsula, the others being Iberospinus, Protathlitis, Riojavenatrix, and Vallibonavenatrix.

Atlanticopristis is an extinct genus of sclerorhynchid that lived during the Middle Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of what is now the Northeast Region of Brazil, between 100.5 and 93.9 million years ago. Fourteen fossil teeth from Atlanticopristis were found in the Alcântara Formation, and referred to the closely related Onchopristis in 2007; a redescription in 2008 by Brazilian paleontologists Manuel Medeiros and Agostinha Pereira assigned it to a new genus containing one species, Atlanticopristis equatorialis.

Vallibonavenatrix is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) Arcillas de Morella Formation of Castellón, Spain. The type and only species is Vallibonavenatrix cani, known from a partial skeleton.

Ceratosuchops is a genus of spinosaurid from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) of Britain.

Riparovenator is a genus of baryonychine spinosaurid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) period of Britain. The genus contains a single species, Riparovenator milnerae.

Baryonychinae is an extinct clade or subfamily of spinosaurids from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian-Albian) of Britain, Portugal, and Niger. The clade was named by Charig & Milner in 1986 and defined by Sereno et al. in 1998 and Holtz et al. in 2004 as all taxa more closely related to Baryonyx walkeri than to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.