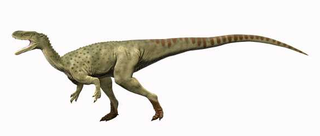

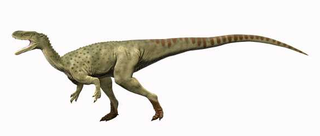

Megalosaurus is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic Epoch of southern England. Although fossils from other areas have been assigned to the genus, the only certain remains of Megalosaurus come from Oxfordshire and date to the late Middle Jurassic.

Ceratosaurus was a carnivorous theropod dinosaur that lived in the Late Jurassic period. The genus was first described in 1884 by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh based on a nearly complete skeleton discovered in Garden Park, Colorado, in rocks belonging to the Morrison Formation. The type species is Ceratosaurus nasicornis.

Afrovenator is a genus of megalosaurid theropod dinosaur from the Middle or Late Jurassic Period on the Tiourarén Formation and maybe the Irhazer II Formation of the Niger Sahara region in northern Africa. Afrovenator represents the only properly identified Gondwanan megalosaur, with proposed material of the group present in the Late Jurassic on Tacuarembó Formation of Uruguay and the Tendaguru Formation of Tanzania.

Cetiosauriscus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived between 166 and 164 million years ago during the Callovian in what is now England. A herbivore, Cetiosauriscus had — by sauropod standards — a moderately long tail, and longer forelimbs, making them as long as its hindlimbs. It has been estimated as about 15 m (49 ft) long and between 4 and 10 t in weight.

Megalosauridae is a monophyletic family of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs within the group Megalosauroidea. Appearing in the Middle Jurassic, megalosaurids were among the first major radiation of large theropod dinosaurs. They were a relatively primitive group of basal tetanurans containing two main subfamilies, Megalosaurinae and Afrovenatorinae, along with the basal genus Eustreptospondylus, an unresolved taxon which differs from both subfamilies.

Elaphrosaurus is a genus of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 154 to 150 million years ago during the Late Jurassic Period in what is now Tanzania in Africa. Elaphrosaurus was a medium-sized but lightly built member of the group that could grow up to 6.2 m (20 ft) long. Morphologically, this dinosaur is significant in two ways. Firstly, it has a relatively long body but is very shallow-chested for a theropod of its size. Secondly, it has very short hindlimbs in comparison with its body. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that this genus is likely a ceratosaur. Earlier suggestions that it is a late surviving coelophysoid have been examined but generally dismissed. Elaphrosaurus is currently believed to be a very close relative of Limusaurus, an unusual beaked ceratosaurian which may have been either herbivorous or omnivorous.

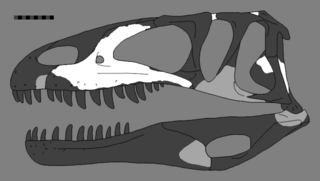

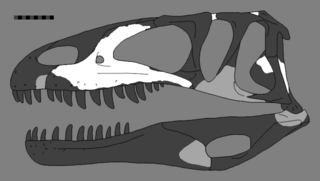

Monolophosaurus is an extinct genus of tetanuran theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic Shishugou Formation in what is now Xinjiang, China. It was named for the single crest on top of its skull. Monolophosaurus was a mid-sized theropod at about 5–5.5 metres (16–18 ft) long and weighed 475 kilograms (1,047 lb).

Megalosauroidea is a superfamily of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs that lived from the Middle Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous period. The group is defined as Megalosaurus bucklandii and all taxa sharing a more recent common ancestor with it than with Allosaurus fragilis or Passer domesticus. Members of the group include Spinosaurus, Megalosaurus, and Torvosaurus. They are possibly paraphyletic in nature with respect to Allosauroidea.

Magnosaurus was a genus of theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of England. It is based on fragmentary remains and has often been confused with or included in Megalosaurus.

Chuandongocoelurus is a genus of carnivorous tetanuran theropod dinosaur from the Jurassic of China.

Dubreuillosaurus is a genus of carnivorous dinosaur from the middle Jurassic Period. It is a megalosaurid theropod. Its fossils were found in France. The only named species, Dubreuillosaurus valesdunensis, was originally described as a species of Poekilopleuron, Poekilopleuron? valesdunensis, which is still formally the type species of the genus. It was later renamed Dubreuillosaurus valesdunensis when, in 2005, Allain came to the conclusion that it was not part of the genus Poekilopleuron. Its type specimen, MNHN 1998-13, is only rivalled in the number of preserved elements in this group by that of Eustreptospondylus. Dubreuillosaurus is considered to be the sister species of Magnosaurus. It did not show signs of insular dwarfism even though it was uncovered on an island.

Marshosaurus is a genus of medium-sized carnivorous theropod dinosaur, belonging to the Megalosauroidea, from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of Utah and possibly Colorado.

Piveteausaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur known from a partial skull discovered in the Middle Jurassic Marnes de Dives formation of Calvados, in northern France and lived about 164.7-161.2 million years ago. In 2012 Thomas Holtz gave a possible length of 11 meters.

Streptospondylus is a genus of tetanuran theropod dinosaur known from the Late Jurassic period of France, 161 million years ago. It was a medium-sized predator with an estimated length of 6 meters (19.5 ft) and a weight of 500 kg (1,100 lbs).

Spinostropheus is a genus of carnivorous neotheropod theropod dinosaur that lived in the Middle Jurassic period and has been found in the Tiouraren Formation, Niger. The type and only species is S. gautieri.

Poekilopleuron is a genus of tetanuran dinosaur, which lived during the middle Bathonian of the Jurassic, about 168 to 166 million years ago. The genus has been used under many different spelling variants, although only one, Poekilopleuron, is valid. The type species is P. bucklandii, named after William Buckland, and many junior synonyms of it have also been erected. Little material is currently known, as the holotype was destroyed in World War II, although many casts of the material still exist.

Noasauridae is an extinct family of theropod dinosaurs belonging to the group Ceratosauria. They were closely related to the short-armed abelisaurids, although most noasaurids had much more traditional body types generally similar to other theropods. Their heads, on the other hand, had unusual adaptations depending on the subfamily. 'Traditional' noasaurids, sometimes grouped in the subfamily Noasaurinae, had sharp teeth which splayed outwards from a downturned lower jaw.

Lophostropheus is an extinct genus of coelophysoid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 205.6 to 196.5 million years ago during the boundary between the Late Triassic Period and the Early Jurassic Period, in what is now Normandy, France. Lophostropheus is one of the few dinosaurs that may have survived the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event.

Duriavenator is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in what is now England during the Middle Jurassic, about 168 million years ago. In 1882, upper and lower jaw bones of a dinosaur were collected near Sherborne in Dorset, and Richard Owen considered the fossils to belong to the species Megalosaurus bucklandii, the first named non-bird dinosaur. By 1964, the specimen was recognised as belonging to a different species, and in 1974 it was described as a new species of Megalosaurus, M. hesperis; the specific name means 'the West' or 'western'. Later researchers questioned whether the species belonged to Megalosaurus, in which many fragmentary theropods from around the world had historically been placed. After examining the taxonomic issues surrounding Megalosaurus, Roger B. J. Benson moved M. hesperis to its own genus in 2008, Duriavenator; this name means "Dorset hunter".

Leshansaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Shaximiao Formation of what is now China. It was described in 2009 by a team of Chinese paleontologists. The type species is Leshansaurus qianweiensis. Fossils of Leshansaurus were discovered in strata from the Shangshaximiao Formation, a formation rich in dinosaur fossils. Li et al. referred this taxon to Sinraptoridae – a group of carnosaurian theropods, but it may belong to Megalosauridae instead.