Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Confucianism developed from teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE), during a time that was later referred to as the Hundred Schools of Thought era. Confucius considered himself a transmitter of cultural values inherited from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Western Zhou (c. 1046–771 BCE) dynasties. Confucianism was suppressed during the Legalist and autocratic Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), but survived. During the Han dynasty, Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang–Lao as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behavior, whereas in others, they are ignored and suppressed. They differ from broader notions of human rights through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls, in favor of men and boys.

Mencius was a Chinese Confucian philosopher, often described as the Second Sage (亞聖) to reflect his traditional esteem relative to Confucius himself. He was part of Confucius's fourth generation of disciples, inheriting his ideology and developing it further. Living during the Warring States period, he is said to have spent much of his life travelling around the states offering counsel to different rulers. Conversations with these rulers form the basis of the Mencius, which would later be canonised as a Confucian classic.

The snake is the sixth of the twelve-year cycle of animals which appear in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar. The Year of the Snake is associated with the Earthly Branch symbol 巳.

Generation name is one of the characters in a traditional Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean given name, and is so called because each member of a generation share that character.

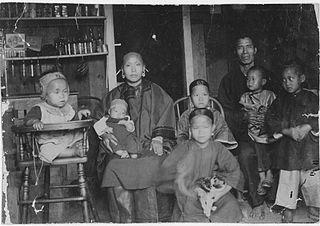

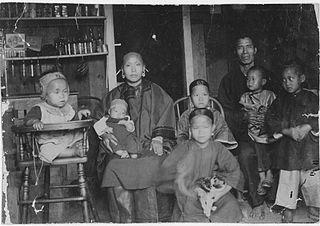

Traditional Chinese marriage is a ceremonial ritual within Chinese societies that involves not only a union between spouses but also a union between the two families of a man and a woman, sometimes established by pre-arrangement between families. Marriage and family are inextricably linked, which involves the interests of both families. Within Chinese culture, romantic love and monogamy were the norm for most citizens. Around the end of primitive society, traditional Chinese marriage rituals were formed, with deer skin betrothal in the Fuxi era, the appearance of the "meeting hall" during the Xia and Shang dynasties, and then in the Zhou dynasty, a complete set of marriage etiquette gradually formed. The richness of this series of rituals proves the importance the ancients attached to marriage. In addition to the unique nature of the "three letters and six rituals", monogamy, remarriage and divorce in traditional Chinese marriage culture are also distinctive.

Women's health in China refers to the health of women in People's Republic of China (PRC), which is different from men's health in China in many ways. Health, in general, is defined in the World Health Organization (WHO) constitution as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity". The circumstance of Chinese women's health is highly contingent upon China's historical contexts and economic development during the past seven decades. A historical perspective on women's health in China entails examining the healthcare policies and its outcomes for women in the pre-reform period (1949-1978) and the post-reform period since 1978.

The All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) is a women's rights people's organization established in China on 24 March 1949. It was originally called the All-China Democratic Women's Foundation, and was renamed the All-China Women's Federation in 1957. It has acted as the official leader of the women's movement in China since its founding. It is responsible for promoting government policies on women, and protecting women's rights within the government, while liberating them from traditional norms within society and involving them in social revolution with the aim to promote their overall status and welfare in Chinese society. As a united political community, women in the ACWF achieved political momentum, power among the male elite, and required representation.

The Chinese kinship system is among the most complicated of all the world's kinship systems. It maintains a specific designation for almost every member's kin based on their generation, lineage, relative age, and gender. The traditional system was agnatic, based on patriarchal power, patrilocal residence, and descent through the male line. Although there has been much change in China over the last century, especially after 1949, there has also been substantial continuity.

Women in China make up approximately 49% of the population. In modern China, the lives of women have changed significantly due to the late Qing dynasty reforms, the changes of the Republican period, the Chinese Civil War, and the rise of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Like women in many other cultures, women in China have been historically oppressed. For thousands of years, women in China lived under the patriarchal social order characterized by the Confucius teaching of "filial piety".

This is a list of topics related to the issue of masculism, men's liberation, the men's movement, and men's rights:

Patriarchy is a social system in which men typically hold authority and privilege. In anthropology, it refers to a family or clan structure where the father or eldest male holds supremacy within the family, while in feminist theory, it encompasses a broader social structure where men collectively dominate societal norms and institutions.

Bama Yao Autonomous County is a county in Guangxi, China. It is under the administration of Hechi City. The residents of Bama County have a reputation for longevity, and Bama has been the focus of studies from geriatricians nationwide.

Biblical patriarchy, also known as Christian patriarchy, is a set of beliefs in Evangelical Protestant Christianity concerning gender relations and their manifestations in institutions, including marriage, the family, and the home. It sees the father as the head of the home, responsible for the conduct of his family. Notable people associated with biblical patriarchy include Douglas Wilson, R. C. Sproul, Jr., Voddie Baucham, the Duggar family, Dale Partridge, and Douglas Phillips.

The status of women in Taiwan has been based on and affected by the traditional patriarchal views and social structure within Taiwanese society, which put women in a subordinate position to men, although the legal status of Taiwanese women has improved in recent years, particularly during the past three decades when the family law underwent several amendments. Throughout history, women in Taiwan had suffered various forms of discrimination, including foot binding.

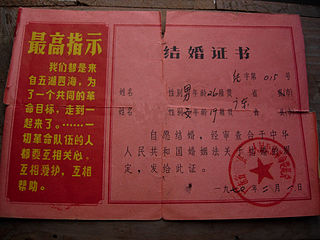

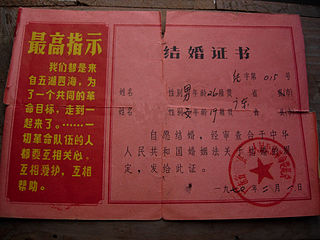

The New Marriage Law was a civil marriage law passed in the People's Republic of China on May 1, 1950. It was a radical change from existing patriarchal Chinese marriage customs, and needed constant support from propaganda campaigns. It has since been superseded by the Second Marriage Law of 1980. It was formally repealed by the Civil Code in 2021.

Women in ancient and imperial China were restricted from participating in various realms of social life, through social stipulations that they remain indoors, whilst outside business should be conducted by men. The strict division of the sexes, apparent in the policy that "men plow, women weave", partitioned male and female histories as early as the Zhou dynasty, with the Rites of Zhou, even stipulating that women be educated specifically in "women's rites". Though limited by policies that prevented them from owning property, taking examinations, or holding office, their restriction to a distinctive women's world prompted the development of female-specific occupations, exclusive literary circles, whilst also investing certain women with certain types of political influence inaccessible to men.

In 2021, China ranked 48th out of 191 countries on the United Nations Development Programme's Gender Inequality Index (GII). Among the GII components, China's maternal mortality ratio was 32 out of 100,000 live births. In education 58.7 percent of women age 25 and older had completed secondary education, while the counterpart statistic for men was 71.9 percent. Women's labour power participation rate was 63.9 percent, and women held 23.6 percent of seats in the National People's Congress. In 2019, China ranked 39 out of the 162 countries surveyed during the year.

Sheng nü, translated as 'leftover women' or 'leftover ladies', are women who remain unmarried in their late twenties and beyond in China. The term was popularized by the All-China Women's Federation. Most prominently used in China, the term has also been used colloquially to refer to women in India, North America, Europe, and other parts of Asia. The term compares unmarried women to leftover food and has gone on to become widely used in the mainstream media and has been the subject of several television series, magazine and newspaper articles, and book publications, focusing on the negative connotations and positive reclamation of the term. While initially backed and disseminated by pro-government media in 2007, the term eventually came under criticism from government-published newspapers two years later. Xu Xiaomin of The China Daily described the sheng nus as "a social force to be reckoned with" and others have argued the term should be taken as a positive to mean "successful women". The slang term, 3S or 3S Women, meaning "single, seventies (1970s), and stuck" has also been used in place of sheng nu.

Postpartum confinement is a traditional practice following childbirth. Those who follow these customs typically begin immediately after the birth, and the seclusion or special treatment lasts for a culturally variable length: typically for one month or 30 days, 26 days, up to 40 days, two months, or 100 days. This postnatal recuperation can include care practices in regards of "traditional health beliefs, taboos, rituals, and proscriptions." The practice used to be known as "lying-in", which, as the term suggests, centres on bed rest. In some cultures, it may be connected to taboos concerning impurity after childbirth.