The General Strike of 1910 was a labor strike by trolley workers of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company that grew to a citywide riot and general strike in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. [2] [3] [1]

The General Strike of 1910 was a labor strike by trolley workers of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company that grew to a citywide riot and general strike in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. [2] [3] [1]

On May 29, 1909, a committee of the local AFL affiliate Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America approached officials of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT) with demands for an hourly wage of 25 cents for motormen and conductors, the right to buy their uniforms on the open market, limits of workdays to 9 or 10 hours and recognition of the Association. Officials at PRT refused to meet with the committee, triggering a strike. [4] : p143

PRT responded by bringing in strike breakers from New York City and Boston, notably strikebreakers working for Pearl Bergoff near the beginning of his career as "King of the Strikebreakers". [5] Violence broke out, with trolley cars, tracks and wiring destroyed, police brutality and wholesale arrests of strikers. Given the population's general dislike of the company for poor service, mismanagement and backroom political dealings, the union felt safe issuing an ultimatum. John J. Murphy of the Central Labor Union issued the terms:

If the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company does not meet the demands of the trolley workers by Thursday night (June 7), a strike of all organized labor bodies of Philadelphia affiliated with the Central Labor Union, representing 75,000 men, will be called for Friday morning. The present strike is only a beginning of the fight which will be waged by organized labor to emancipate the city of Philadelphia from the thraldom of capitalism. [4] : p144

State Senator James P. McNichol met with the union and Mayor Reyburn urged PRT to settle. On June 2, 1909, an agreement was announced. The workers received a wage increase from 21 to 22 cents per hour, a ten-hour work day, the right to buy uniforms from five clothiers and recognition of the union. The company, however, soon ignored one of the key terms of the deal by establishing a replacement union, refusing to meet with representatives of Amalgamated and giving choice jobs and promotions to members of PRT's union. [4] : p144

In December 1909 the Amalgamated union made new demands for a wage increase to 25 cents an hour. PRT flatly refused and on January 1, 1910, without union discussion, announced a complicated "welfare plan" for the workers; keeping the 22 cents an hour pay rate and adding insurance and pension provisions. Two days later, the company fired seven workers for announcing they were joining Amalgamated and denouncing the welfare provisions as the company's attempt to undermine union demands. Amalgamated requested arbitration, which the company refused. A strike vote was called. With over 5,300 votes cast, the strike was approved with less than 5% voting against. The strike resolution charged PRT with creating "dissention and discord" by forming the company-controlled union, favoring employees antagonistic to Amalgamated, refusing to address grievances, attempting to prevent workers from joining Amalgamated, firing workers who joined and refusing arbitration. The resolution left the timing of the actual strike to Amalgamated's executive board. Local newspapers, citing the near unanimity of the vote and the union's obvious strength, urged PRT to give the situation urgent attention. PRT issued a statement saying "The strike vote will not change the attitude of the company the slightest." Mayor Reyburn endorsed the company's position, calling the union members "semi-public functionaries" who owe their service to the city. [4] : p145

Negotiations slowly got under way and labored on until mid-February. AFL President Samuel Gompers urged PRT to join the union in arbitration to reach a settlement. PRT dismissed the offer saying they had the situation under control and stating they intended to uphold the rights of workers to join or not join a union of their choosing and breaking off negotiations. On February 19, 1910, PRT fired 173 workers, all of them members of the union, "for the good of the service" and hired replacement workers from New York City. [4] : p146 Immediately after the firings, the union leadership ordered the strike, taking their respective trolley cars off the streets effective at 1:00 that afternoon.

This section needs expansionwith: Timeline of strike unclear. You can help by adding to it. (June 2023) |

On the first day of the strike, Mayor Reyburn dispatched heavy police guard to the trolley barns. The union claimed 6,200 of the PRT's 7,000 employees walked out. PRT claimed 3,000 workers remained on the job. [2]

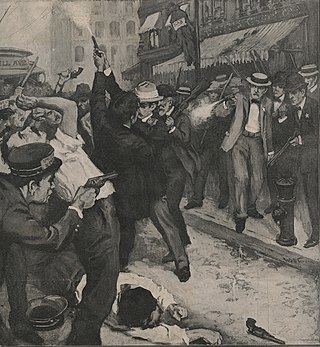

It was reported worldwide that one volunteer motorman, "driving his car full-speed through the crowd with one hand on the controller and the other holding a revolver, was dragged from the platform when the car had been wrecked by a spiked switch, and killed". [6]

Mobs pulled down the masonry of a school being built at 9th and Mifflin streets (Southwark School), using the stones to block the tracks and build makeshift bunkers. As a trolley with police guards approached, the crowd of 1,500 cheered, then smashed the car with rocks and clubs. Both police officers were knocked unconscious and an eight-year-old boy suffered a fatal blow to the head. Similar events occurred throughout the city, with tracks, lines and trolley cars destroyed. [2]

At Smith's Hall, police commandeered heavy equipment to force their way in while the mob showered them with rocks, bricks and tools from a second-story window. When the battle was over, 12 were arrested and 20 people were hospitalized. [2]

A crowd of 2,000 seized a trolley that was blocked by several other cars they had destroyed. After the crew and police were driven off, the trolley was doused with fuel and set on fire. Meanwhile, a crowd of 5,000 had blockaded tracks in Center City. When a trolley approached the crew was seized, dragged into the street and beaten while the police watched helplessly. While one officer attempted to back the trolley out, the other fired warning shots into the air. The mob responded with a massive barrage of bricks and stones and the police fired randomly into the crowd. A bomb threat in Germantown was disregarded until dynamite was loaded onto the tracks by a mob of 2,000. [2] In Kensington, Richmond and South Philadelphia, the mayor ordered police to act under provisions of the Riot Act. [2] The mayor called for 3,000 citizens to serve police duty. [2] Amalgamated offered 6,000 union men -- "bonafide citizens of Philadelphia (to) preserve peace and order"—an offer the mayor rejected. [4] By 6 p.m. the next day, PRT had ordered all trolleys off the streets while promising service would be restored the following morning. [2]

In stark contrast to the chaos throughout the city, the union leaders enjoyed a sort of victory parade, taxied through cheering crowds to a series of speeches at several locations. [2]

With the union threatening a general strike to hobble the city if strike breakers were brought in, PRT brought in 600 strike breakers, while denying they had done so. [2] [4] Trolley workers in Trenton, sensing the moment, went on strike, shutting their transit company down with a strike that would later fuel the rise of the Central Labor Union. [7]

The final straw for calling a general strike was the National Guard and the Pennsylvania Constabulary entering the city to provide protection for PRT's few remaining workers. Members of other unions throughout the city saw this as a clear signal that the city and state governments were uniting in favor of the companies against the unions. [4] [7] When the well-trained, heavily armed Constabulary failed to immediately restore order, there was talk of bringing in the United States Army or Navy. [8]

With the general population, newspapers, retailers and religious groups uniting against PRT, a general strike was called. All unions in all industries were asked to walk out, in hopes of adding financial burden to the city and PRT. [9]

As city commerce ground to a near halt, the general strike had wider impacts, leading to sympathy walkouts along the East Coast. The public was hungry for reform and vengeance on the hated industries who controlled transportation. [9]

The union's "scorched earth, take no prisoners" approach eventually brought PRT to the negotiating table, ending the general strike while the trolley walk-out continued. [9]

In the face of a prolonged strike, PRT held to the common belief that workers could, in effect, be starved back to work. [7] By the end of March, the general strike was called off. The wives, daughters and women friends of the striking car men set about organizing a woman's auxiliary of the car men's union to raise funds in support of the strike. The city's Director of Public Safety turned down their requests for parade permits. During the court hearing seeking to overturn the ruling, the auxiliary's organizer, when questioned about her politics, stated that she was not an anarchist, but a Socialist. She stated that there would be men in the parade, but only to hold babies and push strollers so that the women marchers would have their hands free to collect donations. The court ruled against the auxiliary and the refusal to issue the permit was not overturned. [4]

The women's auxiliary went on to raise funds through a variety of sales, entertainment events and door-to-door solicitions, allowing the strikers to continue far longer than they could have afforded to otherwise. [4]

The trolley workers' strike presented a template for further action and served to empower similar unions to take to the streets. Eventually, the disgruntled riders managed to freeze trolley fares at 5 cents well beyond the fiscal pressures of most traction companies, ironically leading to severely under-funded transit systems and bankrupt rail lines. [9]

Transport Workers Union of America (TWU) is a United States labor union that was founded in 1934 by subway workers in New York City, then expanded to represent transit employees in other cities, primarily in the eastern U.S. This article discusses the parent union and its largest local, Local 100, which represents the transport workers of New York City. TWU is a member of the AFL–CIO.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was the first strike that spread across multiple states in the U.S. The strike finally ended 52 days later, after it was put down by unofficial militias, the National Guard, and federal troops. Because of economic problems and pressure on wages by the railroads, workers in numerous other states, from New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland, into Illinois and Missouri, also went out on strike. An estimated 100 people were killed in the unrest across the country. In Martinsburg, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and other cities, workers burned down and destroyed both physical facilities and the rolling stock of the railroads—engines and railroad cars. Some locals feared that workers were rising in revolution, similar to the Paris Commune of 1871, while others joined their efforts against the railroads.

The Toledo Auto-Lite strike was a strike by a federal labor union of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) against the Electric Auto-Lite company of Toledo, Ohio, from April 12 to June 3, 1934.

The Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) was the main public transit operator in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1940 to 1968. A private company, PTC was the successor to the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT), in operation since 1902, and was the immediate predecessor of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA).

The Indianapolis streetcar strike of 1913 and the subsequent police mutiny and riots was a civil conflict in Indianapolis, Indiana. The events began as a workers strike by the union employees of the Indianapolis Traction & Terminal Company and their allies on Halloween night, October 31, 1913. The company was responsible for public transportation in Indianapolis, the capital city and transportation hub of the U.S. state of Indiana. The unionization effort was being organized by the Amalgamated Street Railway Employees of America who had successfully enforced strikes in other major United States cities. Company management suppressed the initial attempt by some of its employees to unionize and rejected an offer of mediation by the United States Department of Labor, which led to a rapid rise in tensions, and ultimately the strike. Government response to the strike was politically charged, as the strike began during the week leading up to public elections. The strike effectively shut down mass transit in the city and caused severe interruptions of statewide rail transportation and the 1913 city elections.

The Philadelphia transit strike of 1944 was a sickout strike by white transit workers in Philadelphia that lasted from August 1 to August 6, 1944. The strike was triggered by the decision of the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC), made under prolonged pressure from the federal government in view of significant wartime labor shortages, to allow black employees of the PTC to hold non-menial jobs, such as motormen and conductors, that were previously reserved for white workers only. On August 1, 1944, the eight black employees being trained as streetcar motormen were due to make their first trial run. That caused the white PTC workers to start a massive sickout strike.

The St. Louis streetcar strike of 1900 was a labor action, and resulting civil disruption, against the St. Louis Transit Company by a group of three thousand workers unionized by the Amalgamated Street Railway Employees of America.

From 1895 to 1929, streetcar strikes affected almost every major city in the United States. Sometimes lasting only a few days, these strikes were often "marked by almost continuous and often spectacular violent conflict," at times amounting to prolonged riots and weeks of civil insurrection.

William Daniel Mahon (1861–1949) was a former coal miner and streetcar driver who became president of the Amalgamated Association of Street Railway Employees of America, now the Amalgamated Transit Union.

The 1877 St. Louis general strike was one of the first general strikes in the United States. It grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party, the main radical political party of the era.

The Los Angeles streetcar strike of 1919 was the most violent revolt against the open-shop policies of the Pacific Electric Railway Company in Los Angeles. Labor organizers had fought for over a decade to increase wages, decrease work hours, and legalize unions for streetcar workers of the Los Angeles basin. After having been denied unionization rights and changes in work policies by the National War Labor Board, streetcar workers broke out in massive protest before being subdued by local armed police force.

The Denver streetcar strike of 1920 was a labor action and series of urban riots in downtown Denver, Colorado, beginning on August 1, 1920, and lasting six days. Seven were killed and 50 were seriously injured in clashes among striking streetcar workers, strike-breakers, local police, federal troops and the public. This was the "largest and most violent labor dispute involving transportation workers and federal troops".

The Scranton general strike was a widespread work stoppage in 1877 by workers in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which took place as part of the Great Railroad Strike, and was the last in a number of violent outbreaks across Pennsylvania. The strike began on July 23 when railroad workers walked off the job in protest of recent wage cuts, and within three days it grew to include perhaps thousands of workers from a variety of industries.

The Saint John street railway strike of 1914 was a strike by workers on the street railway system in Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada, which lasted from 22–24 July 1914, with rioting by Saint John inhabitants occurring on 23 and 24 July. The strike shattered the image of Saint John as a conservative town dominated primarily by ethnic and religious divisions, and highlighting tensions between railway industrialists and the local working population.

The Pittsburgh railway strike occurred in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. It was one of many incidents of strikes, labor unrest and violence in cities across the United States, including several in Pennsylvania. Other cities dealing with similar unrest included Philadelphia, Reading, Shamokin and Scranton. The incidents followed repeated reductions in wages and sometimes increases in workload by railroad companies, during a period of economic recession following the Panic of 1873.

The Atlanta streetcar strike of 1916 was a labor strike involving streetcar operators for the Georgia Railway and Power Company in Atlanta, Georgia. Precipitated by previous strike action by linemen of Georgia Railway earlier that year, the strike began on September 30 and ended January 5 of the following year. The main goals of the strike included increased pay, shorter working hours, and union recognition. The strike ended with the operators receiving a wage increase, and subsequent strike action the following year lead to union recognition.

The 1910 streetcar strike was a union protest against labor practices by the Columbus Railway and Light Co. in Columbus, Ohio in 1910. The summertime strike began as peaceful protests, but led to thousands rioting throughout the city, injuring hundreds of people.

The 1911 Grand Rapids furniture workers' strike was a general strike performed by furniture workers in Grand Rapids, which was then a national leader of furniture production.

The 1917 Twin Cities streetcar strike was a labor strike involving streetcar workers for the Twin City Rapid Transit Company (TCRT) in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area of the U.S. state of Minnesota, popularly known as the Twin Cities. The initial strike lasted from October 6 to 9, 1917, though the broader labor dispute between the streetcar workers and the company lasted for several months afterwards and included a lockout, a sympathetic general strike, and months of litigation before ending in failure for the strikers.

The 1916–1917 Springfield streetcar strike was a strike among streetcar workers in and around Springfield, Missouri. The strike went from October 5, 1916 to June 16, 1917 caused by the streetcar company's refusal to recognize the union. As a result, the union was recognized after 8 months of striking.