Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the labour movement that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes, with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of production and the economy at large through social ownership. Developed in French labor unions during the late 19th century, syndicalist movements were most predominant amongst the socialist movement during the interwar period that preceded the outbreak of World War II.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.

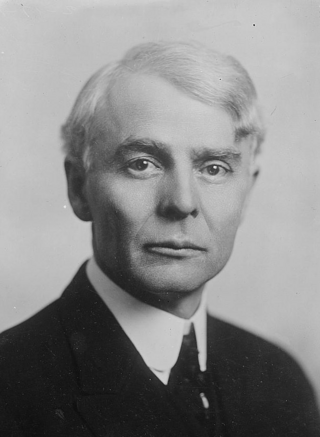

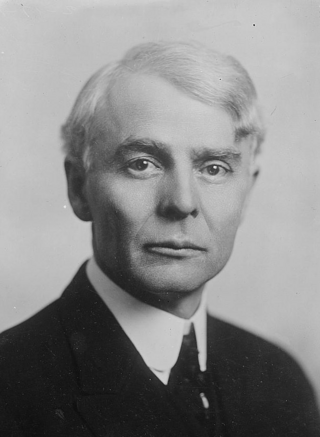

William Dudley Haywood, nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of America. During the first two decades of the 20th century, Haywood was involved in several important labor battles, including the Colorado Labor Wars, the Lawrence Textile Strike, and other textile strikes in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

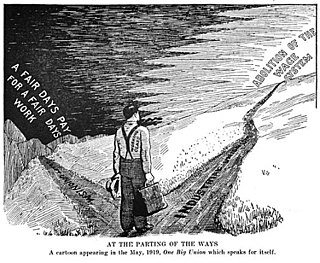

The One Big Union is an idea originating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries amongst trade unionists to unite the interests of workers and offer solutions to all labour problems.

The International Workers' Association – Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA–AIT) is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions and initiatives.

The first Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the Russian 1917 October Revolution, German Revolution of 1918–1919, and anarchist bombings in the U.S. At its height in 1919–1920, concerns over the effects of radical political agitation in American society and the alleged spread of socialism, communism, and anarchism in the American labor movement fueled a general sense of concern.

The Centralia Tragedy, also known as the Centralia Conspiracy and the Armistice Day Riot, was a violent and bloody incident that occurred in Centralia, Washington, on November 11, 1919, during a parade celebrating the first anniversary of Armistice Day. The conflict between the American Legion and Industrial Workers of the World members resulted in six deaths, others being wounded, multiple prison terms, and an ongoing and especially bitter dispute over the motivations and events that precipitated the event. Both Centralia and the neighboring town of Chehalis had a large number of World War I veterans, with robust chapters of the Legion and many IWW members, some of whom were also war veterans.

The history of the socialist movement in the United States spans a variety of tendencies, including anarchists, communists, democratic socialists, social democrats, Marxists, Marxist–Leninists, Trotskyists and utopian socialists. It began with utopian communities in the early 19th century such as the Shakers, the activist visionary Josiah Warren and intentional communities inspired by Charles Fourier. Labor activists, usually Jewish, German, or Finnish immigrants, founded the Socialist Labor Party of America in 1877. The Socialist Party of America was established in 1901. By that time, anarchism also rose to prominence around the country. Socialists of different tendencies were involved in early American labor organizations and struggles. These reached a high point in the Haymarket massacre in Chicago, which founded the International Workers' Day as the main labour holiday around the world, Labor Day and making the eight-hour day a worldwide objective by workers organizations and socialist parties worldwide.

The Boston police strike occurred on September 9, 1919, when Boston police officers went on strike seeking recognition for their trade union and improvements in wages and working conditions. Police Commissioner Edwin Upton Curtis denied that police officers had any right to form a union, much less one affiliated with a larger organization like the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which some attribute to concerns that unionized police would not protect the interest of city officials and business leaders. Attempts at reconciliation between the Commissioner and the police officers, particularly on the part of Boston's Mayor Andrew James Peters, failed.

The Red International of Labor Unions, commonly known as the Profintern, was an international body established by the Communist International (Comintern) with the aim of coordinating communist activities within trade unions. Formally established in 1921, the Profintern aimed to act as a counterweight to the influence of the so-called "Amsterdam International", the social-democratic International Federation of Trade Unions, an organization which the Comintern branded as "class-collaborationist" and as an impediment to revolution. After entering a period of decline in the middle 1930s, the Profintern was finally dissolved in 1937 with the advent of Comintern's "Popular Front" policy.

Joseph James "Smiling Joe" Ettor (1885–1948) was an Italian-American trade union organizer who, in the middle-1910s, was one of the leading public faces of the Industrial Workers of the World. Ettor is best remembered as a defendant in a controversial trial related to a killing in the seminal Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912, in which he was acquitted of charges of having been an accessory.

Ole Thorsteinsson Hanson was an American politician who served as mayor of Seattle, Washington, from 1918 to 1919. Hanson became a national figure promoting law and order when he took a hardline position during the 1919 Seattle General Strike. He then resigned as mayor, wrote a book, and toured the lecture circuit, earning tens of thousands of dollars in honoraria lecturing to conservative civic groups about his experiences and views, promoting opposition to labor unions and Bolshevism. Hanson later left Washington and founded the city of San Clemente, California, in 1925.

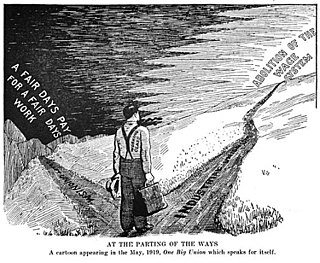

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905 by militant unionists and their supporters due to anger over the conservatism, philosophy, and craft-based structure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the philosophy and tactics of the IWW were frequently in direct conflict with those of the AFL concerning the best ways to organize workers, and how to best improve the society in which they toiled. The AFL had one guiding principle—"pure and simple trade unionism", often summarized with the slogan "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work." The IWW embraced two guiding principles, fighting like the AFL for better wages, hours, and conditions, but also promoting an eventual, permanent solution to the problems of strikes, injunctions, bull pens, and union scabbing.

Dangerous Hours is a 1919 American silent drama film directed by Fred Niblo. Prints of the film survive in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. It premiered in February 1920.

The Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO), later known as the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union, was an organization of farm workers throughout the United States and Canada formed on April 15, 1915, in Kansas City. It was supported by, and a subsidiary organization of, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Although the IWW had advocated the abolition of the wage system as an ultimate goal since its own formation ten years earlier, the AWO's founding convention sought rather to address immediate needs, and championed a ten-hour work day, premium pay for overtime, a minimum wage, good food and bedding for workers. In 1917 the organization changed names to the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (AWIU) as part of a broader reorganization of IWW industrial unions.

Erwin Bratton "Harry" Ault (1883–1961) was an American socialist and trade union activist. He is best remembered as the editor of the Seattle Union Record, the long-running labor weekly published from 1912 to 1928. After termination of the Union Record, Ault worked as a commercial printer for a number of years, before being appointed a deputy U.S. Marshal for Tacoma, Washington, a position which he retained for 15 years.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905. The IWW experienced a number of divisions and splits during its early history.

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions of political, social, and labour organizations and may also include rallies, marches, boycotts, civil disobedience, non-payment of taxes, and other forms of direct or indirect action. Additionally, general strikes might exclude care workers, such as teachers, doctors, and nurses.

The United States strike wave of 1919 was a succession of extensive labor strikes following World War I that unfolded across various American industries, involving more than four million American workers. This significant post-war labor mobilization marked a critical juncture in the nation's industrial landscape, with widespread strikes reflecting the heightened socioeconomic tensions and the burgeoning demand for improved working conditions and fair labor practices.

The 1916 West Coast waterfront strike was the first coast-wide strike of longshore workers on the Pacific Coast of the United States. The strike was a major defeat for the International Longshoremen's Association, and its membership declined significantly over the next decade. Employers won control over hiring halls and started a campaign to drive out the union's remaining presence.