The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.

In Dubious Battle is a novel by John Steinbeck, written in 1936. The central figure of the story is an activist attempting to organize abused laborers in order to gain fair wages and working conditions.

The Centralia Tragedy, also known as the Centralia Conspiracy and the Armistice Day Riot, was a violent and bloody incident that occurred in Centralia, Washington, on November 11, 1919, during a parade celebrating the first anniversary of Armistice Day. The conflict between the American Legion and Industrial Workers of the World members resulted in six deaths, others being wounded, multiple prison terms, and an ongoing and especially bitter dispute over the motivations and events that precipitated the event. Both Centralia and the neighboring town of Chehalis had a large number of World War I veterans, with robust chapters of the Legion and many IWW members, some of whom were also war veterans.

The Everett massacre, also known as Bloody Sunday, was an armed confrontation between local authorities and members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union, commonly called "Wobblies". It took place in Everett, Washington, on Sunday, November 5, 1916. The event marked a time of rising tensions in Pacific Northwest labor history.

The Wheatland hop riot was a violent confrontation during a strike of agricultural workers demanding decent working conditions at the Durst Ranch in Wheatland, California, on August 3, 1913. The riot, which resulted in four deaths and numerous injuries, was subsequently blamed by local authorities, who were controlled by management, upon the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The Wheatland hop riot was among the first major farm labor confrontations in California and a harbinger of further such battles in the United States throughout the 20th century.

On April 21, 1920, during a miners strike in Butte, Montana's copper mines, company guards fired on striking miners picketing near a mine of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, killing Tom Manning and injuring sixteen others, an event known as the Anaconda Road massacre. His death went unpunished.

The Hardin County onion pickers strike was a strike by agricultural workers in Hardin County, Ohio, in 1934. Led by the Agricultural Workers Union, Local 19724, the strike began on June 20, two days after the trade union formed. After the kidnapping and beating of the union's leader and the intervention of the Ohio National Guard on behalf of the growers, the strike ended in October with a partial victory for the union. Some growers met the union's demand for a 35-cents-an-hour minimum wage, but the majority did not.

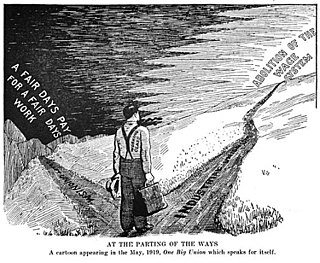

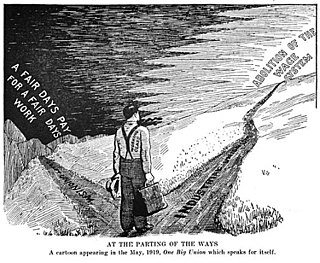

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905 by militant unionists and their supporters due to anger over the conservatism, philosophy, and craft-based structure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the philosophy and tactics of the IWW were frequently in direct conflict with those of the AFL concerning the best ways to organize workers, and how to best improve the society in which they toiled. The AFL had one guiding principle—"pure and simple trade unionism", often summarized with the slogan "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work." The IWW embraced two guiding principles, fighting like the AFL for better wages, hours, and conditions, but also promoting an eventual, permanent solution to the problems of strikes, injunctions, bull pens, and union scabbing.

The Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO), later known as the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union, was an organization of farm workers throughout the United States and Canada formed on April 15, 1915, in Kansas City. It was supported by, and a subsidiary organization of, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Although the IWW had advocated the abolition of the wage system as an ultimate goal since its own formation ten years earlier, the AWO's founding convention sought rather to address immediate needs, and championed a ten-hour work day, premium pay for overtime, a minimum wage, good food and bedding for workers. In 1917 the organization changed names to the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (AWIU) as part of a broader reorganization of IWW industrial unions.

Caroline Decker Gladstein was a labor activist in the 1930s in California. A member of the Communist Party, as many activists were, she was an organizer for the Cannery and Agricultural Workers’ International Union (CAWIU). Decker helped organize the massive California agricultural strikes of 1933 during the Great Depression.

The California agricultural strikes of 1933 were a series of strikes by mostly Mexican and Filipino agricultural workers throughout the San Joaquin Valley. More than 47,500 workers were involved in the wave of approximately 30 strikes from 1931-1941. Twenty-four of the strikes, involving 37,500 union members, were led by the Cannery and Agricultural Workers' Industrial Union (CAWIU). The strikes are grouped together because most of them were organized by the CAWIU. Strike actions began in August among cherry, grape, peach, pear, sugar beet, and tomato workers, and culminated in a number of strikes against cotton growers in the San Joaquin Valley in October. The cotton strikes involved the largest number of workers. Sources vary as to numbers involved in the cotton strikes, with some sources claiming 18,000 workers and others just 12,000 workers, 80% of whom were Mexican.

The Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) was a Communist-aligned union active in California in the early 1930s. Organizers provided support to workers in California's fields and canning industry. The Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) dated back to 1929 with the formation of the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL). With industrialization and the advent of the factories, labor started migrating into the urban space. An influx of immigrant workers contributed to the environment favorable to big business by increasing the supply of unskilled labor lost to the urban factories. The demand for labor spurred the growers to look to seasonal migrant workers as a viable labor source. Corporations began to look at profits and started to marginalize its workers by providing sub-par wages and working conditions to their seasonal workers. The formation of the Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union addressed and represented the civil rights of the migrant workers. Ultimately the CAWIU lost the battle, overwhelmed by the combined alliance of growers and the Mexican and state governments. The eventual abandonment of the Trade Union Unity League led to the dissolution of the CAWIU, which later emerged as the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA).

The Imperial Valley lettuce strike of 1930 was a strike of workers against lettuce growers of California's Imperial Valley

The El Monte berry strike began on June 1, 1933 in El Monte, California. It was part of the largest California agricultural strike of 1933, organized by the Cannery and Agricultural Workers’ International Union (CAWIU). The berry strike affected local Japanese farm owners and growers.

The Salinas California lettuce strike of 1934 ran from August 27 to September 24, 1934, in the Salinas Valley of California. This strike of lettuce cutters and shed workers was begun and largely maintained by the recently formed Filipino Labor Union and came to highlight ethnic discrimination and union repression. Acts of violence from both frustrated workers and vigilante bands threatened the strike's integrity

In 1933 there was a cherry strike in Santa Clara, California. The main overview of the events in Santa Clara was an agricultural strike by cherry pickers against the growers or employers. As the events of the labor strike unfolded, the significance of the strike grew beyond that of the workers themselves into a broader scope within America.

Pat Chambers was an influential labor organizer and Communist Party member in the 1930s in California. He was a key figure in some of the largest California agricultural strikes of 1933. Chambers was the inspiration for the character “Mac” in John Steinbeck's 1936 novel, In Dubious Battle.

The Citrus Strike of 1936 was a strike in southern California among citrus workers for better working conditions that took place in Orange County from June 10 to July 25. The strike was significant for ending the myth of "contented Mexican labor." It was one of the most violently suppressed strikes of the early 20th century in the United States. The sheriff who suppressed the largely Mexican 3,000 citrus pickers was himself a citrus rancher who issued a "shoot to kill" order on the strikers. 400 pickers were arrested in total, while others were ordered to either face jail time or deportation to Mexico. It has also been referred to as the Citrus War and the Citrus Riots.

The 1912–1913 Little Falls textile strike was a labor strike involving workers at two textile mills in Little Falls, New York, United States. The strike began on October 9, 1912, as a spontaneous walkout of primarily immigrant mill workers at the Phoenix Knitting Mill following a reduction in pay, followed the next week by workers at the Gilbert Knitting Mill for the same reason. The strike, which grew to several hundred participants under the leadership of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), lasted until January the following year, when the mills and the strikers came to an agreement that brought the workers back to the mills on January 6.

The 1927–1928 Colorado Coal Strike was a spreading strike, spearheaded by the Industrial Workers of the World. The exact number of workers involved is unclear due to the nature of the strike. However, it shutdown nearly all of Colorado's coal mines.