The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.

William Ernst Trautmann was an American trade unionist who was the founding general-secretary of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and one of six people who initially laid plans for the organization in 1904.

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations.

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of America. During the first two decades of the 20th century, Haywood was involved in several important labor battles, including the Colorado Labor Wars, the Lawrence Textile Strike, and other textile strikes in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

Franklin Henry Little, commonly known as Frank Little, was an American labor leader who was murdered in Butte, Montana. No one was apprehended or prosecuted for Little's murder. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, organizing miners, lumberjacks, and oil field workers. He was a member of the union's Executive Board when he was brutally murdered.

Labor aristocracy or labour aristocracy has at least four meanings: (1) as a term with Marxist theoretical underpinnings; (2) as a specific type of trade unionism; (3) as a shorthand description by revolutionary industrial unions for the bureaucracy of craft-based business unionism; and (4) in the 19th and early 20th centuries was also a phrase used to define better-off members of the working class.

The Industrial Worker, "the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism", is the magazine of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). It is currently released quarterly. The publication is printed and edited by union labor, and is frequently distributed at radical bookstores, demonstrations, strikes and labor rallies. It covers industrial conditions, strikes, workplace organizing experiences, and features on labor history. It used to be released as a newspaper.

The Wheatland hop riot was a violent confrontation during a strike of agricultural workers demanding decent working conditions at the Durst Ranch in Wheatland, California, on August 3, 1913. The riot, which resulted in four deaths and numerous injuries, was subsequently blamed by local authorities, who were controlled by management, upon the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The Wheatland hop riot was among the first major farm labor confrontations in California and a harbinger of further such battles in the United States throughout the 20th century.

Free speech fights are struggles over free speech, and especially those struggles which involved the Industrial Workers of the World and their attempts to gain awareness for labor issues by organizing workers and urging them to use their collective voice. During the World War I period in the United States, the IWW members, engaged in free speech fights over labor issues which were closely connected to the developing industrial world as well as the Socialist Party. The Wobblies, along with other radical groups, were often met with opposition from local governments and especially business leaders, in their free speech fights.

Labor federation competition in the United States is a history of the labor movement, considering U.S. labor organizations and federations that have been regional, national, or international in scope, and that have united organizations of disparate groups of workers. Union philosophy and ideology changed from one period to another, conflicting at times. Government actions have controlled, or legislated against particular industrial actions or labor entities, resulting in the diminishing of one labor federation entity or the advance of another.

Silent agitators are stickers used by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

When Bill Haywood used a board to gavel to order the first convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), he announced, "this is the Continental Congress of the working class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working class..."

Wobbly lingo is a collection of technical language, jargon, and historic slang used by the Industrial Workers of the World, known as the Wobblies, for more than a century. Many Wobbly terms derive from or are coextensive with hobo expressions used through the 1940s.

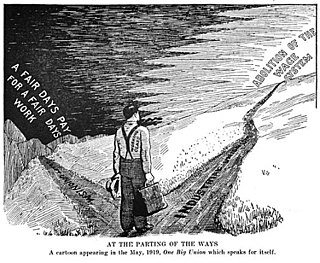

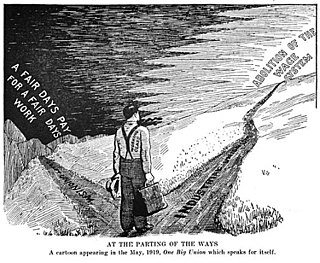

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905 by militant unionists and their supporters due to anger over the conservatism, philosophy, and craft-based structure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the philosophy and tactics of the IWW were frequently in direct conflict with those of the AFL concerning the best ways to organize workers, and how to best improve the society in which they toiled. The AFL had one guiding principle—"pure and simple trade unionism", often summarized with the slogan "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work." The IWW embraced two guiding principles, fighting like the AFL for better wages, hours, and conditions, but also promoting an eventual, permanent solution to the problems of strikes, injunctions, bull pens, and union scabbing.

The Lumber Workers' Industrial Union (LWIU) was a labor union in the United States and Canada which existed between 1917 and 1924. It organised workers in the timber industry and was affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905. The IWW experienced a number of divisions and splits during its early history.

The 1933 Yakima Valley strike took place on 24 August 1933 in the Yakima Valley, Washington, United States. It is notable as the most serious and highly publicized agricultural labor disturbance in Washington history and as a brief revitalization of the Industrial Workers of the World in the region.

The Goldfield, Nevada labor troubles of 1906–1907 were a series of strikes and a lockout which pitted gold miners and other laborers, represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), against mine owners and businessmen.

The 1916–1917 northern Minnesota lumber strike was a labor strike involving several thousand sawmill workers and lumberjacks in the northern part of the U.S. state of Minnesota, primarily along the Mesabi Range. The lumber workers were organized by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and primarily worked for the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company, whose sawmill plant was located in Virginia, Minnesota. Additional lumberjacks and mill workers from the International Lumber Company were also involved. The strike first began with the Virginia and Rainy Lake mill workers on December 28, 1916, and among the lumberjacks on January 1, 1917. The strike lasted for a little over a month before it was officially called off by the union on February 1, 1917. Though the strike faltered by late January and had resulted in many arrests and the suppression of the IWW's local union in the region, the union claimed a partial victory, as the lumber companies instituted some improvements for the lumberjacks' working conditions.