The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ratified on February 3, 1870, as the third and last of the Reconstruction Amendments.

The Twenty-fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution prohibits both Congress and the states from conditioning the right to vote in federal elections on payment of a poll tax or other types of tax. The amendment was proposed by Congress to the states on August 27, 1962, and was ratified by the states on January 23, 1964.

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915), was a United States Supreme Court decision that found certain grandfather clause exemptions to literacy tests for voting rights to be unconstitutional. Though these grandfather clauses were superficially race-neutral, they were designed to protect the voting rights of illiterate white voters while disenfranchising black voters.

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the "one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion of the young and non-citizens. At the same time, some insist that more inclusion is needed before suffrage can be truly universal. Democratic theorists, especially those hoping to achieve more universal suffrage, support presumptive inclusion, where the legal system would protect the voting rights of all subjects unless the government can clearly prove that disenfranchisement is necessary. Universal full suffrage includes both the right to vote, also called active suffrage, and the right to be elected, also called passive suffrage.

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or being grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from the new rule are said to have grandfather rights or acquired rights, or to have been grandfathered in. Frequently, the exemption is limited, as it may extend for a set time, or it may be lost under certain circumstances; for example, a grandfathered power plant might be exempt from new, more restrictive pollution laws, but the exception may be revoked and the new rules would apply if the plant were expanded. Often, such a provision is used as a compromise or out of practicality, to allow new rules to be enacted without upsetting a well-established logistical or political situation. This extends the idea of a rule not being retroactively applied.

From the first United States Congress in 1789 through the 116th Congress in 2020, 162 African Americans served in Congress. Meanwhile, the total number of all individuals who have served in Congress over that period is 12,348. Between 1789 and 2020, 152 have served in the House of Representatives, 9 have served in the Senate, and 1 has served in both chambers. Voting members have totaled 156, with 6 serving as delegates. Party membership has been 131 Democrats and 31 Republicans. While 13 members founded the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971 during the 92nd Congress, in the 116th Congress (2019-2020), 56 served, with 54 Democrats and 2 Republicans.

Voting rights, specifically enfranchisement and disenfranchisement of different groups, has been a moral and political issue throughout United States history.

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized parties to set their internal rules, including the use of white primaries. The court ruled that it was unconstitutional for the state to delegate its authority over elections to parties in order to allow discrimination to be practiced. This ruling affected all other states where the party used the white primary rule.

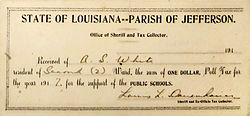

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966), was a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court found that Virginia's poll tax was unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, eleven southern states established poll taxes as part of their disenfranchisement of most blacks and many poor whites. The Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1964) prohibited poll taxes in federal elections; five states continued to require poll taxes for voters in state elections. By this ruling, the Supreme Court banned the use of poll taxes in state elections.

The Reconstruction Amendments, or the Civil War Amendments, are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870. The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which occurred after the Civil War.

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Carolina (1896), Florida (1902), Mississippi and Alabama, Texas (1905), Louisiana and Arkansas (1906), and Georgia (1900). Since winning the Democratic primary in the South almost always meant winning the general election, barring black and other minority voters meant they were in essence disenfranchised. Southern states also passed laws and constitutions with provisions to raise barriers to voter registration, completing disenfranchisement from 1890 to 1908 in all states of the former Confederacy.

Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era in the United States, especially in the Southern United States, was based on a series of laws, new constitutions, and practices in the South that were deliberately used to prevent black citizens from registering to vote and voting. These measures were enacted by the former Confederate states at the turn of the 20th century. Efforts were also made in Maryland, Kentucky, and Oklahoma. Their actions were designed to thwart the objective of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1870, which prohibited states from depriving voters of their voting rights based on race. The laws were frequently written in ways to be ostensibly non-racial on paper, but were implemented in ways that selectively suppressed black voters apart from other voters.

Voter suppression in the United States consists of various legal and illegal efforts to prevent eligible citizens from exercising their right to vote. Such voter suppression efforts vary by state, local government, precinct, and election. Voter suppression has historically been used for racial, economic, gender, age and disability discrimination. After the American Civil War, all African-American men were granted voting rights, but poll taxes or language tests were used to limit and suppress the ability to register or cast a ballot. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 improved voting access significantly. Since the beginning of voter suppression efforts, proponents of these laws have cited concerns over electoral integrity as a justification for various restrictions and requirements, while opponents argue that these constitute bad faith given the lack of voter fraud evidence in the United States.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

This is a timeline of voting rights in the United States, documenting when various groups in the country gained the right to vote or were disenfranchised.

African Americans were fully enfranchised in practice throughout the United States by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Prior to the Civil War and the Reconstruction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, some Black people in the United States had the right to vote, but this right was often abridged or taken away. After 1870, Black people were theoretically equal before the law, but in the period between the end of Reconstruction era and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 this was frequently infringed in practice.

The women's poll tax repeal movement was a movement in the United States, predominantly led by women, that attempted to secure the abolition of poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting in the Southern states. The movement began shortly after the ratification in 1920 of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which granted suffrage to women. Before obtaining the right to vote, women were not obliged to pay the tax, but shortly after the Nineteenth Amendment became law, Southern states began examining how poll tax statutes could be applied to women. For example, North and South Carolina exempted women from payment of the tax, while Georgia did not require women to pay it unless they registered to vote. In other Southern states, the tax was due cumulatively for each year someone had been eligible to vote.

Early women's suffrage work in Alabama started in the 1860s. Priscilla Holmes Drake was the driving force behind suffrage work until the 1890s. Several suffrage groups were formed, including a state suffrage group, the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO). The Alabama Constitution had a convention in 1901 and suffragists spoke and lobbied for women's rights provisions. However, the final constitution continued to exclude women. Women's suffrage efforts were mainly dormant until the 1910s when new suffrage groups were formed. Suffragists in Alabama worked to get a state amendment ratified and when this failed, got behind the push for a federal amendment. Alabama did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1953. For many years, both white women and African American women were disenfranchised by poll taxes. Black women had other barriers to voting including literacy tests and intimidation. Black women would not be able to fully access their right to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

National Committee to Abolish the Poll Tax was an organization founded in 1941 by civil rights activists Joseph Gelders and Virginia Durr to obtain federal action to override poll tax legislation in the Southern United States, which was used to restrict voter rights.