Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebrates; many species live in shallow and tidal waters. Some 2,100 species have been described.

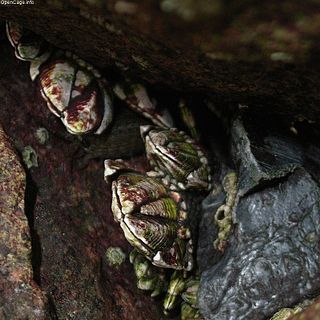

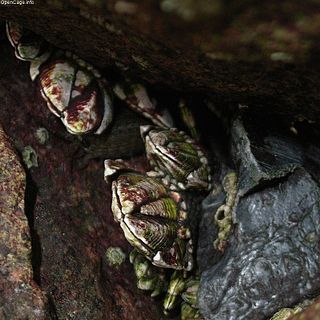

Goose barnacles, also called percebes or turtle-claw barnacles or stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerly made up the taxonomic order Pedunculata, but the group has been found to be polyphyletic, with its members scattered across multiple orders of the infraclass Thoracica.

Thecostraca is a class of marine invertebrates containing over 2,200 described species. Many species have planktonic larvae which become sessile or parasitic as adults.

Acorn barnacle and acorn shell are vernacular names for certain types of stalkless barnacles, generally excluding stalked or gooseneck barnacles. As adults they are typically cone-shaped, symmetrical, and attached to rocks or other fixed objects in the ocean. Members of the barnacle order Balanomorpha are often called acorn barnacles.

Semibalanus balanoides is a common and widespread boreo-arctic species of acorn barnacle. It is common on rocks and other substrates in the intertidal zone of north-western Europe and both coasts of North America.

Whale barnacles are species of acorn barnacle that belong to the family Coronulidae. They typically attach to baleen whales, and sometimes settle on toothed whales. The whale barnacles diverged from the turtle barnacles about three million years ago.

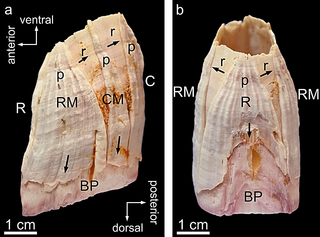

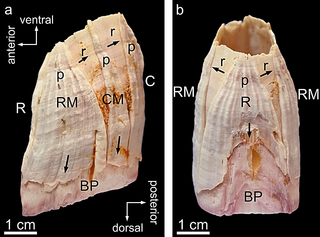

Austromegabalanus psittacus, the giant barnacle or picoroco as it is known in Spanish, is a species of large barnacle native to the coasts of southern Peru, all of Chile and southern Argentina. It inhabits the littoral and intertidal zones of rocky shores and normally grows up to 30 centimetres (12 in) tall with a mineralized shell composed of calcite. The picoroco barnacle is used in Chilean cuisine and is one of the ingredients in curanto.

Chthamalus stellatus, common name Poli's stellate barnacle, is a species of acorn barnacle common on rocky shores in South West England, Ireland, and Southern Europe. It is named after Giuseppe Saverio Poli.

Pollicipes pollicipes, known as the goose neck barnacle, goose barnacle or leaf barnacle is a species of goose barnacle, also well known under the taxonomic synonym Pollicipes cornucopia. It is closely related to Pollicipes polymerus, a species with the same common names, but found on the Pacific coast of North America, and to Pollicipes elegans a species from the coast of Chile. It is found on rocky shores in the north-east Atlantic Ocean and is prized as a delicacy, especially in the Iberian Peninsula.

The Acrothoracica are an infraclass of barnacles.

Amphibalanus improvisus, the bay barnacle, European acorn barnacle, is a species of acorn barnacle in the family Balanidae.

Lepas anserifera is a species of goose barnacle or stalked barnacle in the family Lepadidae. It lives attached to floating timber, ships' hulls and various sorts of flotsam.

Lepas anatifera, commonly known as the pelagic gooseneck barnacle or smooth gooseneck barnacle, is a species of barnacle in the family Lepadidae. These barnacles are found, often in large numbers, attached by their flexible stalks to floating timber, the hulls of ships, piers, pilings, seaweed, and various sorts of flotsam.

Capitulum is a monotypic genus of sessile marine stalked barnacles. Capitulum mitella is the only species in the genus. It is commonly known as the Japanese goose barnacle or kamenote and is found on rocky shores in the Indo-Pacific region.

Catomerus is a monotypic genus of intertidal/shallow water acorn barnacle that is found in warm temperate waters of Australia. The genus and species is very easily identified by whorls of small plates surrounding the base of the primary shell wall; no other shoreline barnacle species in the Southern Hemisphere has that feature. This species is considered to be a relic, as these plates are found only in primitive living lineages of acorn barnacles or in older fossil species. The fact that this is an intertidal species is unusual, because living primitive relic species are often found in more isolated habitats such as deep ocean basins and abyssal hydrothermal vents.

Vulcanolepas osheai, commonly referred to as O'Shea's vent barnacle, is a stalked barnacle of the family Neolepadidae. This species is endemic to New Zealand.

Conchoderma virgatum is a species of goose barnacle in the family Lepadidae. It is a pelagic species found in open water in most of the world's oceans attached to drifting objects or marine organisms.

Clistosaccus is a genus of barnacles which are parasitic on hermit crabs. It is a monotypic genus, and the single species is Clistosaccus paguri, which is found in the northern Atlantic Ocean and the northern Pacific Ocean.

Tetraclita rubescens, commonly known as the pink volcano barnacle, is a species of sessile barnacle in the family Tetraclitidae.

Pollicipes elegans, the Pacific goose barnacle, is a species of gooseneck barnacle inhabiting the tropical coastline of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Its habitat borders a close relative, Pollicipes polymerus, a gooseneck barnacle covering the coastline of the Pacific Northwest. Other species belonging to the genus Pollicipes are found along the eastern coastlines of the Atlantic Ocean.