Related Research Articles

Language acquisition is the process by which humans acquire the capacity to perceive and comprehend language, as well as to produce and use words and sentences to communicate.

Hearing loss is a partial or total inability to hear. Hearing loss may be present at birth or acquired at any time afterwards. Hearing loss may occur in one or both ears. In children, hearing problems can affect the ability to acquire spoken language, and in adults it can create difficulties with social interaction and at work. Hearing loss can be temporary or permanent. Hearing loss related to age usually affects both ears and is due to cochlear hair cell loss. In some people, particularly older people, hearing loss can result in loneliness.

The three models of deafness are rooted in either social or biological sciences. These are the cultural model, the social model, and themedicalmodel. The model through which the deaf person is viewed can impact how they are treated as well as their own self perception. In the cultural model, the Deaf belong to a culture in which they are neither infirm nor disabled, but rather have their own fully grammatical and natural language. In the medical model, deafness is viewed undesirable, and it is to the advantage of the individual as well as society as a whole to "cure" this condition. The social model seeks to explain difficulties experienced by deaf individuals that are due to their environment.

A cochlear implant (CI) is a surgically implanted neuroprosthesis that provides a person who has moderate-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss with sound perception. With the help of therapy, cochlear implants may allow for improved speech understanding in both quiet and noisy environments. A CI bypasses acoustic hearing by direct electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve. Through everyday listening and auditory training, cochlear implants allow both children and adults to learn to interpret those signals as speech and sound.

Lip reading, also known as speechreading, is a technique of understanding a limited range of speech by visually interpreting the movements of the lips, face and tongue without sound. Estimates of the range of lip reading vary, with some figures as low as 30% because lip reading relies on context, language knowledge, and any residual hearing. Although lip reading is used most extensively by deaf and hard-of-hearing people, most people with normal hearing process some speech information from sight of the moving mouth.

Cued speech is a visual system of communication used with and among deaf or hard-of-hearing people. It is a phonemic-based system which makes traditionally spoken languages accessible by using a small number of handshapes, known as cues, in different locations near the mouth to convey spoken language in a visual format. The National Cued Speech Association defines cued speech as "a visual mode of communication that uses hand shapes and placements in combination with the mouth movements and speech to make the phonemes of spoken language look different from each other." It adds information about the phonology of the word that is not visible on the lips. This allows people with hearing or language difficulties to visually access the fundamental properties of language. It is now used with people with a variety of language, speech, communication, and learning needs. It is not a sign language such as American Sign Language (ASL), which is a separate language from English. Cued speech is considered a communication modality but can be used as a strategy to support auditory rehabilitation, speech articulation, and literacy development.

Oralism is the education of deaf students through oral language by using lip reading, speech, and mimicking the mouth shapes and breathing patterns of speech. Oralism came into popular use in the United States around the late 1860s. In 1867, the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts, was the first school to start teaching in this manner. Oralism and its contrast, manualism, manifest differently in deaf education and are a source of controversy for involved communities. Oralism should not be confused with Listening and Spoken Language, a technique for teaching deaf children that emphasizes the child's perception of auditory signals from hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Post-lingual deafness is a deafness which develops after the acquisition of speech and language, usually after the age of six.

The Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, also known as AG Bell, is an organization that aims to promote listening and spoken language among people who are deaf and hard of hearing. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C., with chapters located throughout the United States and a network of international affiliates.

Bimodal bilingualism is an individual or community's bilingual competency in at least one oral language and at least one sign language, which utilize two different modalities. An oral language consists of a vocal-aural modality versus a signed language which consists of a visual-spatial modality. A substantial number of bimodal bilinguals are children of deaf adults (CODA) or other hearing people who learn sign language for various reasons. Deaf people as a group have their own sign language(s) and culture that is referred to as Deaf, but invariably live within a larger hearing culture with its own oral language. Thus, "most deaf people are bilingual to some extent in [an oral] language in some form". In discussions of multilingualism in the United States, bimodal bilingualism and bimodal bilinguals have often not been mentioned or even considered. This is in part because American Sign Language, the predominant sign language used in the U.S., only began to be acknowledged as a natural language in the 1960s. However, bimodal bilinguals share many of the same traits as traditional bilinguals, as well as differing in some interesting ways, due to the unique characteristics of the Deaf community. Bimodal bilinguals also experience similar neurological benefits as do unimodal bilinguals, with significantly increased grey matter in various brain areas and evidence of increased plasticity as well as neuroprotective advantages that can help slow or even prevent the onset of age-related cognitive diseases, such as Alzheimer's and dementia.

The Atlanta Speech School is a language and literacy school located in Atlanta, Georgia, established in 1938. The school provides educational and clinical programs. The Atlanta Speech School's Rollins Center provides professional development for teachers and educators in partner schools and preschools. The Rollins Center focuses on the eradication of illiteracy. The Rollins Center has an online presence called Cox Campus, which is an online learning environment with coursework targeted for the education of children age 0–8.

Congenital hearing loss is a hearing loss present at birth. It can include hereditary hearing loss or hearing loss due to other factors present either in-utero (prenatal) or at the time of birth.

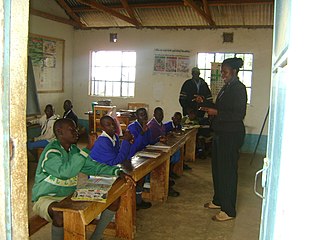

Deaf education is the education of students with any degree of hearing loss or deafness. This may involve, but does not always, individually-planned, systematically-monitored teaching methods, adaptive materials, accessible settings, and other interventions designed to help students achieve a higher level of self-sufficiency and success in the school and community than they would achieve with a typical classroom education. There are different language modalities used in educational setting where students get varied communication methods. A number of countries focus on training teachers to teach deaf students with a variety of approaches and have organizations to aid deaf students.

Auditory-verbal therapy is a method for teaching deaf children to listen and speak using their hearing technology. Auditory-verbal therapy emphasizes listening and seeks to promote the development of the auditory brain to facilitate learning to communicate through talking. It is based on the child's use of optimally fitted hearing technology.

Language deprivation is associated with the lack of linguistic stimuli that are necessary for the language acquisition processes in an individual. Research has shown that early exposure to a first language will predict future language outcomes. Experiments involving language deprivation are very scarce due to the ethical controversy associated with it. Roger Shattuck, an American writer, called language deprivation research "The Forbidden Experiment" because it required the deprivation of a normal human. Similarly, experiments were performed by depriving animals of social stimuli to examine psychosis. Although there has been no formal experimentation on this topic, there are several cases of language deprivation. The combined research on these cases has furthered the research in the critical period hypothesis and sensitive period in language acquisition.

Language acquisition is a natural process in which infants and children develop proficiency in the first language or languages that they are exposed to. The process of language acquisition is varied among deaf children. Deaf children born to deaf parents are typically exposed to a sign language at birth and their language acquisition follows a typical developmental timeline. However, at least 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents who use a spoken language at home. Hearing loss prevents many deaf children from hearing spoken language to the degree necessary for language acquisition. For many deaf children, language acquisition is delayed until the time that they are exposed to a sign language or until they begin using amplification devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. Deaf children who experience delayed language acquisition, sometimes called language deprivation, are at risk for lower language and cognitive outcomes. However, profoundly deaf children who receive cochlear implants and auditory habilitation early in life often achieve expressive and receptive language skills within the norms of their hearing peers; age at implantation is strongly and positively correlated with speech recognition ability. Early access to language through signed language or technology have both been shown to prepare children who are deaf to achieve fluency in literacy skills.

Language deprivation in deaf and hard-of-hearing children is a delay in language development that occurs when sufficient exposure to language, spoken or signed, is not provided in the first few years of a deaf or hard of hearing child's life, often called the critical or sensitive period. Early intervention, parental involvement, and other resources all work to prevent language deprivation. Children who experience limited access to language—spoken or signed—may not develop the necessary skills to successfully assimilate into the academic learning environment. There are various educational approaches for teaching deaf and hard of hearing individuals. Decisions about language instruction is dependent upon a number of factors including extent of hearing loss, availability of programs, and family dynamics.

Language exposure for children is the act of making language readily available and accessible during the critical period for language acquisition. Deaf and hard of hearing children, when compared to their hearing peers, tend to face more hardships when it comes to ensuring that they will receive accessible language during their formative years. Therefore, deaf and hard of hearing children are more likely to have language deprivation which causes cognitive delays. Early exposure to language enables the brain to fully develop cognitive and linguistic skills as well as language fluency and comprehension later in life. Hearing parents of deaf and hard of hearing children face unique barriers when it comes to providing language exposure for their children. Yet, there is a lot of research, advice, and services available to those parents of deaf and hard of hearing children who may not know how to start in providing language.

The Language Equality and Acquisition for Deaf Kids (LEAD-K) campaign is a grassroots organization. Its mission is to work towards kindergarten readiness for deaf and hard-of-hearing children by promoting access to both American Sign Language (ASL) and English. LEAD-K defines kindergarten readiness as perceptive and expressive proficiency in language by the age of five. Deaf and hard-of-hearing children are at high risk of being cut off from language, language deprivation, which can have far-reaching consequences in many areas of development. There are a variety of methods to expose Deaf and hard-of-hearing children to language, including hearing aids, cochlear implants, sign language, and speech and language interventions such as auditory/verbal therapy and Listening and Spoken Language therapy. The LEAD-K initiative was established in response to perceived high rates of delayed language acquisition or language deprivation displayed among that demographic, leading to low proficiency in English skills later in life.

Deaf and hard of hearing individuals with additional disabilities are referred to as "Deaf Plus" or "Deaf+". Deaf children with one or more co-occurring disabilities could also be referred to as hearing loss plus additional disabilities or Deafness and Diversity (D.A.D.). About 40–50% of deaf children experience one or more additional disabilities, with learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and visual impairments being the four most concomitant disabilities. Approximately 7–8% of deaf children have a learning disability. Deaf plus individuals utilize various language modalities to best fit their communication needs.

References

- ↑ CDC (2019-03-21). "Types of Hearing Loss | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ↑ "Speech and Language Developmental Milestones". NIDCD. 2015-08-18. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ↑ CDC (2017-10-23). "Research and Tracking of Hearing Loss in Children | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ↑ "Deafness and HearingLoss" . Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ↑ CDC (2019-12-04). "Summary of Infants Not Passing Hearing Screening Diagnosed by 3 Months". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- 1 2 "Deafness and hearing loss". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ↑ "Audiology Information Series: Childhood Hearing Loss" (PDF). ASHA. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ Duman, Duygu; Tekin, Mustafa (2012-06-01). "Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness genes: a review". Frontiers in Bioscience: A Journal and Virtual Library. 17 (7): 2213–2236. doi:10.2741/4046. ISSN 1093-9946. PMC 3683827 . PMID 22652773.

- ↑ "Hearing Loss at Birth (Congenital Hearing Loss)" . Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ↑ "Hearing Loss at Birth (Congenital Hearing Loss)". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- 1 2 3 Gleason JB, Ratner NB (2009). The development of language (7th ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-205-59303-3.

- 1 2 "Noise Sources and Their Effects" . Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ↑ Polat F (2003-07-01). "Factors Affecting Psychosocial Adjustment of Deaf Students". Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 8 (3): 325–339. doi: 10.1093/deafed/eng018 . PMID 15448056.

- ↑ "Effects of Hearing Loss on Development". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ↑ Rowe, Bruce M. (2015-07-22). A Concise Introduction to Linguistics. doi:10.4324/9781315664491. ISBN 9781315664491. S2CID 60995200.

- 1 2 Bishop D, Mogford K, eds. (1994). Language development in exceptional circumstances (1st ed.). Hove: Erlbaum. ISBN 0-86377-308-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Mayberry R (2002). "chapter 4". In Segalowitz, Rapin (eds.). Handbook of Neuropsychology (2nd ed.). Elsevier Science. pp. 71–107. ISBN 9780444503602.

- ↑ Margolis AC (July 2001). "Implications of prelingual deafness". Lancet. 358 (9275): 76. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05294-6 . PMID 11458947. S2CID 30550367.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McKinley AM, Warren SF (2000). "The Effectiveness of Cochlear Implants for Children With Prelingual Deafness" (PDF). Journal of Early Intervention. 23 (4): 252–263. doi:10.1177/10538151000230040501. S2CID 59361619.

- ↑ Campbell R, MacSweeney M, Woll B (2014-10-17). "Cochlear implantation (CI) for prelingual deafness: the relevance of studies of brain organization and the role of first language acquisition in considering outcome success". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 834. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00834 . PMC 4201085 . PMID 25368567.

- 1 2 3 Andrews J, Logan R, Phelan J (2008). "Milestones of Language Development". Advance for Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists. 18 (2): 16–20.

- ↑ Angier, Natalie (1991-03-22). "Deaf couples' babies found to babble with hands Study compares practice to learning sounds" . Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ↑ Meier R (1991). "Language Acquisition by Deaf Children". American Scientist. 79 (1): 60–70. Bibcode:1991AmSci..79...60M. JSTOR 29774278.

- 1 2 Neville HJ, Bavelier D, Corina D, Rauschecker J, Karni A, Lalwani A, et al. (February 1998). "Cerebral organization for language in deaf and hearing subjects: biological constraints and effects of experience". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (3): 922–929. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95..922N. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.922 . PMC 33817 . PMID 9448260.

- ↑ Meier, Richard P. (1991). "Language Acquisition by Deaf Children". American Scientist. 79 (1): 60–70. Bibcode:1991AmSci..79...60M. ISSN 0003-0996. JSTOR 29774278.