The Fatimid dynasty was an Arab dynasty that ruled the Fatimid Caliphate, between 909 and 1171 CE. Descended from Fatima and Ali, and adhering to Isma'ili Shi'ism, they held the Isma'ili imamate, and were regarded as the rightful leaders of the Muslim community. The line of Nizari Isma'ili imams, represented today by the Aga Khans, claims descent from a branch of the Fatimids. The Alavi Bohras, predominantly based in Vadodara also claim descent from the Fatimids.

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdī biʾllāh, was the founder of the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate, the only major Shi'a caliphate in Islamic history, and the eleventh Imam of the Isma'ili branch of Shi'ism.

The Qarmatians were a militant Isma'ili Shia movement centred in al-Hasa in Eastern Arabia, where they established a religious—and, as some scholars have claimed, proto-socialist or utopian socialist—state in 899 CE. Its members were part of a movement that adhered to a syncretic branch of Sevener Ismaili Shia Islam, and were ruled by a dynasty founded by Abu Sa'id al-Jannabi, a Persian from Jannaba in coastal Fars. They rejected the claim of Fatimid Caliph Abdallah al-Mahdi Billah to imamate and clung to their belief in the coming of the Mahdi, and they revolted against the Fatimid and Abbasid Caliphates.

Abū'l-Ḥasan Mu'nis al-Qushuri, also commonly known by the surnames al-Muẓaffar and al-Khadim, was the commander-in-chief of the Abbasid army from 908 to his death in 933 CE, and virtual dictator and king-maker of the Caliphate from 928 on.

Abu Tahir Sulayman al-Jannabi was a Persian warlord and the ruler of the Qarmatian state in Bahrayn, who in 930 led the Sack of Mecca.

Abu Sa'id Hasan ibn Bahram al-Jannabi was a Persian and the founder of the Qarmatian state in Bahrayn. By 899, his followers controlled large parts of the region, and in 900, he scored a major victory over an Abbasid army sent to subdue him. He captured the local capital, Hajar, in 903, and extended his rule south and east into Oman. He was assassinated in 913, and succeeded by his eldest son Sa'id.

Husayn ibn Hamdan ibn Hamdun ibn al-Harith al-Taghlibi was an early member of the Hamdanid family, who distinguished himself as a general for the Abbasid Caliphate and played a major role in the Hamdanids' rise to power among the Arab tribes in the Jazira.

The Battle of Hama was fought some 24 km (15 mi) from the city of Hama in Syria on 29 November 903 between the forces of the Abbasid Caliphate and pro-Isma'ili Bedouin. The Abbasids were victorious, resulting in the capture and execution of the Isma'ili leadership. This removed the Isma'ili presence in northern Syria, and was followed by the suppression of another revolt in Iraq in 906. More importantly, it paved the way for the Abbasid attack on the autonomous Tulunid dynasty and the reincorporation of the Tulunid domains in southern Syria and Egypt into the Abbasid Caliphate.

Abu'l-Fadl al-Isfahani, also known as the Isfahani Mahdi, was a young Persian man who in 931 CE was declared to be "God incarnate" by the Qarmatian leader of Bahrayn, Abu Tahir al-Jannabi. This new apocalyptic leader, however, caused great disruption by rejecting traditional aspects of Islam, and promoting ties to Zoroastrianism.

Al-Husayn ibn Zakarawayh, also known under his assumed name Sahib al-Shama, was a Qarmatian leader in the Syrian Desert in the early years of the 10th century.

Yahya ibn Zakarawayh, also known under his assumed name Sahib al-Naqa, was a Qarmatian leader in the Syrian Desert in the early years of the 10th century.

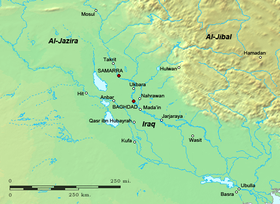

Hamdan Qarmat ibn al-Ash'ath was the eponymous founder of the Qarmatian sect of Isma'ilism. Originally the chief Isma'ili missionary in lower Iraq, in 899 he quarreled with the movement's leadership at Salamiya after it was taken over by Sa'id ibn al-Husayn, and with his followers broke off from them. Hamdan then disappeared, but his followers continued in existence in the Syrian Desert and al-Bahrayn for several decades.

Zakarawayh ibn Mihrawayh, often misspelled as Zikrawayh in modern sources, was an Isma'ili and Qarmatian leader in Iraq who led a series of revolts against the Abbasid Caliphate in the 900s, until his defeat and death in January 907.

The Baqliyya or Būrāniyya were a subgroup of the Qarmatians that was active in southern Iraq in the early 10th century.

The first Fatimid invasion of Egypt occurred in 914–915, soon after the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate in Ifriqiya in 909. The Fatimids launched an expedition east, against the Abbasid Caliphate, under the Berber General Habasa ibn Yusuf. Habasa succeeded in subduing the cities on the Libyan coast between Ifriqiya and Egypt, and captured Alexandria. The Fatimid heir-apparent, al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah, then arrived to take over the campaign. Attempts to conquer the Egyptian capital, Fustat, were beaten back by the Abbasid troops in the province. A risky affair even at the outset, the arrival of Abbasid reinforcements from Syria and Iraq under Mu'nis al-Muzaffar doomed the invasion to failure, and al-Qa'im and the remnants of his army abandoned Alexandria and returned to Ifriqiya in May 915. The failure did not prevent the Fatimids from launching another unsuccessful attempt to capture Egypt four years later. It was not until 969 that the Fatimids conquered Egypt and made it the centre of their empire.

The Sack of Mecca occurred on 11 January 930, when the Qarmatians of Bahrayn sacked the Muslim holy city amidst the rituals of the Hajj pilgrimage.

Abu'l-Qāsim al-Ḥasan ibn Faraj ibn Ḥawshab ibn Zādān al-Najjār al-Kūfī, better known simply as Ibn Ḥawshab, or by his honorific of Manṣūr al-Yaman, was a senior Isma'ili missionary from the environs of Kufa. In cooperation with Ali ibn al-Fadl al-Jayshani, he established the Isma'ili creed in Yemen and conquered much of that country in the 890s and 900s in the name of the Isma'ili imam, Abdallah al-Mahdi, who at the time was still in hiding. After al-Mahdi proclaimed himself publicly in Ifriqiya in 909 and established the Fatimid Caliphate, Ibn al-Fadl turned against him and forced Ibn Hawshab to a subordinate position. Ibn Hawshab's life is known from an autobiography he wrote, while later Isma'ili tradition ascribes two theological treatises to him.

Abu'l-Hayja Abdallah ibn Hamdan was an early member of the Hamdanid dynasty, who served the Abbasid Caliphate as a military commander and governor of Mosul. Esteemed for his qualities, he was involved in the court intrigues at Baghdad, and played a leading role in the brief usurpation of al-Qahir in February 929, during which he was killed. His sons, Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla, went on to found the Hamdanid emirates of Mosul and Aleppo.

The Sack of Basra was the capture and looting of the Abbasid city of Basra by the Qarmatians of Bahrayn, and took place in August 923. It was the first of a series of Qarmatian attacks, that culminated in an invasion of Iraq in 927–928.

In March 924, the Qarmatians of Bahrayn attacked and looted a caravan of Hajj pilgrims making their way back from Mecca to Iraq. The Qarmatians overcame the caravan's armed escort and took many pilgrims prisoner, along with the escort commander, Abu'l-Hayja al-Hamdani, before releasing them for ransom. The raid, along with a failure to prevent a sack of Basra a few months before led to popular unrest in Baghdad, and the deposition and execution of the Abbasid Caliphate's vizier, Ibn al-Furat.