In physics, the fundamental interactions, also known as fundamental forces, are the interactions that do not appear to be reducible to more basic interactions. There are four fundamental interactions known to exist: the gravitational and electromagnetic interactions, which produce significant long-range forces whose effects can be seen directly in everyday life, and the strong and weak interactions, which produce forces at minuscule, subatomic distances and govern nuclear interactions. Some scientists hypothesize that a fifth force might exist, but these hypotheses remain speculative.

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. Particles currently thought to be elementary include the fundamental fermions, which generally are "matter particles" and "antimatter particles", as well as the fundamental bosons, which generally are "force particles" that mediate interactions among fermions. A particle containing two or more elementary particles is a composite particle.

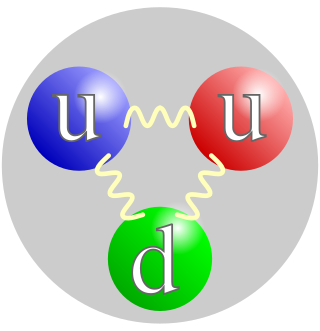

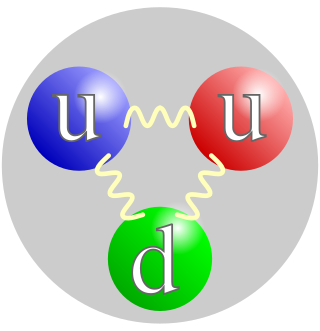

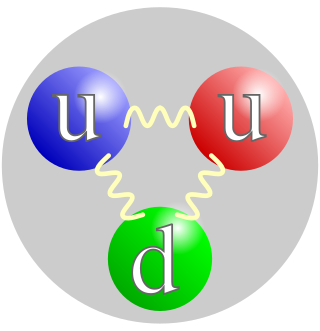

A gluon is an elementary particle that acts as the exchange particle for the strong force between quarks. It is analogous to the exchange of photons in the electromagnetic force between two charged particles. Gluons bind quarks together, forming hadrons such as protons and neutrons.

In particle physics, a hadron is a composite subatomic particle made of two or more quarks held together by the strong interaction. They are analogous to molecules that are held together by the electric force. Most of the mass of ordinary matter comes from two hadrons: the proton and the neutron, while most of the mass of the protons and neutrons is in turn due to the binding energy of their constituent quarks, due to the strong force.

In physics and chemistry, a nucleon is either a proton or a neutron, considered in its role as a component of an atomic nucleus. The number of nucleons in a nucleus defines the atom's mass number.

A quark is a type of elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nuclei. All commonly observable matter is composed of up quarks, down quarks and electrons. Owing to a phenomenon known as color confinement, quarks are never found in isolation; they can be found only within hadrons, which include baryons and mesons, or in quark–gluon plasmas. For this reason, much of what is known about quarks has been drawn from observations of hadrons.

In theoretical physics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the theory of the strong interaction between quarks mediated by gluons. Quarks are fundamental particles that make up composite hadrons such as the proton, neutron and pion. QCD is a type of quantum field theory called a non-abelian gauge theory, with symmetry group SU(3). The QCD analog of electric charge is a property called color. Gluons are the force carriers of the theory, just as photons are for the electromagnetic force in quantum electrodynamics. The theory is an important part of the Standard Model of particle physics. A large body of experimental evidence for QCD has been gathered over the years.

Strong interaction or strong nuclear force is a fundamental interaction that confines quarks into proton, neutron, and other hadron particles. The strong interaction also binds neutrons and protons to create atomic nuclei, where it is called the nuclear force.

The Standard Model of particle physics is the theory describing three of the four known fundamental forces in the universe and classifying all known elementary particles. It was developed in stages throughout the latter half of the 20th century, through the work of many scientists worldwide, with the current formulation being finalized in the mid-1970s upon experimental confirmation of the existence of quarks. Since then, proof of the top quark (1995), the tau neutrino (2000), and the Higgs boson (2012) have added further credence to the Standard Model. In addition, the Standard Model has predicted various properties of weak neutral currents and the W and Z bosons with great accuracy.

An exotic atom is an otherwise normal atom in which one or more sub-atomic particles have been replaced by other particles of the same charge. For example, electrons may be replaced by other negatively charged particles such as muons or pions. Because these substitute particles are usually unstable, exotic atoms typically have very short lifetimes and no exotic atom observed so far can persist under normal conditions.

A timeline of atomic and subatomic physics.

In physical sciences, a subatomic particle is a particle that composes an atom. According to the Standard Model of particle physics, a subatomic particle can be either a composite particle, which is composed of other particles, or an elementary particle, which is not composed of other particles. Particle physics and nuclear physics study these particles and how they interact.

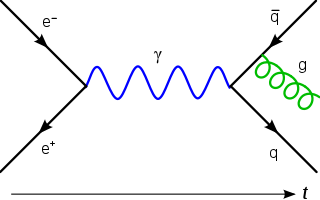

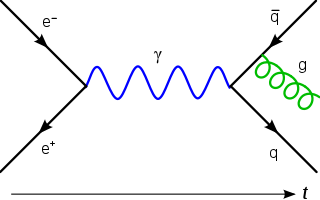

In particle physics, annihilation is the process that occurs when a subatomic particle collides with its respective antiparticle to produce other particles, such as an electron colliding with a positron to produce two photons. The total energy and momentum of the initial pair are conserved in the process and distributed among a set of other particles in the final state. Antiparticles have exactly opposite additive quantum numbers from particles, so the sums of all quantum numbers of such an original pair are zero. Hence, any set of particles may be produced whose total quantum numbers are also zero as long as conservation of energy and conservation of momentum are obeyed.

In particle physics, a gauge boson is a bosonic elementary particle that acts as the force carrier for elementary fermions. Elementary particles, whose interactions are described by a gauge theory, interact with each other by the exchange of gauge bosons, usually as virtual particles.

Exotic hadrons are subatomic particles composed of quarks and gluons, but which — unlike "well-known" hadrons such as protons, neutrons and mesons — consist of more than three valence quarks. By contrast, "ordinary" hadrons contain just two or three quarks. Hadrons with explicit valence gluon content would also be considered exotic. In theory, there is no limit on the number of quarks in a hadron, as long as the hadron's color charge is white, or color-neutral.

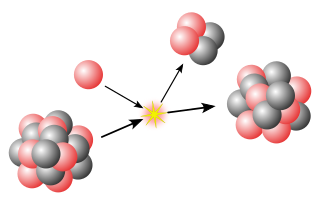

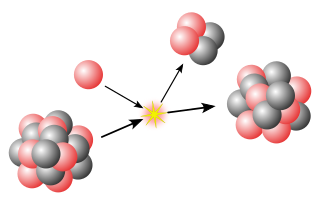

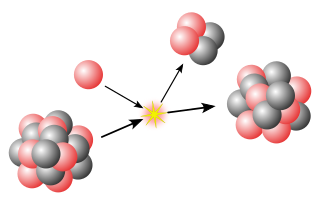

The nuclear force is a force that acts between the protons and neutrons of atoms. Neutrons and protons, both nucleons, are affected by the nuclear force almost identically. Since protons have charge +1 e, they experience an electric force that tends to push them apart, but at short range the attractive nuclear force is strong enough to overcome the electromagnetic force. The nuclear force binds nucleons into atomic nuclei.

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron in 1932, models for a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons were quickly developed by Dmitri Ivanenko and Werner Heisenberg. An atom is composed of a positively charged nucleus, with a cloud of negatively charged electrons surrounding it, bound together by electrostatic force. Almost all of the mass of an atom is located in the nucleus, with a very small contribution from the electron cloud. Protons and neutrons are bound together to form a nucleus by the nuclear force.

In particle physics, a boson ( ) is a subatomic particle whose spin quantum number has an integer value. Bosons form one of the two fundamental classes of subatomic particle, the other being fermions, which have odd half-integer spin. Every observed subatomic particle is either a boson or a fermion.

The idea that matter consists of smaller particles and that there exists a limited number of sorts of primary, smallest particles in nature has existed in natural philosophy at least since the 6th century BC. Such ideas gained physical credibility beginning in the 19th century, but the concept of "elementary particle" underwent some changes in its meaning: notably, modern physics no longer deems elementary particles indestructible. Even elementary particles can decay or collide destructively; they can cease to exist and create (other) particles in result.