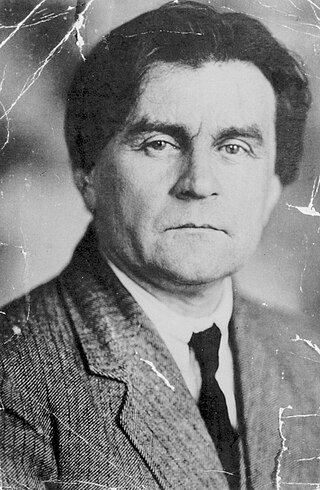

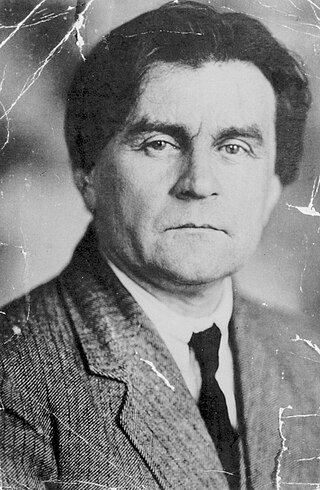

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich was a Russian avant-garde artist and art theorist, whose pioneering work and writing influenced the development of abstract art in the 20th century. He was born in Kiev, modern-day Ukraine, to an ethnic Polish family. His concept of Suprematism sought to develop a form of expression that moved as far as possible from the world of natural forms (objectivity) and subject matter in order to access "the supremacy of pure feeling" and spirituality. Active primarily in Russia, Malevich was a founder of the artists collective UNOVIS and his work has been variously associated with the Russian avant-garde and the Ukrainian avant-garde, and he was a central figure in the history of modern art in Central and Eastern Europe more broadly.

Suprematism is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry, painted in a limited range of colors. The term suprematism refers to an abstract art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.

Lyubov Sergeyevna Popova was a Russian-Soviet avant-garde artist, painter and designer.

UNOVIS was a short-lived but influential group of artists, founded and led by Russian painter Kazimir Malevich at the Vitebsk Art School in 1919.

Cubo-Futurism was an art movement, developed within Russian Futurism, that arose in the early 20th-century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo-Futurism was the main school of painting and sculpture practiced by the Russian Futurists. In 1913, the term "Cubo-Futurism" first came to describe works from members of the poetry group "Hylaeans", as they moved away from poetic Symbolism towards Futurism and zaum, the experimental "visual and sound poetry of Kruchenykh and Khlebninkov". Later in the same year the concept and style of "Cubo-Futurism" became synonymous with the works of artists within Ukrainian and Russian post-revolutionary avant-garde circles as they interrogated non-representational art through the fragmentation and displacement of traditional forms, lines, viewpoints, colours, and textures within their pieces. The impact of Cubo-Futurism was then felt within performance art societies, with Cubo-Futurist painters and poets collaborating on theatre, cinema, and ballet pieces that aimed to break theatre conventions through the use of nonsensical zaum poetry, emphasis on improvisation, and the encouragement of audience participation.

Nina Henrichovna Genke [Hɛŋkə] or Nina Henrichovna Genke-Meller, or Nina Henrichovna Henke-Meller was a Ukrainian-Russian avant-garde artist,, designer, graphic artist and scenographer.

Olga Vladimirovna Rozanova was a Russian avant-garde artist painting in the styles of Suprematism, Neo-Primitivism, and Cubo-Futurism.

Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova was a Russian avant-garde artist, painter and teacher.

Supremus was a group of Russian avant-garde artists led by the "father" of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich. It has been described as the first attempt to found the Russian avant-garde movement as an artistic entity within its own historical development.

Productivism is an early twentieth-century art movement that is characterized by its spare geometry, limited color palette, and Cubist and Futurist influences. Aesthetically, it also looks similar to work by Kazimir Malevich and the Suprematists.

Suprematist Composition (blue rectangle over the red beam) is a 1916 painting by Kazimir Malevich, Russian painter of geometric abstraction.

Ukrainian avant-garde is the avant-garde movement in Ukrainian art from the end of 1890s to the middle of the 1930s along with associated artists in sculpture, painting, literature, cinema, theater, stage design, graphics, music, and architecture. Some well-known Ukrainian avant-garde artists include: Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Archipenko, Vladimir Tatlin, Sonia Delaunay, Vasyl Yermylov, Alexander Bogomazov, Aleksandra Ekster, David Burliuk, Vadym Meller, and Anatol Petrytsky. All were closely connected to the Ukrainian cities of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, and Odesa by either birth, education, language, national traditions or identity. Since it originated when Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire, Ukrainian avant-garde has been commonly lumped by critics into the Russian avant-garde movement.

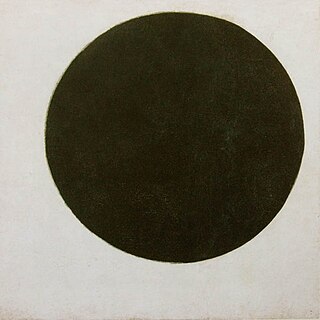

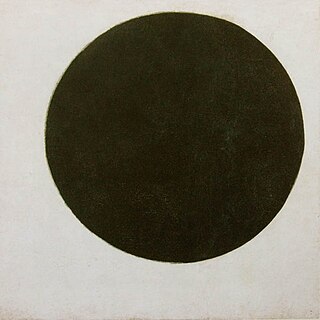

Black Circle is a 1924 oil-on-canvas painting by the Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich, founder of the Suprematism movement. From the mid-1910s, Malevich abandoned any trace of figurature or representation from his paintings in favour of pure abstraction.

Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918) is an abstract oil-on-canvas painting by Kazimir Malevich. It is one of the more well-known examples of the Russian Suprematism movement, painted the year after the October Revolution.

The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 was an exhibition presented by the Dobychina Art Bureau at Marsovo Pole, Petrograd, from 19 December 1915 to 17 January 1916. The exhibition was important in inaugurating a form of non-objective art called Suprematism, introducing a daring visual vernacular composed of geometric forms of varying colour, and in signifying the end of Russia's previous leading art movement, Cubo-Futurism, hence the exhibition's full name. The sort of geometric abstraction relating to Suprematism was distinct in the apparent kinetic motion and angular shapes of its elements.

Matthew Joseph Williams Drutt is an American curator and writer who specializes in modern and contemporary art and design. Based in New York, he has owned and operated his independent consulting practice Drutt Creative Arts Management (DCAM) since 2013. He is currently working with the Lee Ufan Foundation in Arles on an exhibition of non-objective art for Fall 2024. More recently, he worked with the Nationalmuseum Stockholm on an exhibition and publication of modern and contemporary American crafts gifted from artists and collectors in the United States to the museum, originally organized by his mother, Helen Drutt. He has worked more recently with the Eckbo Foundation in Oslo on the first major monograph of Thorwald Hellesen published in English and Norwegian in by Arnoldsche Art Publishers. He is currently also developing several other titles with the publisher. Formerly, he worked with the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland (2013–2016) and the State Hermitage Museum in Russia (2013–2014), consulting on exhibitions, publications, and collections. He continues to serve as an Advisory Curator to the Hermitage Museum Foundation Israel. In 2006, the French Government awarded him the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and in 2003, his exhibition Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism won Best Monographic Exhibition Organized Nationally from the International Association of Art Critics.

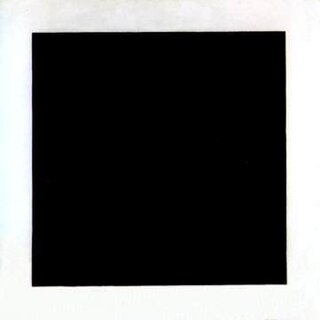

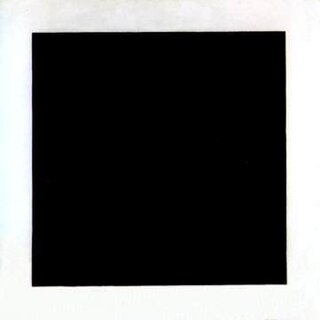

Black Square is a 1915 oil on linen canvas painting by the Russian avant-garde artist and theorist Kazimir Malevich. There are four painted versions, the first of which was completed in 1915 and described by the artist as his breakthrough work and the inception of his Suprematist art movement (1915–1919).

Lazar Markovich Khidekel was an artist, designer, architect and theoretician, who is noted for realizing the abstract, avant-garde Suprematist movement through architecture.

Anna Aleksandrovna Kogan (1902–1974) was a Soviet artist. She was a modernist who worked in several media, including painting, textiles, ceramics, glass and sculpture.

Black Cross is an iconic oil painting by Kazimir Malevich. The first version was done in 1915. From the mid-1910s, Malevich abandoned any trace of figurature or representation from his paintings in favour of pure abstraction.