A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a person who has lost the protection of their country of origin and who cannot or is unwilling to return there due to well-founded fear of persecution. Such a person may be called an asylum seeker until granted refugee status by the contracting state or the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) if they formally make a claim for asylum.

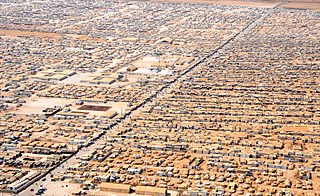

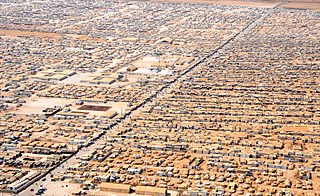

A refugee camp is a temporary settlement built to receive refugees and people in refugee-like situations. Refugee camps usually accommodate displaced people who have fled their home country, but camps are also made for internally displaced people. Usually, refugees seek asylum after they have escaped war in their home countries, but some camps also house environmental and economic migrants. Camps with over a hundred thousand people are common, but as of 2012, the average-sized camp housed around 11,400. They are usually built and run by a government, the United Nations, international organizations, or non-governmental organization. Unofficial refugee camps, such as Idomeni in Greece or the Calais jungle in France, are where refugees are largely left without the support of governments or international organizations.

Immigration to Germany, both in the country's modern borders and the many political entities that preceded it, has occurred throughout the country's history. Today, Germany is one of the most popular destinations for immigrants in the world, with well over 1 million people moving there each year since 2013. As of 2019, around 13.7 million people living in Germany, or about 17% of the population, are first-generation immigrants.

Afghan refugees are citizens of Afghanistan who were forced to flee from their country as a result of wars, persecution, torture or genocide. The 1978 Saur Revolution, followed by the 1979 Soviet invasion, marked the first major wave of internal displacement and international migration to neighboring Iran and Pakistan; smaller numbers also went to India or to countries of the former Soviet Union. Between 1979 and 1992, more than 20% of Afghanistan's population fled the country as refugees. Following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, many returned to Afghanistan, however many Afghans were again forced to flee during the civil war in the 90s. Over 6 million Afghan refugees were residing in Iran and Pakistan by 2000. Most refugees returned to Afghanistan following the 2001 United States invasion and overthrow of the Taliban regime. Between 2002 and 2012, 5.7 million refugees returned to Afghanistan, increasing the country's population by 25%.

Immigration to Turkey is the process by which people migrate to Turkey to reside in the country. Many, but not all, become Turkish citizens. After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and following Turkish War of Independence, an exodus by the large portion of Turkish (Turkic) and Muslim peoples from the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Greece took refuge in present-day Turkey and moulded the country's fundamental features. Trends of immigration towards Turkey continue to this day, although the motives are more varied and are usually in line with the patterns of global immigration movements. Turkey's migrant crisis is a following period since the 2010s, characterized by high numbers of people arriving and settling in Turkey.

Refugees of Iraq are Iraqi nationals who have fled Iraq due to war or persecution. In 1980- 2017, large number of refugees fled Iraq, peaking with the Iraq War and continuing until the end of the War in Iraq (2013–2017). Precipitated by a series of conflicts including the Kurdish rebellions during the Iran–Iraq War, Iraq's Invasion of Kuwait (1990) and the Gulf War (1991), the subsequent sanctions against Iraq (1991–2003), culminating in the Iraq War and the subsequent War in Iraq (2013–2017), millions were forced by insecurity to flee their homes in Iraq. Iraqi refugees established themselves in urban areas in other countries rather than refugee camps.

Palestinians in Iraq are people of Palestinians, most of whom have been residing in Iraq after they were displaced in 1948. Before 2003, there were approximately 34,000 Palestinians thought to be living in Iraq, mainly concentrated in Baghdad. However, since the 2003 Iraq War, the figure lies between 10,000–13,000, although a precise figure has been hard to determine. The situation of Palestinians in Iraq deteriorated after the fall of Saddam Hussein and particularly following the bombing of the Al-Askari Mosque in 2006. Since then, with the rise in insecurity throughout Iraq, they have been the target of expulsion, persecution and violence by Shia militants, and the new Iraqi Government with militant groups targeting them for preferential treatment they received under the Ba'ath Party rule. Currently, several hundred Palestinians from Iraq are living in border camps, after being refused entry to neighbouring Jordan and Syria. Others have been resettled to third countries.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Representation in Cyprus is an office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) opened in August 1974 upon the request of the Government of Cyprus and the Secretary-General of the United Nations. UNHCR Representation in Cyprus was designated as Coordinator of the United Nations Humanitarian Assistance for Cyprus. UNHCR was also responsible upon the request of the Cyprus Government to examine applications for refugee status.

Refugees of the Syrian civil war are citizens and permanent residents of Syria who have fled the country throughout the Syrian civil war. The pre-war population of the Syrian Arab Republic was estimated at 22 million (2017), including permanent residents. Of that number, the United Nations (UN) identified 13.5 million (2016) as displaced persons, requiring humanitarian assistance. Of these, since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011 more than six million (2016) were internally displaced, and around five million (2016) had crossed into other countries, seeking asylum or placed in Syrian refugee camps worldwide. It is often described as one of the largest refugee crises in history.

Qatar Charity is a humanitarian and development non-governmental organization in the Middle East. It was founded in 1992 in response to the thousands of children who were made orphans by the Afghanistan war and while orphans still remain a priority cause in the organization's work with more than 150,000 sponsored orphans, it has now expanded its fields of action to include six humanitarian fields and seven development fields.

Syrian refugee camp and shelters are temporary settlements built to receive internally displaced people and refugees of the Syrian Civil War. Of the estimated 7 million persons displaced within Syria, only a small minority live in camps or collective shelters. Similarly, of the 8 million refugees, only about 10 percent live in refugee camps, with the vast majority living in both urban and rural areas of neighboring countries. Beside Syrians, they include Iraqis, Palestinians, Kurds, Yazidis, individuals from Somalia, and a minority of those who fled the Yemeni and Sudanese civil wars.

Syrians in Lebanon refers to the Syrian migrant workers and, more recently, to the Syrian refugees who fled to Lebanon during the Syrian Civil War. The relationship between Lebanon and Syria includes Maronite-requested aid during Lebanon's Civil War which led to a 29-year occupation of Lebanon by Syria ending in 2005. Following the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War, refugees began entering Lebanon in 2011. Lebanon's response towards the influx of refugees has been criticized as negative, with the Lebanese government leaving them undocumented and limited and attacks on Syrian refugees by Lebanese citizens which go unaddressed by authorities. Despite the strained relationship between the Syrians and Lebanese, taking into consideration only Syrian refugees, Lebanon has the highest number of refugees per capita in the world, with one refugee per four nationals. The power dynamic and position of Syria and Lebanon changed drastically in such a short amount of time, it is inevitable that sentiments and prejudices prevailed despite progressions and changes in circumstance.

During 2015, there was a period of significantly increased movement of refugees and migrants into Europe. 1.3 million people came to the continent to request asylum, the most in a single year since World War II. They were mostly Syrians, but also included significant numbers from Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Iraq, Eritrea, and the Balkans. The increase in asylum seekers has been attributed to factors such as the escalation of various wars in the Middle East and ISIL's territorial and military dominance in the region due to the Arab Winter, as well as Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt ceasing to accept Syrian asylum seekers.

A refugee crisis can refer to difficulties and dangerous situations in the reception of large groups of forcibly displaced persons. These could be either internally displaced, refugees, asylum seekers or any other huge groups of migrants.

This is a timeline of the European migrant crisis of 2015 and 2016.

Syrians in Turkey, includes Turkish citizens of Syrian origin, Syrian refugees, and other Syrian citizens resident in Turkey. As of January 2024, there are approximately 3,200,000 registered refugees of the Syrian Civil War in Turkey, which hosts the biggest refugee population in the whole world. In addition, almost 80,000 Syrian nationals reside in Turkey with a residence permit. Apart from Syrian refugees under temporary protection and Syrian citizens with a residence permit; 238,055 Syrian nationals acquired Turkish citizenship as of December 2023.

Since the onset of the Syrian Civil War in March 2011, over 1.5 million Syrian refugees have fled to Lebanon, and constitute nearly one-fourth of the Lebanese population today. Lebanon currently holds the largest refugee population per capita in the world.

Turkey's migrant crisis, sometimes referred to as Turkey's refugee crisis, was a period during the 2010s characterised by a high number of people migrating to Turkey. Turkey received the highest number of registered refugees of any country or territory each year from 2014 to 2019, and had the world's largest refugee population according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The majority were refugees of the Syrian Civil War, numbering 3.6 million as of June 2020. In 2018, the UNHCR reported that Turkey hosted 63.4% of all "registered Syrian refugees."

The migration and asylum policy of the European Union is within the area of freedom, security and justice, established to develop and harmonise principles and measures used by member countries of the European Union to regulate migration processes and to manage issues concerning asylum and refugee status in the European Union.

The following is a timeline of the Syrian Civil War from September–December 2019. Information about aggregated casualty counts is found at Casualties of the Syrian Civil War.