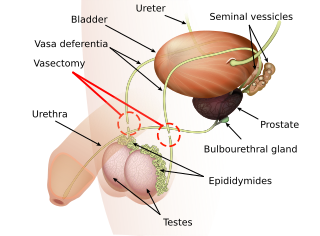

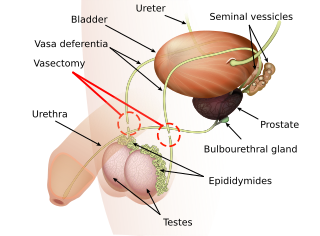

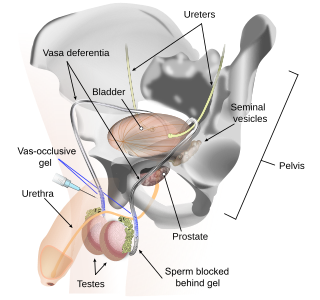

Vasectomy is an elective surgical procedure that results in male sterilization, often as a means of permanent contraception. During the procedure, the male vasa deferentia are cut and tied or sealed so as to prevent sperm from entering into the urethra and thereby prevent fertilization of a female through sexual intercourse. Vasectomies are usually performed in a physician's office, medical clinic, or, when performed on a non-human animal, in a veterinary clinic. Hospitalization is not normally required as the procedure is not complicated, the incisions are small, and the necessary equipment routine.

The vas deferens, with the more modern name ductus deferens, is part of the male reproductive system of many vertebrates. The ducts transport sperm from the epididymides to the ejaculatory ducts in anticipation of ejaculation. The vas deferens is a partially coiled tube which exits the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal.

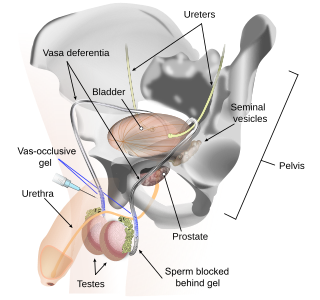

Vas-occlusive contraception is a form of male contraception that blocks sperm transport in the vas deferens, the tubes that carry sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts.

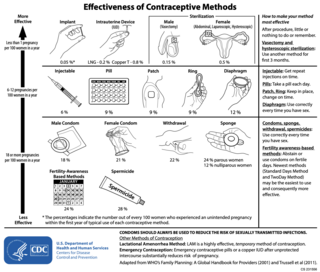

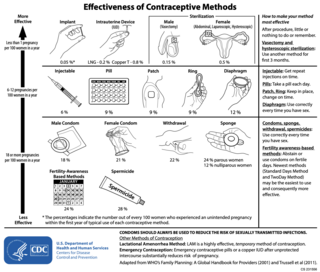

Male contraceptives, also known as male birth control, are methods of preventing pregnancy by interrupting the function of sperm. The main forms of male contraception available today are condoms, vasectomy, and withdrawal, which together represented 20% of global contraceptive use in 2019. New forms of male contraception are in clinical and preclinical stages of research and development, but as of 2024, none have reached regulatory approval for widespread use.

Sujoy Kumar Guha is an Indian biomedical engineer. He was born in Patna, India, 20 June 1940. He did his undergraduate degree (B.Tech.) in electrical engineering from IIT Kharagpur, followed by a master's degree in electrical engineering at IIT, and another master's degree from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Guha later received his Ph.D. in medical physiology from St. Louis University.

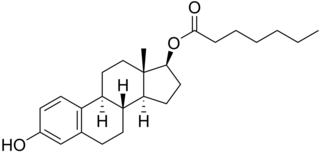

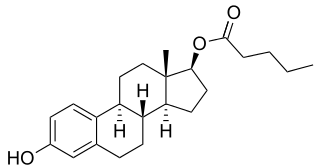

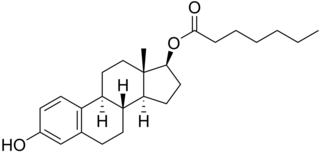

Hormonal contraception refers to birth control methods that act on the endocrine system. Almost all methods are composed of steroid hormones, although in India one selective estrogen receptor modulator is marketed as a contraceptive. The original hormonal method—the combined oral contraceptive pill—was first marketed as a contraceptive in 1960. In the ensuing decades, many other delivery methods have been developed, although the oral and injectable methods are by far the most popular. Hormonal contraception is highly effective: when taken on the prescribed schedule, users of steroid hormone methods experience pregnancy rates of less than 1% per year. Perfect-use pregnancy rates for most hormonal contraceptives are usually around the 0.3% rate or less. Currently available methods can only be used by women; the development of a male hormonal contraceptive is an active research area.

There are many methods of birth control that vary in requirements, side effects, and effectiveness. As the technology, education, and awareness about contraception has evolved, new contraception methods have been theorized and put in application. Although no method of birth control is ideal for every user, some methods remain more effective, affordable or intrusive than others. Outlined here are the different types of barrier methods, hormonal methods, various methods including spermicides, emergency contraceptives, and surgical methods and a comparison between them.

Immunocontraception is the use of an animal's immune system to prevent it from fertilizing offspring. Contraceptives of this type are not currently approved for human use.

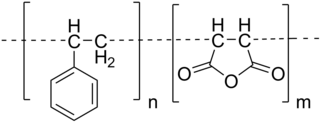

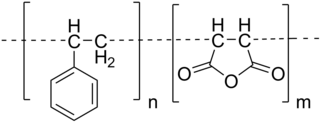

Styrene maleic anhydride is a synthetic polymer that is built-up of styrene and maleic anhydride monomers. The monomers can be almost perfectly alternating, making it an alternating copolymer, but (random) copolymerisation with less than 50% maleic anhydride content is also possible. The polymer is formed by a radical polymerization, using an organic peroxide as the initiator. The main characteristics of SMA copolymer are its transparent appearance, high heat resistance, high dimensional stability, and the specific reactivity of the anhydride groups. The latter feature results in the solubility of SMA in alkaline (water-based) solutions and dispersion.

Combined injectable contraceptives (CICs) are a form of hormonal birth control for women. They consist of monthly injections of combined formulations containing an estrogen and a progestin to prevent pregnancy.

A contraceptive implant is an implantable medical device used for the purpose of birth control. The implant may depend on the timed release of hormones to hinder ovulation or sperm development, the ability of copper to act as a natural spermicide within the uterus, or it may work using a non-hormonal, physical blocking mechanism. As with other contraceptives, a contraceptive implant is designed to prevent pregnancy, but it does not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unintended pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only became available in the 20th century. Planning, making available, and using human birth control is called family planning. Some cultures limit or discourage access to birth control because they consider it to be morally, religiously, or politically undesirable.

Vasectomy reversal is a term used for surgical procedures that reconnect the male reproductive tract after interruption by a vasectomy. Two procedures are possible at the time of vasectomy reversal: vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy. Although vasectomy is considered a permanent form of contraception, advances in microsurgery have improved the success of vasectomy reversal procedures. The procedures remain technically demanding and may not restore the pre-vasectomy condition.

Algestone acetophenide, also known more commonly as dihydroxyprogesterone acetophenide (DHPA) and sold under the brand names Perlutal and Topasel among others, is a progestin medication which is used in combination with an estrogen as a form of long-lasting injectable birth control. It has also been used alone, but is no longer available as a standalone medication. DHPA is not active by mouth and is given once a month by injection into muscle.

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in injectable form and sold under the brand name Depo-Provera among others, is a hormonal medication of the progestin type. It is used as a method of birth control and as a part of menopausal hormone therapy. It is also used to treat endometriosis, abnormal uterine bleeding, paraphilia, and certain types of cancer. The medication is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen. It is taken by mouth, used under the tongue, or by injection into a muscle or fat.

Norethisterone enanthate (NETE), also known as norethindrone enanthate, is a form of hormonal birth control which is used to prevent pregnancy in women. It is used both as a form of progestogen-only injectable birth control and in combined injectable birth control formulations. It may be used following childbirth, miscarriage, or abortion. The failure rate per year in preventing pregnancy for the progestogen-only formulation is 2 per 100 women. Each dose of this form lasts two months with only up to two doses typically recommended.

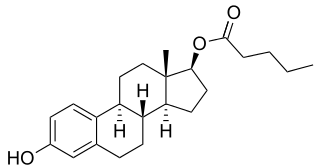

Estradiol enantate, also spelled estradiol enanthate and sold under the brand names Perlutal and Topasel among others, is an estrogen medication which is used in hormonal birth control for women. It is formulated in combination with dihydroxyprogesterone acetophenide, a progestin, and is used specifically as a combined injectable contraceptive. Estradiol enantate is not available for medical use alone. The medication, in combination with DHPA, is given by injection into muscle once a month.

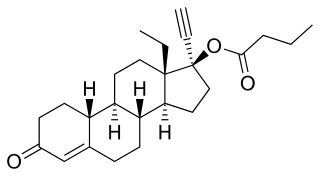

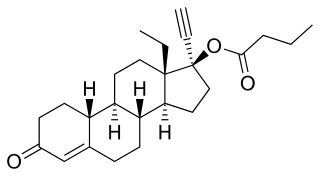

Levonorgestrel butanoate (LNG-B), or levonorgestrel 17β-butanoate, is a steroidal progestin of the 19-nortestosterone group which was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with the Contraceptive Development Branch (CDB) of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as a long-acting injectable contraceptive. It is the C17β butanoate ester of levonorgestrel, and acts as a prodrug of levonorgestrel in the body. The drug is at or beyond the phase III stage of clinical development, but has not been marketed at this time. It was first described in the literature, by the WHO, in 1983, and has been under investigation for potential clinical use since then.

Estradiol enantate/algestone acetophenide, also known as estradiol enantate/dihydroxyprogesterone acetophenide (E2-EN/DHPA) and sold under the brand names Perlutal and Topasel among others, is a form of combined injectable birth control which is used to prevent pregnancy. It contains estradiol enantate (E2-EN), an estrogen, and algestone acetophenide, a progestin. The medication is given once a month by injection into muscle.

Estradiol valerate/megestrol acetate (EV/MGA) is a combined injectable contraceptive which was developed in China in the 1980s but was never marketed. It is an aqueous suspension of microcapsules containing 5 mg estradiol valerate (EV) and 15 mg megestrol acetate (MGA). It was also studied at doses of EV ranging from 0.5 to 5 mg and at doses of MGA ranging from 15 to 25 mg.