Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death. These changes include blebbing, cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and mRNA decay. The average adult human loses between 50 and 70 billion cells each day due to apoptosis. For an average human child between eight and fourteen years old, each day the approximate lost is 20 to 30 billion cells.

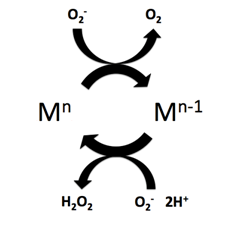

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1) is an enzyme that alternately catalyzes the dismutation (or partitioning) of the superoxide (O−

2) radical into ordinary molecular oxygen (O2) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). Superoxide is produced as a by-product of oxygen metabolism and, if not regulated, causes many types of cell damage. Hydrogen peroxide is also damaging and is degraded by other enzymes such as catalase. Thus, SOD is an important antioxidant defense in nearly all living cells exposed to oxygen. One exception is Lactobacillus plantarum and related lactobacilli, which use a different mechanism to prevent damage from reactive O−

2.

The free radical theory of aging states that organisms age because cells accumulate free radical damage over time. A free radical is any atom or molecule that has a single unpaired electron in an outer shell. While a few free radicals such as melanin are not chemically reactive, most biologically relevant free radicals are highly reactive. For most biological structures, free radical damage is closely associated with oxidative damage. Antioxidants are reducing agents, and limit oxidative damage to biological structures by passivating them from free radicals.

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (O2), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (O2H), superoxide (O2-), hydroxyl radical (OH.), and singlet oxygen. ROS are pervasive because they are readily produced from O2, which is abundant. ROS are important in many ways, both beneficial and otherwise. ROS function as signals, that turn on and off biological functions. They are intermediates in the redox behavior of O2, which is central to fuel cells. ROS are central to the photodegradation of organic pollutants in the atmosphere. Most often however, ROS are discussed in a biological context, ranging from their effects on aging and their role in causing dangerous genetic mutations.

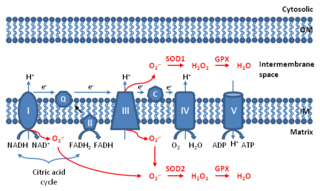

Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] also known as superoxide dismutase 1 or hSod1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the SOD1 gene, located on chromosome 21. SOD1 is one of three human superoxide dismutases. It is implicated in apoptosis, familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Parkinson's disease.

Glutathione peroxidase 1, also known as GPx1, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the GPX1 gene on chromosome 3. This gene encodes a member of the glutathione peroxidase family. Glutathione peroxidase functions in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide, and is one of the most important antioxidant enzymes in humans.

Glisodin is the registered trademark of a nutritional supplement based on two constituents:

Brain mitochondrial carrier protein 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SLC25A14 gene.

Endonuclease G, mitochondrial is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ENDOG gene. This protein primarily participates in caspase-independent apoptosis via DNA degradation when translocating from the mitochondrion to nucleus under oxidative stress. As a result, EndoG has been implicated in cancer, aging, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD). Regulation of its expression levels thus holds potential to treat or ameliorate those conditions.

Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the VDAC2 gene on chromosome 10. This protein is a voltage-dependent anion channel and shares high structural homology with the other VDAC isoforms. VDACs are generally involved in the regulation of cell metabolism, mitochondrial apoptosis, and spermatogenesis. Additionally, VDAC2 participates in cardiac contractions and pulmonary circulation, which implicate it in cardiopulmonary diseases. VDAC2 also mediates immune response to infectious bursal disease (IBD).

Rottlerin (mallotoxin) is a polyphenol natural product isolated from the Asian tree Mallotus philippensis. Rottlerin displays a complex spectrum of pharmacology.

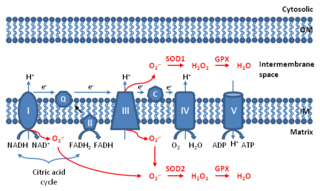

Mitochondrial ROS are reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are produced by mitochondria. Generation of mitochondrial ROS mainly takes place at the electron transport chain located on the inner mitochondrial membrane during the process of oxidative phosphorylation. Leakage of electrons at complex I and complex III from electron transport chains leads to partial reduction of oxygen to form superoxide. Subsequently, superoxide is quickly dismutated to hydrogen peroxide by two dismutases including superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in mitochondrial matrix and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in mitochondrial intermembrane space. Collectively, both superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generated in this process are considered as mitochondrial ROS.

ADP/ATP translocase 2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SLC25A5 gene on the X chromosome.

Oxidation response is stimulated by a disturbance in the balance between the production of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant responses, known as oxidative stress. Active species of oxygen naturally occur in aerobic cells and have both intracellular and extracellular sources. These species, if not controlled, damage all components of the cell, including proteins, lipids and DNA. Hence cells need to maintain a strong defense against the damage. The following table gives an idea of the antioxidant defense system in bacterial system.

Non-Homologous Isofunctional Enzymes (NISE) are two evolutionarily unrelated enzymes that catalyze the same chemical reaction. Enzymes that catalyze the same reaction are sometimes referred to as analogous as opposed to homologous, however it is more appropriate to name them as Non-homologous Isofunctional Enzymes, hence the acronym (NISE). These enzymes all serve the same end function but do so in different organisms without detectable similarity in primary and possibly tertiary structures.

Diallyl trisulfide (DATS), also known as Allitridin, is an organosulfur compound with the formula S(SCH2CH=CH2)2. It is one of several compounds produced by hydrolysis of allicin, including diallyl disulfide and diallyl tetrasulfide; DATS is one of the most potent.

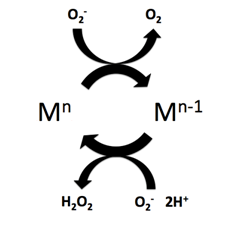

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetics are synthetic compounds that mimic the native superoxide dismutase enzyme. SOD mimetics effectively convert the superoxide anion, a reactive oxygen species, into hydrogen peroxide, which is further converted into water by catalase. Reactive oxygen species are natural byproducts of cellular respiration and cause oxidative stress and cell damage, which has been linked to causing cancers, neurodegeneration, age-related declines in health, and inflammatory diseases. SOD mimetics are a prime interest in therapeutic treatment of oxidative stress because of their smaller size, longer half-life, and similarity in function to the native enzyme.

The mitochondrial theory of ageing has two varieties: free radical and non-free radical. The first is one of the variants of the free radical theory of ageing. It was formulated by J. Miquel and colleagues in 1980 and was developed in the works of Linnane and coworkers (1989). The second was proposed by A. N. Lobachev in 1978.

Kidney ischemia is a disease with a high morbidity and mortality rate. Blood vessels shrink and undergo apoptosis which results in poor blood flow in the kidneys. More complications happen when failure of the kidney functions result in toxicity in various parts of the body which may cause septic shock, hypovolemia, and a need for surgery. What causes kidney ischemia is not entirely known, but several pathophysiology relating to this disease have been elucidated. Possible causes of kidney ischemia include the activation of IL-17C and hypoxia due to surgery or transplant. Several signs and symptoms include injury to the microvascular endothelium, apoptosis of kidney cells due to overstress in the endoplasmic reticulum, dysfunctions of the mitochondria, autophagy, inflammation of the kidneys, and maladaptive repair.

Iron superoxide dismutase (FeSOD) is a metalloenzyme that belongs to the superoxide dismutases family of enzymes. Like other superoxide dismutases, it catalyses the dismutation of superoxides into diatomic oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. Found primarily in prokaryotes such as Escherichia coli and present in all strict anaerobes, examples of FeSOD have also been isolated from eukaryotes, such as Vigna unguiculata.