SS Great Britain is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1853. She was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), for the Great Western Steamship Company's transatlantic service between Bristol and New York City. While other ships had been built of iron or equipped with a screw propeller, Great Britain was the first to combine these features in a large ocean-going ship. She was the first iron steamer to cross the Atlantic Ocean, which she did in 1845, in 14 days.

Cunard Line is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Bermuda.

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships came into practical usage during the early 1800s; however, there were exceptions that came before. Steamships usually use the prefix designations of "PS" for paddle steamer or "SS" for screw steamer. As paddle steamers became less common, "SS" is incorrectly assumed by many to stand for "steamship". Ships powered by internal combustion engines use a prefix such as "MV" for motor vessel, so it is not correct to use "SS" for most modern vessels.

The Blue Riband is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. The record is based on average speed rather than passage time because ships follow different routes. Also, eastbound and westbound speed records are reckoned separately, as the more difficult westbound record voyage, against the Gulf Stream and the prevailing weather systems, typically results in lower average speeds.

SS Savannah was an American hybrid sailing ship/sidewheel steamer built in 1818. She was the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean, transiting mainly under sail power from May to June 1819. In spite of this historic voyage, the great space taken up by her large engine and its fuel at the expense of cargo, and the public's anxiety over embracing her revolutionary steam power, kept Savannah from being a commercial success as a steamship. Originally laid down as a sailing packet, she was, following a severe and unrelated reversal of the financial fortunes of her owners, converted back into a sailing ship shortly after returning from Europe.

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuries after the dwindling of sporadic Viking trade with Markland, a regular and lasting transatlantic trade route was established in 1566 with the Spanish West Indies fleets, following the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

SS Great Eastern was an iron sail-powered, paddle wheel and screw-propelled steamship designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and built by John Scott Russell & Co. at Millwall Iron Works on the River Thames, London, England. She was by far the largest ship ever built at the time of her 1858 launch, and had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refuelling. Her length of 692 feet (211 m) was surpassed only in 1899 by the 705-foot (215 m) 17,274-gross-ton RMS Oceanic, her gross tonnage of 18,915 was only surpassed in 1901 by the 701-foot (214 m) 20,904-gross-ton RMS Celtic and her 4,000-passenger capacity was surpassed in 1913 by the 4,234-passenger SS Imperator. The ship having five funnels was unusual for the time. The vessel also had the largest set of paddle wheels.

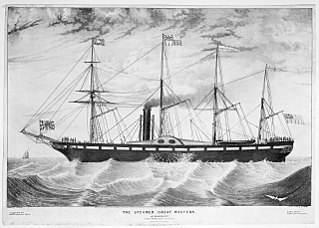

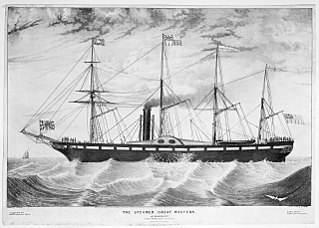

SS Great Western of 1838, was a wooden-hulled paddle-wheel steamship with four masts, the first steamship purpose-built for crossing the Atlantic, and the initial unit of the Great Western Steamship Company. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1837 to 1839, the year the SS British Queen went into service.

SS City of Glasgow of 1850 was a single-screw passenger steamship of the Inman Line, which disappeared en route from Liverpool to Philadelphia in March 1854 with 480 passengers and crew. Based on ideas pioneered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel's SS Great Britain of 1845, City of Glasgow established that Atlantic steamships could be operated profitably without government subsidy. After a refit in 1852, she was also the first Atlantic steamship to carry steerage passengers, representing a significant improvement in the conditions experienced by immigrants. In March 1854 City of Glasgow vanished at sea with no known survivors.

The Collins Line was the common name for the American shipping company started by Israel Collins and then built up by his son Edward Knight Collins, formally called the New York and Liverpool United States Mail Steamship Company. Under Edward Collins' guidance, the company grew to be a serious competitor on the transatlantic routes to the British Cunard shipping company.

SS Pacific was a wooden-hulled, sidewheel steamer built in 1849 for transatlantic service with the American Collins Line. Designed to outclass their chief rivals from the British-owned Cunard Line, Pacific and her three sister ships were the largest, fastest and most well-appointed transatlantic steamers of their day.

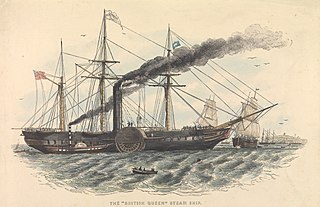

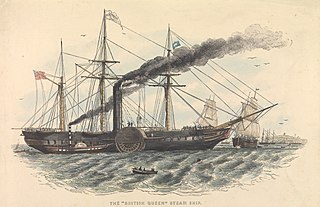

British Queen was a British passenger liner that was the second steamship completed for the transatlantic route when she was commissioned in 1839. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1839 to 1840, then being passed by the SS President. She was named in honor of Queen Victoria and owned by the British and American Steam Navigation Company. British Queen would have been the first transatlantic steamship had she not been delayed by 18 months because of the liquidation of the firm originally contracted to build her engine.

The Great Western Steam Ship Company operated the first regular transatlantic steamer service from 1838 until 1846. Related to the Great Western Railway, it was expected to achieve the position that was ultimately secured by the Cunard Line. The firm's first ship, Great Western was capable of record Blue Riband crossings as late as 1843 and was the model for Cunard's Britannia and her three sisters. The company's second steamer, the Great Britain was an outstanding technical achievement of the age. The company collapsed because it failed to secure a mail contract and Great Britain appeared to be a total loss after running aground. The company might have had a more successful outcome had it built sister ships for Great Western instead of investing in the too advanced Great Britain.

The British and American Steam Navigation Company was a steamship line that operated a regular transatlantic service from 1839 to 1841. Before its first purpose-built Atlantic liner, British Queen was completed, British and American chartered Sirius for two voyages in 1838 to beat the Great Western Steamship Company into service. B & A's regular liners were larger than their rivals, but were underpowered. The company collapsed when its second vessel, President was lost in 1841.

SS Baltic was a wooden-hulled sidewheel steamer built in 1850 for transatlantic service with the American Collins Line. Designed to outclass their chief rivals from the British-owned Cunard Line, Baltic and her three sister ships—Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic—were the largest, fastest and most luxurious transatlantic steamships of their day.

SS Archimedes was a steamship built in Britain in 1839. She was the world's first steamship to be driven successfully by a screw propeller.

Scotia was a British passenger liner operated by the Cunard Line that won the Blue Riband in 1863 for the fastest westbound transatlantic voyage. She was the last oceangoing paddle steamer, and as late as 1874 she made Cunard's second fastest voyage. Laid up in 1876, Scotia was converted to a twin-screw cable layer in 1879. She served in her new role for twenty-five years until she was wrecked off of Guam in March 1904.

The Britannia class was the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddlers that established the first year round scheduled Atlantic steamship service in 1840. By 1845, steamships carried half of the transatlantic saloon passengers and Cunard dominated this trade. While the units of the Britannia class were solid performers, they were not superior to many of the other steamers being placed on the Atlantic at that time. What made the Britannia class successful is that it was the first homogeneous class of transatlantic steamships to provide a frequent and uniform service. Britannia, Acadia and Caledonia entered service in 1840 and Columbia in 1841 enabling Cunard to provide the dependable schedule of sailings required under his mail contracts with the Admiralty. It was these mail contracts that enabled Cunard to survive when all of his early competitors failed.

The America class was the replacement for the Britannia class, the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddle steamers. Entering service starting in 1848, these six vessels permitted Cunard to double its schedule to weekly departures from Liverpool, with alternating sailings to New York. The new ships were also designed to meet new competition from the United States.

SS President was a British passenger liner that was the largest ship in the world when she was commissioned in 1840, and the first steamship to founder on the transatlantic run when she was lost at sea with all 136 onboard in March 1841. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1840 to 1841. The ship's owner, the British and American Steam Navigation Company, collapsed as a result of the disappearance.