Historic uses

From the 1840s to the 1870s, well-to-do merchants and businessmen moved to the College Hill neighborhood of Cincinnati, making it a prestigious rural village characterized by large homes on spacious lots. The presence of two colleges in College Hill attracted abolitionist Presbyterian educators. These educational opportunities attracted Samuel and Sally Wilson, Presbyterians who had been criticized while living in Reading, Ohio, for their abolitionist view. Two of their seven children had previously attended the Cary Academy in College Hill and in 1848 their daughter Mary became a charter faculty member of the Ohio Female College there, which admitted women and employed female faculty.

The Wilsons built their Greek Revival home in College Hill in 1849, after which it became a station on the Underground Railroad until at least 1852. During these years, ten members of the family lived in the house, including four adult children, three grandchildren, and an aunt. In this house the Wilson family made important contributions to the history of the community through their leadership in American educational, religious, political and civic events. The abolitionist efforts of three of the adult children, Mary Jane Wilson Pyle, Harriet Nesmith Wilson, and Joseph Gardner Wilson, are documented in many sources. Mary, widowed in 1848, had been teaching at the College since then, while the youngest daughter Harriet taught in local public schools for 30 years, and lived at the Wilson house from 1849 until her death at age 95 in 1920. The youngest son Joseph was also a local professor, and lived at home until 1852. Joseph collected apparel from the families of this students and cooperated in obtaining disguises for runaways.

While the other four adults who lived in the house are not mentioned by name in existing documentation, they probably assisted fugitive slaves during the years that the house was used as a station. A local publication by the Cincinnati Historic Society states "All the Wilson children were active in the abolitionist movement and aided many Blacks to make their way north by supplying food, clothing, and a hiding place." In the early 20th century several groups of elderly African American men returned to the house and asked to see the cellar where they had once hidden and recognized the Wilsons' former housekeeper, Christine Gramm, still living at the house where she had first been employed in the 1850s. An extensive letter written by Harriet Wilson in 1892 describes her family's efforts helping slaves escape through College Hill. On one occasion when pursuers were headed to College Hill to search for runaway slaves, Harriet state "The women being 'entertained' by our family were terribly frightened declaring 'that they would die rather than be taken and carried back.' Though quite large in size they were ready and willing to crawl through a small aperture into a dark cellar where they would be safe." She states that her sister Mary "was for many years a teacher. . .and were living could give you vivid pictures of the workings of the Underground R.R., for but a few who traveled by it to College Hill, but who were encouraged by her words of cheer and aided by her helping hand." Harriet worked in Cincinnati and returned to College Hill on the weekends. Prior to her trip home on Friday evenings, she was given the number of slaves en route to College Hill so the "stations" were ready for their arrival. She recalls that "frequently, when at home on Saturday and asking for some article of clothing, I would receive the reply, 'Gone to Canada.'"

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Harriet recalled that "the work had become too well known. . . it was deemed wiser to have it carried on by other less exposed routes so in the years immediately preceding the civil war, there were comparatively none coming to the Hill yet those interested in the cause of human rights did their part financially to help in the work. . . ."

The Samuel and Sally Wilson House is located at 1502 Aster Place, in Cincinnati, Ohio. It is a private residence, and is not open to the public.

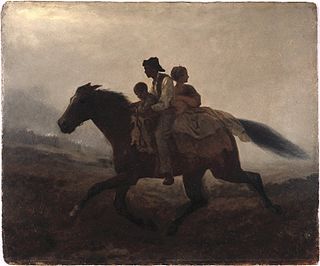

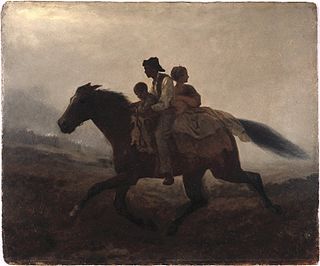

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. The network was assisted by abolitionists and others sympathetic to the cause of the escapees. The enslaved who risked escape and those who aided them are also collectively referred to as the "Underground Railroad". Various other routes led to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished, and to islands in the Caribbean that were not part of the slave trade. An earlier escape route running south toward Florida, then a Spanish possession, existed from the late 17th century until approximately 1790. However, the network now generally known as the Underground Railroad began in the late 18th century. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln. One estimate suggests that by 1850, approximately 100,000 enslaved people had escaped to freedom via the network.

William Still was an African-American abolitionist based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, businessman, writer, historian and civil rights activist. Before the American Civil War, Still was chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. He directly aided fugitive slaves and also kept records of the people served in order to help families reunite.

Levi Coffin was an American Quaker, Republican, abolitionist, farmer, businessman and humanitarian. An active leader of the Underground Railroad in Indiana and Ohio, some unofficially called Coffin the "President of the Underground Railroad," estimating that three thousand fugitive slaves passed through his care. The Coffin home in Fountain City, Wayne County, Indiana, is now a museum, sometimes called the Underground Railroad's "Grand Central Station".

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe enslaved people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the enslaved person had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party.

John P. Parker was an American abolitionist, inventor, iron moulder and industrialist. Parker, who was African American, helped hundreds of slaves to freedom in the Underground Railroad resistance movement based in Ripley, Ohio. He saved and rescued fugitive slaves for nearly fifteen years. He was one of the few black people to patent an invention before 1900. His house in Ripley has been designated a National Historic Landmark and restored.

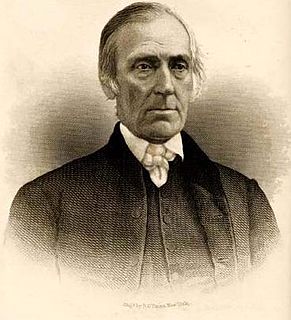

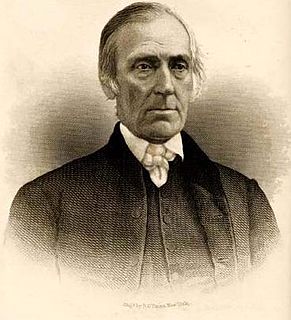

John Rankin was an American Presbyterian minister, educator and abolitionist. Upon moving to Ripley, Ohio, in 1822, he became known as one of Ohio's first and most active "conductors" on the Underground Railroad. Prominent pre-Civil War abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld, Henry Ward Beecher, and Harriet Beecher Stowe were influenced by Rankin's writings and work in the anti-slavery movement.

Margaret Garner, called "Peggy", was an enslaved African-American woman in pre-Civil War America who killed her own daughter rather than allow the child to be returned to slavery. Garner and her family had escaped enslavement in January 1856 by traveling across the frozen Ohio River to Cincinnati, but they were apprehended by U.S. Marshals acting under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Garner's defense attorney, John Jolliffe, moved to have her tried for murder in Ohio, to be able to get a trial in a free state and to challenge the Fugitive Slave Law. Garner's story was the inspiration for the novel Beloved (1987) by Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison and its subsequent adaptation into a film of the same name starring Oprah Winfrey (1998).

Thomas Garrett was an American abolitionist and leader in the Underground Railroad movement before the American Civil War. He helped more than 2,500 African Americans escape slavery.

The Cyrus Gates Farmstead is located in Maine, New York. Cyrus Gates was a cartographer and map maker for New York State, as well as an abolitionist. The great granddaughter of Cyrus-Louise Gates-Gunsalus has stated that from 1848 until the end of slavery in the United States in 1865, the Cyrus Gates Farmstead was a station or stop on the Underground Railroad. Its owners, Cyrus and Arabella Gates, were outspoken abolitionists as well as active and vital members of their community. Historian Shirley L. Woodward states that through those years escaped slaves came through the Gates' station.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is a historic home in Cincinnati, Ohio which was once the residence of influential antislavery author Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Lewis Hayden escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and escaped to Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts to aid in the abolition movement. There he became an abolitionist, lecturer, businessman, and politician. Before the American Civil War, he and his wife Harriet Hayden aided numerous fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, often sheltering them at their house.

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson, "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the 77 slaves who tried to escape from Washington, DC on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

The Coffin House is a National Historic Landmark located in the present-day town of Fountain City in Wayne County, Indiana. The two-story, eight room, brick home was constructed circa 1838–39 in the Federal style. The Coffin home became known as the "Grand Central Station" of the Underground Railroad because of its location where three of the escape routes to the North converged and the number of fleeing slaves who passed through it.

The Underground Railroad in Indiana was part of a larger, unofficial, and loosely-connected network of groups and individuals who aided and facilitated the escape of runaway slaves from the southern United States. The network in Indiana gradually evolved in the 1830s and 1840s, reached its peak during the 1850s, and continued until slavery was abolished throughout the United States at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It is not known how many fugitive slaves escaped through Indiana on their journey to Michigan and Canada. An unknown number of Indiana's abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and people of color, as well as Quakers and other religious groups illegally operated stations along the network. Some of the network's operatives have been identified, including Levi Coffin, the best-known of Indiana's Underground Railroad leaders. In addition to shelter, network agents provided food, guidance, and, in some cases, transportation to aid the runaways.

Lewis and Harriet Hayden House was the home of African-American abolitionists who had escaped from slavery in Kentucky; it is located in Beacon Hill, Boston. They maintained the home as a stop on the Underground Railroad, and the Haydens were visited by Harriet Beecher Stowe as research for her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). Lewis Hayden was an important leader in the African-American community of Boston; in addition, he lectured as an abolitionist and was a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee, which resisted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Raymond S. Lane, Jr. was a sculptor known for creating a series of hand-built clay sculptures about Harriet Tubman. The sculptures were first displayed in 2002 in the Children's Learning Center of the Public Library of Hamilton County’s main building, 800 Vine St., in downtown Cincinnati. The clay works depict scenes in the life of Harriet Tubman as the 19th century Underground Railroad heroine. The exhibit was called “Harriet Tubman's Experience in the Underground Railroad.” The sculptures currently are displayed at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Bartholomew Fussell (1794–1871) was an abolitionist who participated in the Underground Railroad by providing refuge for runaway slaves at his safe house in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania and other locations in Pennsylvania and Ohio. He aided an estimated 2000 slaves in escaping from bondage. He was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Fussell was an advocate for women serving as physicians, and he influenced the founding of the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania. He worked as a practicing physician, including providing medical services for fugitive slaves.

The Dover Eight refers to a group of eight black people who escaped their slaveholders of the Bucktown, Maryland area around March 8, 1857. They were helped along the way by a number of people from the Underground Railroad, except for Thomas Otwell, who turned them in once they had made it north to Dover, Delaware. There, they were lured to the Dover jail with the intention of getting the $3,000 reward for the eight men. The Dover Eight escaped the jail and made it to Canada.

Isaac S. Flint was an Underground Railroad station master, lecturer, farmer, and a teacher. He saved Samuel D. Burris, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, from being sold into slavery after having been caught helping runaway enslaved people.