Related Research Articles

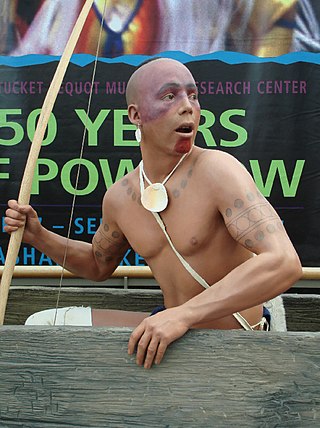

The Pequot are a Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut including the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, or the Brothertown Indians of Wisconsin. They historically spoke Pequot, a dialect of the Mohegan-Pequot language, which became extinct by the early 20th century. Some tribal members are undertaking revival efforts.

Seekonk is a town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States, on the Massachusetts border with Rhode Island. It was incorporated in 1812 from the western half of Rehoboth. The population was 15,531 at the 2020 census. In 1862, under a U.S. Supreme Court decision resolving a longstanding border dispute between Massachusetts and Rhode Island, a portion of Tiverton, Rhode Island was awarded to Massachusetts to become part of Fall River, while two-thirds of Seekonk was awarded to Rhode Island.

King Philip's War was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, the English New England Colonies and their indigenous allies. The war is named for Metacom, the Pokanoket chief and sachem of the Wampanoag who adopted the English name Philip because of the friendly relations between his father Massasoit and the Plymouth Colony. The war continued in the most northern reaches of New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay on April 12, 1678.

The Wampanoag, also rendered Wôpanâak, are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands currently based in southeastern Massachusetts and formerly parts of eastern Rhode Island. Their historical territory includes the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket.

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The Pokanoket was the village governed by Massasoit. The term broadened to refer to all peoples and lands governed by Massasoit and his successors, which were part of the Wampanoag people in what is now Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

State-recognized tribes in the United States are organizations that identify as Native American tribes or heritage groups that do not meet the criteria for federally recognized Indian tribes but have been recognized by a process established under assorted state government laws for varying purposes or by governor's executive orders. State recognition does not dictate whether or not they are recognized as Native American tribes by continually existing tribal nations.

The United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation, also called the Shawnee Nation, United Remnant Band (URB), is an organization that self-identifies as a Native American tribe in Ohio. Its members identify as descendants of Shawnee people. In 2016, the organization incorporated as a church.

Native American tribes in Massachusetts are the Native American tribes and their reservations that existed historically and those that still exist today in what is now the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. A Narragansett term for this region is Ninnimissinuok.

Carcieri v. Salazar, 555 U.S. 379 (2009), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the federal government could not take land into trust that was acquired by the Narragansett Tribe in the late 20th century, as it was not federally recognized until 1983. While well documented in historic records and surviving as a community, the tribe was largely dispossessed of its lands while under guardianship by the state of Rhode Island before suing in the 20th century.

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe is one of two federally recognized tribes of Wampanoag people in Massachusetts. Recognized in 2007, they are headquartered in Mashpee on Cape Cod. The other Wampanoag tribe is the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) on Martha's Vineyard.

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) (Wampanoag: Âhqunah Wôpanâak) is a federally recognized tribe of Wampanoag people based in the town of Aquinnah on the southwest tip of Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts, United States. The tribe hosts an annual Cranberry Day celebration.

The Texas Band of Yaqui Indians is a cultural heritage organization for individuals who identify as descendants of Yaqui people, and are dedicated to cultural and ethnic awareness of the Yaqui. The organization is headquartered in Lubbock, Texas.

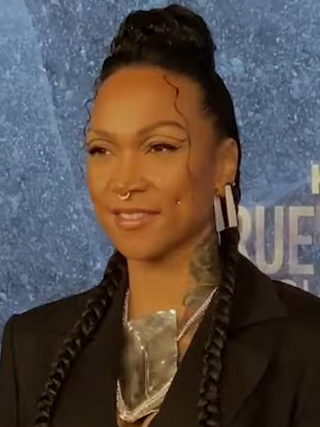

Kali Reis is an American professional boxer and actress. She is a former world champion in two weight classes, having held the WBC female middleweight title in 2016 and the WBA, WBO, and IBO female light welterweight titles between 2020 and 2022. She also challenged Cecilia Brækhus for the undisputed female welterweight title in 2018.

The Massachusett dialects, as well as all the Southern New England Algonquian (SNEA) languages, could be dialects of a common SNEA language just as Danish, Swedish and Norwegian are mutually intelligible languages that essentially exist in a dialect continuum and three national standards. With the exception of Massachusett, which was adopted as the lingua franca of Christian Indian proselytes and survives in hundreds of manuscripts written by native speakers as well as several extensive missionary works and translations, most of the other SNEA languages are only known from fragmentary evidence, such as place names. Quinnipiac (Quiripey) is only attested in a rough translation of the Lord's Prayer and a bilingual catechism by the English missionary Abraham Pierson in 1658. Coweset is only attested in a handful of lexical items that bear clear dialectal variation after thorough linguistic review of Roger Williams' A Key into the Language of America and place names, but most of the languages are only known from local place names and passing mention of the Native peoples in local historical documents.

The Accohannock Indian Tribe, Inc. is a state-recognized tribe in Maryland and a nonprofit organization of individuals who identify as descendants of the Accohannock people.

The Pokanoket Nation, also known as the Pokanoket Tribe, is one of several cultural heritage organizations of individuals who identify as descendants of the Wampanoag people in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. They formed a nonprofit organization called the Council of Seven & Royal House of Pokanoket & Pokanoket Tribe & Wampanoag Corporation in 1994.

The Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe of the Pokanoket Nation is one of several cultural heritage organizations of individuals who identify as descendants of the Wampanoag people in Rhode Island. They formed a nonprofit organization, the Pocasset Pokanoket Land Trust, Inc., in 2017.

The Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe is a cultural heritage group that claims descent from the Wampanoag people based in Plymouth, Massachusetts. They have a nonprofit organization, the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribal Council, Inc.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Seaconke Wampanpoag Tribe–Wampanoag Nation". OpenCorporates. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Seaconke Wampanoag". Cause IQ. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 Douglas-Lithgow, R. A. (2001). Native American Place Names of Rhode Island. Bedford, MA: Applewood Books. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781557095435.

- 1 2 3 4 "Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe-Wompanoag Nation". GuideStar. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Tribal Directory: Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe". National Congress of American Indians. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Indian Affairs Bureau. Federal Register. 23 August 2022. pp. 7554–58. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ↑ "State Recognized Tribes". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ↑ Rehoboth Board of Selectmen (February 1, 1997). "Proclamation" (PDF). State of Rhode Island General Assembly. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ↑ "MA Executive Order 126".

- ↑ "Seaconke Wampanoag Chief, Indian activist and humanitarian dies at 78". Warwick Beacon. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ Waldman, Carl (2014). Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York: Checkmark Books. p. 311. ISBN 9781438110103.

- 1 2 "Seaconke Wampanoag Holds 17th Annual Pow Wow". Reporter Today. 18 September 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ↑ Lawton, Cassie M.; Bial, Raymond (2016). The People and Culture of the Wampanoag. New York: Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 100. ISBN 9781502618993.

- ↑ Tripp, William W. (2 April 2022). "Founding Member of Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe, Lois "Lulu" Chaffee, Dies at 79". GoLocalProv. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ↑ "Greene v. Rhode Island, 289 F. Supp. 2d 5 (D.R.I. 2003)". Justia US Law. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ Doherty, Craig A.; Doherty, Katherine M. (2008). Northeast Indians. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 153. ISBN 9780816059683.

- ↑ Sullivan, Michele M. "Quit Claim Deed of Gift" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ Owens III, James T. (14 April 2008). "Notice of Potential Liability and Request for Information" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ "Peterson/Puritan, Inc., Lincoln/Cumberland, RI". Superfund Site. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ "List of Petitioners By State" (PDF). 12 November 2013. p. 42. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ↑ "Office of Federal Acknowledgment". U.S. Department of Indian Affairs. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ↑ "Indian Affairs". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ "Section 8A: Commission on Indian affairs; membership; functions". The 193rd General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ Burt, Jeffrey (October 10, 1997). "Medicine man John Peters dies at 67". Cape Cod Times. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ "Recognition and Reaffirmation of the Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe" (PDF). State of Rhode Island General Assembly. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ "Rhode Island House Bill 5385". LegiScan. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ "BH 7470". FastDemocracy. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ "Rhode Island Senate Bill 2238". LegiScan. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ↑ "Rhode Island House Bill 7477". LegiScan. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- 1 2 Reardon, Jenny; TallBear, Kim (April 2012). ""Your DNA Is Our History": Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property". Current Anthropology. 53 (S5). doi:10.1086/662629. S2CID 141590148.

- 1 2 Zhadanov, Sergey (August 2010). "Genetic heritage and native identity of the Seaconke Wampanoag tribe of Massachusetts". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (4): 578–89. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21281. PMID 20229500 . Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- 1 2 Sykes, Bryan (2012). DNA USA: A Genetic Portrait of America. New York: Liveright. pp. 280–81. ISBN 9780871404763.

- ↑ "Seakonke Wampanoag Tribe Annual Pow-Wow". Native American Trails Project. University of Massachusetts. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ "Kali Reis". WBAN. Retrieved 17 April 2023.