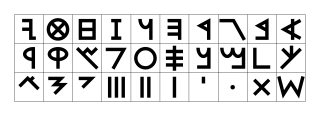

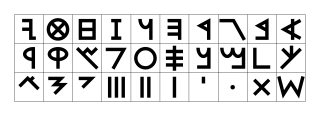

The ancient Aramaic alphabet was used to write the Aramaic languages spoken by ancient Aramean pre-Christian tribes throughout the Fertile Crescent. It was also adopted by other peoples as their own alphabet when empires and their subjects underwent linguistic Aramaization during a language shift for governing purposes — a precursor to Arabization centuries later — including among the Assyrians and Babylonians who permanently replaced their Akkadian language and its cuneiform script with Aramaic and its script, and among Jews, who adopted the Aramaic language as their vernacular and started using the Aramaic alphabet even for writing Hebrew, displacing the former Paleo-Hebrew alphabet.

Manichaeism is a former major world religion, founded in the 3rd century CE by the Parthian prophet Mani, in the Sasanian Empire.

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

Sogdia or Sogdiana was an ancient East Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemenid Empire, and listed on the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great. Sogdiana was first conquered by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, and then was annexed by the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great in 328 BC. It would continue to change hands under the Seleucid Empire, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, the Kushan Empire, the Sasanian Empire, the Hephthalite Empire, the Western Turkic Khaganate and the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.

Turpan is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of 69,759 square kilometres (26,934 sq mi) and a population of 693,988 (2020).

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also known as the Gāndhārī script, was an ancient Indo-Iranian script used by various peoples from the north-western outskirts of the Indian subcontinent to Central Asia via Afghanistan. An abugida, it was introduced at least by the middle of the 3rd century BCE, possibly during the 4th century BCE, and remained in use until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE.

The Sogdian alphabet was originally used for the Sogdian language, a language in the Iranian family used by the people of Sogdia. The alphabet is derived from Syriac, a descendant script of the Aramaic alphabet. The Sogdian alphabet is one of three scripts used to write the Sogdian language, the others being the Manichaean alphabet and the Syriac alphabet. It was used throughout Central Asia, from the edge of Iran in the west, to China in the east, from approximately 100–1200 A.D.

Bactrian is an extinct Eastern Iranian language formerly spoken in the Central Asian region of Bactria and used as the official language of the Kushan and the Hephthalite empires.

In a right-to-left, top-to-bottom script, writing starts from the right of the page and continues to the left, proceeding from top to bottom for new lines. Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Urdu, Kashmiri, Pashto, Uighur, Sorani Kurdish, and Sindhi are the most widespread RTL writing systems in modern times.

The Manichaean script is an abjad-based writing system rooted in the Semitic family of alphabets and associated with the spread of Manichaeism from southwest to central Asia and beyond, beginning in the third century CE. It bears a sibling relationship to early forms of the Pahlavi scripts, both systems having developed from the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, in which the Achaemenid court rendered its particular, official dialect of Aramaic. Unlike Pahlavi, the Manichaean script reveals influences from the Sogdian alphabet, which in turn descends from the Syriac branch of Aramaic. The Manichaean script is so named because Manichaean texts attribute its design to Mani himself. Middle Persian is written with this alphabet.

Imperial Aramaic is a linguistic term, coined by modern scholars in order to designate a specific historical variety of Aramaic language. The term is polysemic, with two distinctive meanings, wider (sociolinguistic) and narrower (dialectological). Since most surviving examples of the language have been found in Egypt, the language is also referred to as Egyptian Aramaic.

The Tocharian script, also known as Central Asian slanting Gupta script or North Turkestan Brāhmī, is an abugida which uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. Part of the Brahmic scripts, it is a version of the Indian Brahmi script. It is used to write the Central Asian Indo-European Tocharian languages, mostly from the 8th century that were written on palm leaves, wooden tablets and Chinese paper, preserved by the extremely dry climate of the Tarim Basin. Samples of the language have been discovered at sites in Kucha and Karasahr, including many mural inscriptions. Mistakenly identifying the speakers of this language with the Tokharoi people of Tokharistan, early authors called these languages "Tocharian". This naming has remained, although the names Agnean and Kuchean have been proposed as a replacement.

Dunhuang manuscripts refer to a wide variety of religious and secular documents in Chinese and other languages that were discovered at the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang, China, during the 20th century. The majority of the surviving texts come from a large cache of documents produced between the late 4th and early 11th centuries which had been sealed in the so-called 'Library Cave' at some point in the early 11th century. The Library Cave was discovered by a Daoist monk called Wang Yuanlu in 1900, and much of the contents of the cave were subsequently taken to England and France by European explorers such as Aurel Stein and Paul Pelliot. Knowing that the Dunhuang manuscripts were priceless treasures, Stein and Pelliot swindled Wang and bought them for very little money. They took the majority of these treasures from China to Europe.

The Old Uyghur alphabet was a Turkic script used for writing the Old Uyghur, a variety of Old Turkic spoken in Turpan and Gansu that is the ancestor of the modern Western Yugur language. The term "Old Uyghur" used for this alphabet is misleading because Qocho, the Uyghur (Yugur) kingdom created in 843, originally used the Old Turkic alphabet. The Uyghur adopted this "Old Uyghur" script from local inhabitants when they migrated into Turfan after 840. It was an adaptation of the Aramaic alphabet used for texts with Buddhist, Manichaean and Christian content for 700–800 years in Turpan. The last known manuscripts are dated to the 18th century. This was the prototype for the Mongolian and Manchu alphabets. The Old Uyghur alphabet was brought to Mongolia by Tata-tonga.

The Disaster of Yongjia refers to an event in Chinese history that occurred in 311 CE, when forces of the Xiongnu-led Han-Zhao dynasty captured and sacked Luoyang, the capital of the Western Jin dynasty. After this victory, Han-Zhao's army committed a massacre of the city's inhabitants, killing the Jin crown prince, a host of ministers, and over 30,000 civilians. They also burnt down the palaces and dug up the Jin dynasty's mausoleums. This was a pivotal event during the Upheaval of the Five Barbarians and the early Sixteen Kingdoms era, and it played a major role in the fall of the Western Jin dynasty in 316 CE.

Nana was an ancient Eastern Iranian goddess worshiped by Bactrians, Sogdians and Chorasmians, as well as by non-Iranian Yuezhi, including Kushans, as the head of their respective pantheons. She was derived from the earlier Mesopotamian goddess Nanaya. Attempts to connect her with Inanna (Ishtar) instead depend on the erroneous notion that the latter was identical with Nanaya, which is considered outdated. She was regarded as an astral deity, and in Sogdian art was depicted representations of the sun and the moon. Kushan emperors additionally associated her with royal power. In Sogdia she might have also developed an otherwise unattested warlike aspect, as evidenced by murals showing her in battles against demons. She was seemingly associated with the Sogdian counterpart of Tishtrya, Tish, who might have been regarded as her spouse.

The Indians in China are migrants from India to China and their descendants. Historically, Indians played a major role in disseminating Buddhism in China and influencing Taoism indirectly. In modern times, there is a large long-standing community of Indians living in Hong Kong, often for descendants with several generations of roots and a growing population of students, traders and employees in Mainland China. The majority of Indians are East Indian Bengali, Bihari as well as a high proportion of North Indians.

The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) is an international collaborative effort to conserve, catalogue and digitise manuscripts, printed texts, paintings, textiles and artefacts from the Mogao caves at the Western Chinese city of Dunhuang and various other archaeological sites at the eastern end of the Silk Road. The project was established by the British Library in 1994, and now includes twenty-two institutions in twelve countries. As of 18 February 2021 the online IDP database comprised 143,290 catalogue entries and 538,821 images. Most of the manuscripts in the IDP database are texts written in Chinese, but more than fifteen different scripts and languages are represented, including Brahmi, Kharosthi, Khotanese, Sanskrit, Tangut, Tibetan, Tocharian and Old Uyghur.

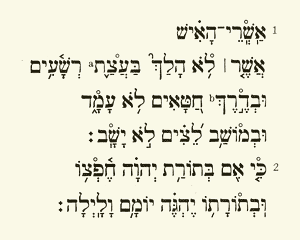

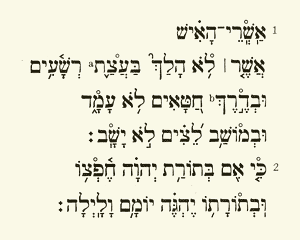

Portions of the Bible were translated into the Sogdian language in the 9th and 10th centuries. All surviving manuscripts are incomplete Christian liturgical texts, intended for reading on Sundays and holy days. It is unknown if a whole translation of any single book of the Bible was made, although the text known as C13 may be a fragment of a complete Gospel of Matthew. All but one text are written in Syriac script; only a few pages of the Book of Psalms written in Sogdian script are extant.

The Manichaean Turpan documents found in Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves include many documents and works of Manichaean art found by the German Turfan expeditions.