Trafalgar Square is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, established in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. The square's name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the British naval victory in the Napoleonic Wars over France and Spain that took place on 21st October 1805 off the coast of Cape Trafalgar.

George Vertue was an English engraver and antiquary, whose notebooks on British art of the first half of the 18th century are a valuable source for the period.

Grinling Gibbons was an Anglo-Dutch sculptor and wood carver known for his work in England, including Windsor Castle, the Royal Hospital Chelsea and Hampton Court Palace, St Paul's Cathedral and other London churches, Petworth House and other country houses, Trinity College, Oxford, and Trinity College, Cambridge. Gibbons was born to English parents in Holland, where he was educated.

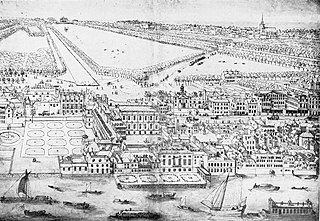

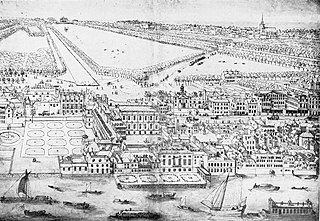

The Palace of Whitehall – also spelled White Hall – at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, with the notable exception of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. Henry VIII moved the royal residence to White Hall after the old royal apartments at the nearby Palace of Westminster were themselves destroyed by fire. Although the Whitehall palace has not survived, the area where it was located is still called Whitehall and has remained a centre of the British government.

Louis-François Roubiliac was a French sculptor who worked in England. One of the four most prominent sculptors in London working in the rococo style, he was described by Margaret Whinney as "probably the most accomplished sculptor ever to work in England".

Baroque sculpture is the sculpture associated with the Baroque style of the period between the early 17th and mid 18th centuries. In Baroque sculpture, groups of figures assumed new importance, and there was a dynamic movement and energy of human forms—they spiralled around an empty central vortex, or reached outwards into the surrounding space. Baroque sculpture often had multiple ideal viewing angles, and reflected a general continuation of the Renaissance move away from the relief to sculpture created in the round, and designed to be placed in the middle of a large space—elaborate fountains such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini‘s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, or those in the Gardens of Versailles were a Baroque speciality. The Baroque style was perfectly suited to sculpture, with Bernini the dominating figure of the age in works such as The Ecstasy of St Theresa (1647–1652). Much Baroque sculpture added extra-sculptural elements, for example, concealed lighting, or water fountains, or fused sculpture and architecture to create a transformative experience for the viewer. Artists saw themselves as in the classical tradition, but admired Hellenistic and later Roman sculpture, rather than that of the more "Classical" periods as they are seen today.

Artus Quellinus the Elder, Artus Quellinus I or Artus (Arnoldus) Quellijn was a Flemish sculptor. He is regarded as the most important representative of the Baroque in sculpture in the Southern Netherlands. He worked for a long period in the Dutch Republic and operated large workshops both in Antwerp and Amsterdam. His work had a major influence on the development of sculpture in Northern Europe.

Tobias Rustat was a courtier to King Charles II and a benefactor of the University of Cambridge. He is remembered for creating the first fund for the purchase of books at the Cambridge University Library. He was an investor in, and Assistant of, the Royal African Company, an English mercantile company involved in the slave trade.

John Bushnell (1636–1701) was an English sculptor, known for several outstanding funeral monuments in English churches including Westminster Abbey.

Peter van Dievoet was a Flemish Baroque sculptor, statuary, wood carver and designer of ornamental architectural elements active in Brussels and England. He is known for his work on a number of the Baroque guild houses on the Grand-Place, which was rebuilt after the bombardment of 1695, as well as on the Statue of James II on Trafalgar Square, London, made in collaboration with fellow Flemish sculptor Laurens van der Meulen. He was the half-brother of Philippe van Dievoet, goldsmith to King Louis XIV of France and the uncle of the Parisian printer Guillaume Vandive.

Nicholas Stone was an English sculptor and architect. In 1619 he was appointed master-mason to James I, and in 1626 to Charles I.

Philippe Mercier was an artist of French Huguenot descent from the German realm of Brandenburg-Prussia, usually defined to French school. Active in England for most of his working life, Mercier is considered one of the first practitioners of the Rococo style, and is credited with influencing a new generation of 18th-century English artists.

Johan Faber, anglicized as John Faber, commonly referred to as John Faber the Elder, was a Dutch miniaturist and portrait engraver active in London, where he set up a shop for producing and marketing his own work. His son John Faber the Younger was also active in this field.

The Privy Garden of the Palace of Whitehall was a large enclosed space in Westminster, London, that was originally a pleasure garden used by the late Tudor and Stuart monarchs of England. It was created under Henry VIII and was expanded and improved under his successors, but lost its royal patronage after the Palace of Whitehall was almost totally destroyed by fire in 1698.

Artus Quellinus III, known in England as Arnold Quellin was a Flemish sculptor who after training in Antwerp was mainly active in London. Here he worked in partnership with the English sculptor Grinling Gibbons on some commissions. Some of the works created during their partnership cannot with certainty be attributed to Quellinus or Gibbons. The drop in quality of the large-scale figurative works in the workshop of Gibbons following the early death of Quellinus has been seen as evidence of the heavy reliance on Quellinus to produce such works.

The statue of Charles II stands in the Figure, or Middle, Court of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, London. The sculptor was Grinling Gibbons, and the statue was executed around 1680–1682. The king founded the Royal Hospital in 1682 as a home for retired army veterans. The statue is a Grade I listed structure.

Laurens van der Meulen, also Laureys or Laurent van der Meulen, known in England as Laurence Vander Meulen (1643–1719), was a Flemish sculptor, painter and frame-maker who, after training in his native Mechelen, worked for some time in England. He is best known there for having created the statue of King James II now in Trafalgar Square, together with the Flemish sculptor Peter van Dievoet, while working in the workshop of Grinling Gibbons. He is also known for his wood carvings of frames and medallions.

The Van Dievoetfamily is a Belgian family originating from the Duchy of Brabant. It descends from the Seven Lineages of Brussels and its members have been bourgeois (freemen) of that city since the 1600s. It formed, at the end of the 17th century, a now extinct Parisian branch which used the name Vandive.

The Maison de l'Agneau Blanc or simply l'Agneau Blanc is a Baroque house, built in 1696, located at 42, rue du Marché aux Herbes/Grasmarkt in Brussels, Belgium, parallel to the Grand-Place/Grote Markt. It has been a protected heritage site since 2011.

A bronze equestrian statue of King Charles II on horseback sits in the Upper Ward of Windsor Castle beneath the castle's Round Tower. It was inspired by Hubert Le Sueur's statue of Charles I in London, the statue was cast by Josias Ibach in 1679, with the marble plinth featuring carvings by Grinling Gibbons. The statue was commissioned by Tobias Rustat, Charles's valet. Rustat was a significant philanthropist of the 1670s. Rustat's fortune was partially derived from the transatlantic slave trade, having been an investor in the Royal African Company.