The Diatessaron is the most prominent early gospel harmony. It was created in the Syriac language by Tatian, an Assyrian early Christian apologist and ascetic. Tatian sought to combine all the textual material he found in the four gospels - Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John - into a single coherent narrative of Jesus's life and death. However, and in contradistinction to most later gospel harmonists, Tatian appears not to have been motivated by any aspiration to validate the four separate canonical gospel accounts; or to demonstrate that, as they stood, they could each be shown as being without inconsistency or error.

Tatian of Adiabene, or Tatian the Syrian or Tatian the Assyrian, was an Assyrian Christian writer and theologian of the 2nd century.

The Peshitta is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition, including the Maronite Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Malabar Independent Syrian Church, the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East and the Syro-Malabar Church.

George Mamishisho Lamsa was an Assyrian author. He was born in Mar Bishu in what is now the extreme east of Turkey. A native Aramaic speaker, he translated the Aramaic Peshitta Old and New Testaments into English. He popularized the claim of the Assyrian Church of the East that the New Testament was written in Aramaic and then translated into Greek, contrary to academic consensus.

The Aramaic original New Testament theory is the belief that the Christian New Testament was originally written in Aramaic.

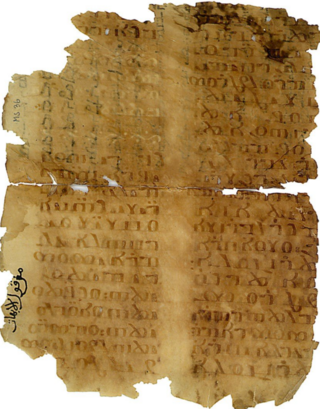

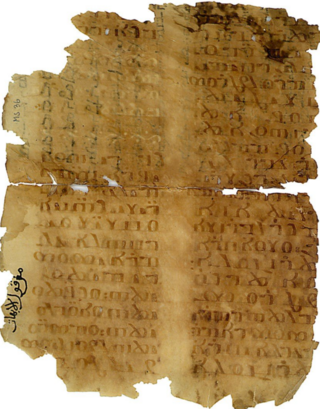

The Syriac Sinaiticus or Codex Sinaiticus Syriacus (syrs), known also as the Sinaitic Palimpsest, of Saint Catherine's Monastery, or Old Syriac Gospels is a late-4th- or early-5th-century manuscript of 179 folios, containing a nearly complete translation of the four canonical Gospels of the New Testament into Syriac, which have been overwritten by a vita (biography) of female saints and martyrs with a date corresponding to AD 697. This palimpsest is the oldest copy of the Gospels in Syriac, one of two surviving manuscripts that are conventionally dated to before the Peshitta, the standard Syriac translation.

Syriac literature is literature in the Syriac language. It is a tradition going back to the Late Antiquity. It is strongly associated with Syriac Christianity.

A biblical manuscript is any handwritten copy of a portion of the text of the Bible. Biblical manuscripts vary in size from tiny scrolls containing individual verses of the Jewish scriptures to huge polyglot codices containing both the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and the New Testament, as well as extracanonical works.

The Curetonian Gospels, designated by the siglum syrcur, are contained in a manuscript of the four gospels of the New Testament in Old Syriac. Together with the Sinaiticus Palimpsest the Curetonian Gospels form the Old Syriac Version, and are known as the Evangelion Dampharshe in the Syriac Orthodox Church.

Christian Palestinian Aramaic was a Western Aramaic dialect used by the Melkite Christian community, predominantly of Jewish descent, in Palestine, Transjordan and Sinai between the fifth and thirteenth centuries. It is preserved in inscriptions, manuscripts and amulets. All the medieval Western Aramaic dialects are defined by religious community. CPA is closely related to its counterparts, Jewish Palestinian Aramaic (JPA) and Samaritan Aramaic (SA). CPA shows a specific vocabulary that is often not paralleled in the adjacent Western Aramaic dialects.

Agnes Smith Lewis (1843–1926) and Margaret Dunlop Gibson (1843–1920), nées Smith, were English Semitic scholars and travellers. As the twin daughters of John Smith of Irvine, Ayrshire, Scotland, they learned more than 12 languages between them, specialising in Arabic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic, and Syriac, and became acclaimed scholars in their academic fields, and benefactors to the Presbyterian Church of England, especially to Westminster College, Cambridge.

Bible translations into Aramaic covers both Jewish translations into Aramaic (Targum) and Christian translations into Aramaic, also called Syriac (Peshitta).

Dura Parchment 24, designated as Uncial 0212, is a Greek uncial manuscript of the New Testament. The manuscript has been assigned to the 3rd century, palaeographically, though an earlier date cannot be excluded. It contains some unusual orthographic features, which have been found nowhere else.

Codex Climaci rescriptus is a collective palimpsest manuscript consisting of several individual manuscripts underneath, Christian Palestinian Aramaic texts of the Old and New Testament as well as two apocryphal texts, including the Dormition of the Mother of God, and is known as Uncial 0250 with a Greek uncial text of the New Testament and overwritten by Syriac treatises of Johannes Climacus : the scala paradisi and the liber ad pastorem. Paleographically the Greek text has been assigned to the 7th or 8th century, and the Aramaic text to the 6th century. It originates from Saint Catherine's Monastery going by the New Finds of 1975. Formerly it was classified for CCR 5 and CCR 6 as lectionary manuscript, with Gregory giving the number ℓ 1561 to it.

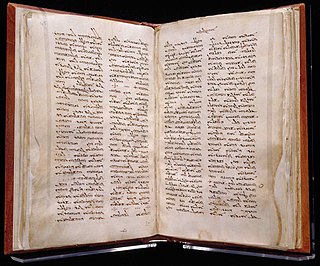

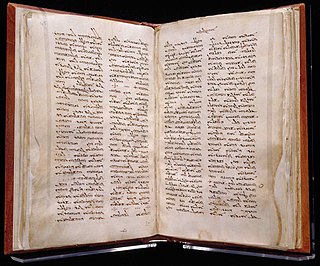

Codex Phillipps 1388, Syriac manuscript of the New Testament, on parchment. It contains the text of the four Gospels. Palaeographically it had been assigned to the 5th/6th centuries. It is one of the oldest manuscripts of Peshitta with some Old Syriac readings.

British Library, Add MS 14459, Syriac manuscript of the New Testament, on a parchment. It is dated by a colophon to the year 528-529 or 537-538. It is one of the oldest manuscript of Peshitta and the earliest dated manuscript containing two of the Gospels in Syriac. The manuscript is bound with another dated to the 5th century.

The León Palimpsest, designated l or 67, is a 7th-century Latin manuscript pandect of the Christian Bible conserved in the cathedral of León, Spain. The text, written on vellum, is in a fragmentary condition. In some parts it represents the Old Latin version, while following Jerome's Vulgate in others. The codex is a palimpsest.

The Crawford Aramaic New Testament manuscript is a 12th-century Aramaic manuscript containing 27 books of the New Testament. This manuscript is notable because its final book, the Book of Revelation, is the sole surviving manuscript of any Aramaic (Syriac) version of the otherwise missing Book of Revelation from the Peshitta Syriac New Testament. Five books were translated into Syriac later for the Harklean New Testament.

Early translations of the New Testament – translations of the New Testament created in the 1st millennium. Among them, the ancient translations are highly regarded. They play a crucial role in modern criticism of New Testament's text. These translations reached the hands of scholars in copies and also underwent changes, but the subsequent history of their text was independent of the Greek text-type and are therefore helpful in reconstructing it. Three of them – Syriac, Latin, Coptic – date from the late 2nd century and are older than the surviving full Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. They were written before the first revisions of the Greek New Testament and are therefore the most highly regarded. They are obligatorily cited in all critical editions of the Greek text-type. Translations produced after 300 are already dependent on the reviews, but are nevertheless important and are generally cited in the critical apparatus. The Gothic and Slavic translations are rarely cited in critical editions. Omitted are those of the translations of the first millennium that were not translated directly from the Greek original, but based on another translation.