Gelert is a legendary wolfhound associated with the village of Beddgelert in Gwynedd, north-west Wales. In the legend, Llywelyn the Great returns from hunting to find his baby missing, the cradle overturned, and Gelert with a blood-smeared mouth. Believing the dog had devoured the child, Llywelyn draws his sword and kills Gelert. After the dog's dying yelp, Llywelyn hears the cries of the baby, unharmed under the cradle, along with a dead wolf which had attacked the child and been killed by Gelert. Llywelyn is overcome with remorse and buries the dog with great ceremony, but can still hear its dying yelp. After that day, Llywelyn never smiles again.

The "Town Musicians of Bremen" is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm and published in Grimms' Fairy Tales in 1819.

The Panchatantra is an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose, arranged within a frame story. The surviving work is dated to about 200 BCE, but the fables are likely much more ancient. The text's author is unknown, but it has been attributed to Vishnu Sharma in some recensions and Vasubhaga in others, both of which may be fictitious pen names. It is likely a Hindu text, and based on older oral traditions with "animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine".

"The Frog Prince; or, Iron Henry" is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in Grimm's Fairy Tales. Traditionally, it is the first story in their folktale collection. The tale is classified as Aarne-Thompson type 440.

The Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index is a catalogue of folktale types used in folklore studies. The ATU Index is the product of a series of revisions and expansions by an international group of scholars: originally composed in German by Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne (1910), the index was translated into English, revised, and expanded by American folklorist Stith Thompson, and later further revised and expanded by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther (2004). The ATU Index, along with Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932)—with which it is used in tandem—is an essential tool for folklorists.

The Seven Wise Masters is a cycle of stories of Sanskrit, Persian or Hebrew origins.

The Deer without a Heart is an ancient fable, attributed to Aesop in Europe and numbered 336 in the Perry Index. It involves a deer who was twice persuaded by a wily fox to visit the ailing lion. After the lion had killed it, the fox stole and ate the deer's heart. When asked where it is, the fox reasoned that an animal so foolish as to visit a lion in his den cannot have had one, an argument that reflects the ancient belief that the heart was the seat of thoughts and intellect. The story is catalogued as type 52 in the Aarne-Thompson classification system.

The Kathāsaritsāgara is a famous 11th-century collection of Indian legends, histories and folk tales as retold in Sanskrit by the Shaivite Somadeva.

The Heart of a Monkey is a Swahili fairy tale collected by Edward Steere in Swahili Tales. Andrew Lang included it in The Lilac Fairy Book. It is Aarne-Thompson 91.

The Choking Doberman is an urban legend that originated in the United States. The story involves a protective pet found by its owner gagging on human fingers lodged in its throat. As the story unfolds, the dog's owner discovers an intruder whose hand is bleeding from the dog bite.

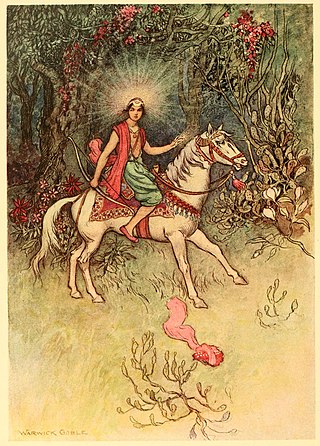

The Snake Prince is an Indian fairy tale, a Punjabi story collected by Major Campbell in Feroshepore. Andrew Lang included it in The Olive Fairy Book (1907).

Ramsay Wood is the author of two sui generis modern novels which aim – via vernacular spiels within complex frame-story narratives – to popularize the pre-literate, oral story-listening drama of multicultural animal fables mimed and declaimed along the ancient Silk Road. His books blend The Jatakas Tales, The Panchatantra and the likely role of Alexander the Great's legacy in "bringing the Aesopian tradition to North India and Central Asia" via Hellenization in Central Asia and India. Wood's Kalila and Dimna – Selected Fables of Bidpai was published by Knopf in 1980 with an Introduction by Nobel laureate Doris Lessing.

In a cumulative tale, sometimes also called a chain tale, action or dialogue repeats and builds up in some way as the tale progresses. With only the sparest of plots, these tales often depend upon repetition and rhythm for their effect, and can require a skilled storyteller to negotiate their tongue-twisting repetitions in performance. The climax is sometimes abrupt and sobering as in "The Gingerbread Man." The device often takes the form of a cumulative song or nursery rhyme. Many cumulative tales feature a series of animals or forces of nature each more powerful than the last.

Saint Gelert, also known as Celer, Celert or Kellarth, was an early Celtic saint. Several locations in Wales are believed to bear his name. They include Beddgelert and the surrounding Gelert Valley and Llangeler where there is a church dedicated to him. Through the promotional efforts of an innkeeper in the early 1790s, St. Gelert, the human, has become much conflated with the legend of a saintly dog putatively from the same region, Gelert.

The Tiger, the Brahmin and the Jackal is a popular Indian folklore with a long history and many variants. The earliest record of the folklore was included in the Panchatantra, which dates the story between 200 BCE and 300 CE.

The Mouse Turned into a Maid is an ancient fable of Indian origin that travelled westwards to Europe during the Middle Ages and also exists in the Far East. The story is Aarne-Thompson type 2031C in his list of cumulative tales, another example of which is The Husband of the Rat's Daughter. It concerns a search for a partner through a succession of more powerful forces, resolved only by choosing an equal.

Princess Himal and Nagaray or Himal and Nagrai is a very popular Kashmiri folktale about the love between a human princess and a Naga (snake-like) prince. The story is well-known in the region and has many renditions. One version of the story was collected by British reverend James Hinton Knowles and published in his book Folk-Tales of Kashmir.

The Boy with a Moon on his Forehead is a Bengali folktale collected by Maive Stokes and Lal Behari Day.

The Man and the Girl at the Underground Mansion is a Danish folktale collected by theologue Nikolaj Christensen in the 19th century, but published in the 20th century by Danish folklorist Laurits Bodker.