Samuel Taylor Coleridge was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets. He also shared volumes and collaborated with Charles Lamb, Robert Southey, and Charles Lloyd.

William Wordsworth was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication Lyrical Ballads (1798).

Robert Southey was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a radical but became steadily more conservative as he gained respect for Britain and its institutions. Other romantics such as Byron accused him of siding with the establishment for money and status. He is remembered especially for the poem "After Blenheim" and the original version of "Goldilocks and the Three Bears".

Walter Savage Landor was an English writer, poet, and activist. His best known works were the prose Imaginary Conversations, and the poem "Rose Aylmer," but the critical acclaim he received from contemporary poets and reviewers was not matched by public popularity. As remarkable as his work was, it was equalled by his rumbustious character and lively temperament. Both his writing and political activism, such as his support for Lajos Kossuth and Giuseppe Garibaldi, were imbued with his passion for liberal and republican causes. He befriended and influenced the next generation of literary reformers such as Charles Dickens and Robert Browning.

Caroline Anne Southey was an English poet and painter. She became the second wife of the poet Robert Southey, a prominent writer at the time.

"The Idiot Boy" is a poem written by William Wordsworth, a representative of the Romantic movement in English literature. The poem was composed in spring 1798 and first published in the same year in Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems written by Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, which is considered to be a turning point in the history of English literature and the Romantic movement. The poem investigates such themes as language, intellectual disability, maternity, emotionality, organisation of experience and "transgression of the natural."

The Lake Poets were a group of English poets who all lived in the Lake District of England, United Kingdom, in the first half of the nineteenth century. As a group, they followed no single "school" of thought or literary practice then known. They were named, only to be uniformly disparaged, by the Edinburgh Review. They are considered part of the Romantic Movement.

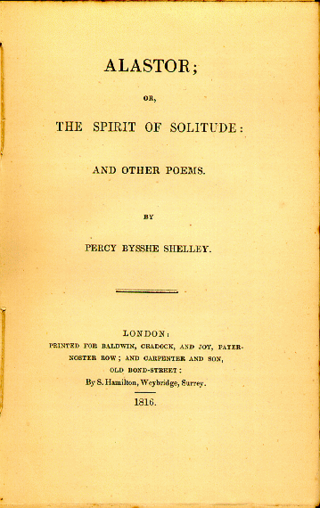

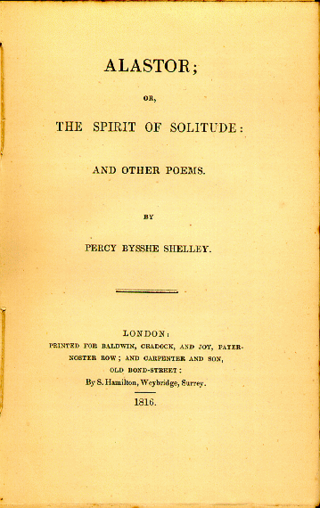

Alastor, or The Spirit of Solitude is a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley, written from 10 September to 14 December in 1815 in Bishopsgate, near Windsor Great Park and first published in 1816. The poem was without a title when Shelley passed it along to his contemporary and friend Thomas Love Peacock. The poem is 720 lines long. It is considered to be one of the first of Shelley's major poems.

— From Cantos 27 and 56, In Memoriam A.H.H., by Alfred Tennyson, published this year

"Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood" is a poem by William Wordsworth, completed in 1804 and published in Poems, in Two Volumes (1807). The poem was completed in two parts, with the first four stanzas written among a series of poems composed in 1802 about childhood. The first part of the poem was completed on 27 March 1802 and a copy was provided to Wordsworth's friend and fellow poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who responded with his own poem, "Dejection: An Ode", in April. The fourth stanza of the ode ends with a question, and Wordsworth was finally able to answer it with seven additional stanzas completed in early 1804. It was first printed as "Ode" in 1807, and it was not until 1815 that it was edited and reworked to the version that is currently known, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality".

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was born on 21 October 1772. The youngest of 14 children, he was educated after his father's death and excelled in classics. He attended Christ's Hospital and Jesus College, Cambridge. While attending college, he befriended two other Romanticists, Charles Lamb and Robert Southey, the latter causing him to eventually drop out of college and pursue both poetic and political ambitions.

Sordello is a narrative poem by the English poet Robert Browning. Worked on for seven years, and largely written between 1836 and 1840, it was published in March 1840. It consists of a fictionalised version of the life of Sordello da Goito, a 13th-century Lombard troubadour depicted in Canto VI of Dante Alighieri's Purgatorio.

Madoc is an 1805 epic poem composed by Robert Southey. It is based on the legend of Madoc, a supposed Welsh prince who fled internecine conflict and sailed to America in the 12th century. The origins of the poem can be traced to Southey's schoolboy days when he completed a prose version of Madoc's story. By the time Southey was in his twenties, he began to devote himself to working on the poem in hopes that he could sell it to raise money to fulfill his ambitions to start a new life in America, where he hoped to found Utopian commune or "Pantisocracy". Southey finally completed the poem as a whole in 1799, at the age of 25. However, he began to devote his efforts into extensively editing the work, and Madoc was not ready for publication until 1805. It was finally published in two volumes by the London publisher Longman with extensive footnotes.

The Curse of Kehama is an 1810 epic poem composed by Robert Southey. The origins of the poem can be traced to Southey's schoolboy days when he suffered from insomnia, along with his memories of a dark and mysterious schoolmate that later formed the basis for one of the poem's villains. The poem was started in 1802 following the publication of Southey's epic Thalaba the Destroyer. After giving up on the poem for a few years, he returned to it after prompting by the poet Walter Savage Landor encouraged him to complete his work. When it was finally published, it sold more copies than his previous works.

Roderick the Last of the Goths is an 1814 epic poem composed by Robert Southey. The origins of the poem lie in Southey's wanting to write a poem describing Spain and the story of Rodrigo. Originally entitled "Pelayo, the Restorer of Spain," the poem was later retitled to reflect the change of emphasis within the story. It was completed after Southey witnessed Napoleon's actions in Europe, and Southey included his reactions against invading armies into the poem. The poem was successful, and multiple editions followed immediately after the first edition.

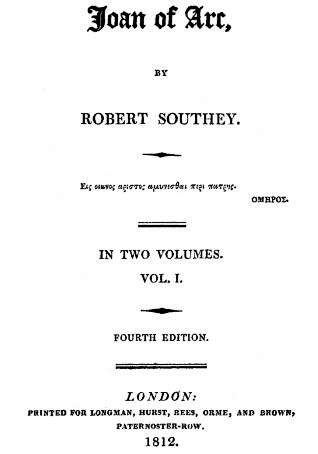

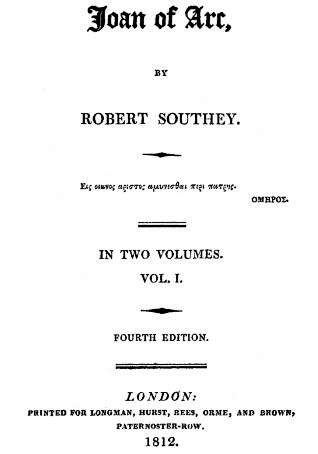

Joan of Arc is a 1796 epic poem composed by Robert Southey. The idea for the story came from a discussion between Southey and Grosvenor Bedford, when Southey realised that the story would be suitable for an epic. The subject further appealed to Southey because the events of the French Revolution were concurrent to the writing of the poem and would serve as a parallel to current events. Eventually, Samuel Taylor Coleridge helped rewrite parts of the poem for a 1798 edition. Later editions removed Coleridge's additions along with other changes.

The Feast of the Poets is a poem by Leigh Hunt that was originally published in 1811 in the Reflector. It was published in an expanded form in 1814, and revised and expanded throughout his life. The work describes Hunt's contemporary poets, and either praises or mocks them by allowing only the best to dine with Apollo. The work also provided commentary on William Wordsworth and Romantic poetry. Critics praised or attacked the work on the basis of their sympathies towards Hunt's political views.

The Vision of Judgment (1822) is a satirical poem in ottava rima by Lord Byron, which depicts a dispute in Heaven over the fate of George III's soul. It was written in response to the Poet Laureate Robert Southey's A Vision of Judgement (1821), which had imagined the soul of king George triumphantly entering Heaven to receive his due. Byron was provoked by the High Tory point of view from which the poem was written, and he took personally Southey's preface which had attacked those "Men of diseased hearts and depraved imaginations" who had set up a "Satanic school" of poetry, "characterized by a Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety". He responded in the preface to his own Vision of Judgment with an attack on "The gross flattery, the dull impudence, the renegado intolerance, and impious cant, of the poem", and mischievously referred to Southey as "the author of Wat Tyler", an anti-royalist work from Southey's firebrand revolutionary youth. His parody of A Vision of Judgement was so lastingly successful that, as the critic Geoffrey Carnall wrote, "Southey's reputation has never recovered from Byron's ridicule."

Robert Anderson (1770–1833), was an English labouring class poet from Carlisle. He was best known for his ballad-style poems in Cumbrian dialect.

"Man Was Made to Mourn: A Dirge" is a dirge of eleven stanzas by the Scots poet Robert Burns, first published in 1784 and included in the first edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect in 1786. The poem is one of Burns's many early works that criticize class inequalities. It is known for its line protesting "Man's inhumanity to man", which has been widely quoted since its publication.