Geoffrey Chaucer was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for The Canterbury Tales. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He was the first writer to be buried in what has since come to be called Poets' Corner, in Westminster Abbey. Chaucer also gained fame as a philosopher and astronomer, composing the scientific A Treatise on the Astrolabe for his 10-year-old son Lewis. He maintained a career in the civil service as a bureaucrat, courtier, diplomat, and member of parliament.

Piers Plowman or Visio Willelmi de Petro Ploughman is a Middle English allegorical narrative poem by William Langland. It is written in un-rhymed, alliterative verse divided into sections called passus.

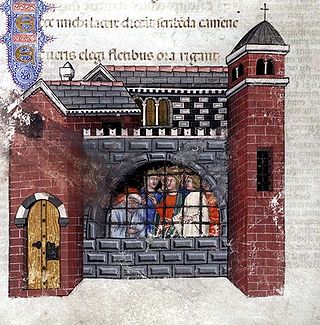

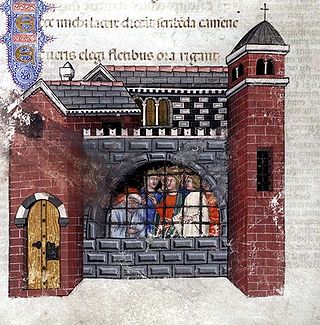

Le Roman de la Rose is a medieval poem written in Old French and presented as an allegorical dream vision. As poetry, The Romance of the Rose is a notable instance of courtly literature, purporting to provide a "mirror of love" in which the whole art of romantic love is disclosed. Its two authors conceived it as a psychological allegory; throughout the Lover's quest, the word Rose is used both as the name of the titular lady and as an abstract symbol of female sexuality. The names of the other characters function both as personal names and as metonyms illustrating the different factors that lead to and constitute a love affair. Its long-lasting influence is evident in the number of surviving manuscripts of the work, in the many translations and imitations it inspired, and in the praise and controversy it inspired.

Rhyme royal is a rhyming stanza form that was introduced to English poetry by Geoffrey Chaucer. The form enjoyed significant success in the fifteenth century and into the sixteenth century. It has had a more subdued but continuing influence on English verse in more recent centuries.

John Lydgate of Bury was an English monk and poet, born in Lidgate, near Haverhill, Suffolk, England.

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages. The literature of this time was composed of religious writings as well as secular works. Just as in modern literature, it is a complex and rich field of study, from the utterly sacred to the exuberantly profane, touching all points in-between. Works of literature are often grouped by place of origin, language, and genre.

The Parlement of Foules, also called the Parlement of Briddes or the Assemble of Foules, is a poem by Geoffrey Chaucer made up of approximately 700 lines. The poem, which is in the form of a dream vision in rhyme royal stanza, contains one of the earliest references to the idea that St. Valentine's Day is a special day for lovers.

The Book of the Duchess, also known as The Deth of Blaunche, is the earliest of Chaucer's major poems, preceded only by his short poem, "An ABC", and possibly by his translation of The Romaunt of the Rose. Based on the themes and title of the poem, most sources put the date of composition after 12 September 1368 and before 1372, with many recent studies privileging a date as early as the end of 1368.

Guillaume de Lorris was a French scholar and poet from Lorris. He was the author of the first section of the Roman de la Rose. Little is known about him, other than that he wrote the earlier section of the poem around 1230, and that the work was completed forty years later by Jean de Meun. He is only known by mention of Jean de Meun,, in Roman de la Rose.

Jean de Meun was a French author best known for his continuation of the Roman de la Rose.

Tail rhyme is a family of stanzaic verse forms used in poetry in French and especially English during and since the Middle Ages, and probably derived from models in medieval Latin versification.

Medieval French literature is, for the purpose of this article, Medieval literature written in Oïl languages during the period from the eleventh century to the end of the fifteenth century.

A dream vision or visio is a literary device in which a dream or vision is recounted as having revealed knowledge or a truth that is not available to the dreamer or visionary in a normal waking state. While dreams occur frequently throughout the history of literature, visionary literature as a genre began to flourish suddenly, and is especially characteristic in early medieval Europe. In both its ancient and medieval form, the dream vision is often felt to be of divine origin. The genre reemerged in the era of Romanticism, when dreams were regarded as creative gateways to imaginative possibilities beyond rational calculation.

Sir Richard Ros, was an English poet, the son of Sir Thomas Ros, lord of Hamlake (Helmsley) in Yorkshire and of Belvoir in Leicestershire.

The Pilgrim's Tale is an English anti-monastic poem. It was probably written ca. 1536–38, since it makes references to events in 1534 and 1536 – e.g. the Lincolnshire Rebellion – and borrows from The Plowman's Tale and the 1532 text by William Thynne of Chaucer's Romaunt of the Rose, which is cited by page and line. It remains the most mysterious of the pseudo-Chaucerian texts. In his 1602 edition of the Works of Chaucer, Thomas Speght mentions that he hoped to find this elusive text. A prefatory advertisement to the reader in the 1687 edition of the Works speaks of an exhaustive search for The Pilgrim's Tale, which had proved fruitless

Chanticleer and the Fox is a fable that dates from the Middle Ages. Though it can be compared to Aesop's fable of The Fox and the Crow, it is of more recent origin. The story became well known in Europe because of its connection with several popular literary works and was eventually recorded in collections of Aesop's Fables from the time of Heinrich Steinhowel and William Caxton onwards. It is numbered 562 in the Perry Index.

Chaucer's influence on 15th-century Scottish literature began towards the beginning of the century with King James I of Scotland. This first phase of Scottish "Chaucerianism" was followed by a second phase, comprising the works of Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, and Gavin Douglas. At this point, England has recognised Scotland as an independent state following the end of the Wars of Scottish Independence in 1357. Because of Scottish history and the English’s recent involvement in that history, all of these writers are familiar with the works of Geoffrey Chaucer.

Hein van Aken, also called Hendrik van Aken or van Haken, was the parish priest in Korbeek-Lo, between Leuven and Brussels. He was born in Brussels, probably in the thirteenth century. He translated the Roman de la Rose by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun to Dutch, with the title Het Bouc van der Rosen,. Hein's translation, also commonly called Die Rose, was widespread. This is notable due to the many manuscripts and excerpts that are still preserved, for example in the University Library of Ghent. He is probably also the poet of a Dutch reworking of the French Ordene de chevalerie. With less reason, some also attribute the Natuurkunde van het Geheel-al to him, but a poem by him must be kept in the Comburger manuscript.

The Floure and the Leafe is an anonymous Middle English allegorical poem in 595 lines of rhyme royal, written around 1470. During the 17th, 18th, and most of the 19th century it was mistakenly believed to be the work of Geoffrey Chaucer, and was generally considered to be one of his finest poems. The name of the author is not known but the poem presents itself as the work of a woman, and some critics are inclined to take this at face value. The poet was certainly well-read, there being a number of echoes of earlier writers in the poem, including Geoffrey Chaucer, John Lydgate, John Gower, Andreas Capellanus, Guillaume de Lorris, Guillaume de Machaut, Jean Froissart, Eustache Deschamps, Christine de Pizan, and the authors of the "Lai du Trot" and the Kingis Quair.

Nicole de Margival was an Old French poet active around 1300. His two known works are Le Dit de la panthère d'amours and Les trois mors et les trois vis.