Philip Melanchthon was a German Christian Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, an intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and John Calvin as a reformer, theologian, and shaper of Protestantism.

The Cloud of Unknowing is an anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century. The text is a spiritual guide on contemplative prayer in the Late Middle Ages. The underlying message of this work suggests that the way to know God is to abandon consideration of God's particular activities and attributes, and be courageous enough to surrender one's mind and ego to the realm of "unknowing", at which point one may begin to glimpse the nature of God.

Andreas Osiander was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

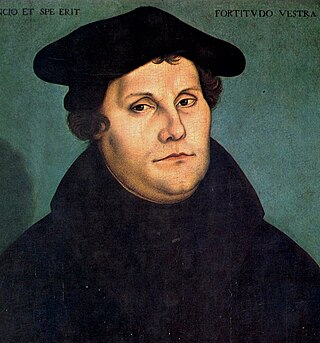

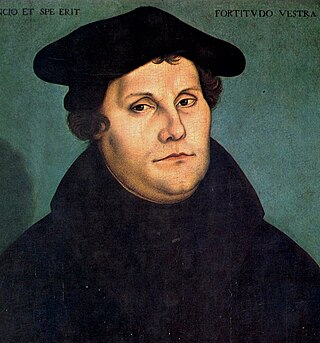

Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church was the second of the three major treatises published by Martin Luther in 1520, coming after the Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation and before On the Freedom of a Christian. The book-length work was theological, and as such was published in Latin as well as German, the language in which the treatises were written.

John van Ruysbroeck, original Flemish name Jan van Ruusbroec was an Augustinian canon and one of the most important of the Flemish mystics. Some of his main literary works include The Kingdom of the Divine Lovers, The Twelve Beguines, The Spiritual Espousals, A Mirror of Eternal Blessedness, The Little Book of Enlightenment, and The Sparkling Stone. Some of his letters also survive, as well as several short sayings. He wrote in the Dutch vernacular, the language of the common people of the Low Countries, rather than in Latin, the language of the Catholic Church liturgy and official texts, in order to reach a wider audience.

Richard Rolle was an English hermit, mystic, and religious writer. He is also known as Richard Rolle of Hampole or de Hampole, since at the end of his life he lived near a Cistercian nunnery in Hampole, now in South Yorkshire. In the words of Nicholas Watson, scholarly research has shown that "[d]uring the fifteenth century he was one of the most widely read of English writers, whose works survive in nearly four hundred English ... and at least seventy Continental manuscripts, almost all written between 1390 and 1500."

Catherine Winkworth was an English hymnwriter and educator. She translated the German chorale tradition of church hymns for English speakers, for which she is recognized in the calendar of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. She also worked for wider educational opportunities for girls, and translated biographies of two founders of religious sisterhoods. When 16, Winkworth appears to have coined a once well-known political pun, peccavi, "I have Sindh", relating to the British occupation of Sindh in colonial India.

The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of Calvinist churches, especially in Switzerland.

Ludwig Haetzer was an Anabaptist.

Johannes Tauler OP was a German mystic, a Roman Catholic priest and a theologian. A disciple of Meister Eckhart, he belonged to the Dominican order. Tauler was known as one of the most important Rhineland mystics. He promoted a certain neo-platonist dimension in the Dominican spirituality of his time.

Henry Suso, OP was a German Dominican friar and the most popular vernacular writer of the fourteenth century. Suso is thought to have been born on 21 March 1295. An important author in both Latin and Middle High German, he is also notable for defending Meister Eckhart's legacy after Eckhart was posthumously condemned for heresy in 1329. He died in Ulm on 25 January 1366, and was beatified by the Catholic Church in 1831.

Protestant Reformers were theologians whose careers, works and actions brought about the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century.

The Friends of God was a medieval mystical group of both ecclesiastical and lay persons within the Catholic Church and a center of German mysticism. It was founded between 1339 and 1343 during the Avignon Papacy of the Western Schism, a time of great turmoil for the Catholic Church. The Friends of God were originally centered in Basel, Switzerland and were also fairly important in Strasbourg and Cologne. Some late-nineteenth century writers made large claims for the movement, seeing it both as influential in fourteenth-century mysticism and as a precursor of the Protestant Reformation. Modern studies of the movement have emphasised the derivative and often second-rate character of its mystical literature, and its limited impact on medieval literature in Germany. Some of the movement's ideas still prefigured the Protestant reformation.

The theology of the Cross or staurology is a term coined by the German theologian Martin Luther to refer to theology that posits “the cross” as the only source of knowledge concerning who God is and how God saves. It is contrasted with the Theology of Glory, which places greater emphasis on human abilities and human reason.

Hans Denck was a German theologian and Anabaptist leader during the Reformation.

Bartholomaeus Arnoldi, OSA was an Augustinian friar and doctor of divinity who taught Martin Luther and later turned into his earliest and one of his personally closest opponents.

Eckhart von Hochheim, commonly known as Meister Eckhart, Master Eckhart or Eckehart, claimed original name Johannes Eckhart, was a German Catholic theologian, philosopher and mystic, born near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia in the Holy Roman Empire.

"Christ the Lord Is Risen Again!" is a German Christian hymn published by Michael Weiße in 1531 based on an earlier German hymn of a very similar name. It was translated into English in 1858 by Catherine Winkworth.

Susanna Winkworth was an English translator and philanthropist, elder sister of translator Catherine Winkworth.

Classics of Western Spirituality [CWS] is an English-language book series published by Paulist Press since 1978, which offers a library of historical texts on Christian spirituality as well as a representative selection of works on Jewish, Islamic, Sufi and Native American spirituality. Each volume is selected and translated by one or more scholars or spiritual leaders, with scholarly introductions and bibliographies of both primary and secondary materials. The series contains multiple genres of spiritual writing, including poems, songs, essays, theological treatises, meditations, mystical biographies, and philosophical investigations, and features works by famous authors such as Augustine of Hippo and Martin Luther. As well as lesser-known authors such as Maximus the Confessor and Moses de León.