Year 547 (DXLVII) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 547 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly popular in the Ancient Roman world.

Byzantine architecture is the architecture of the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, usually dated from 330 AD, when Constantine the Great established a new Roman capital in Byzantium, which became Constantinople, until the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. There was initially no hard line between the Byzantine and Roman Empires, and early Byzantine architecture is stylistically and structurally indistinguishable from late Roman architecture. The style continued to be based on arches, vaults and domes, often on a large scale. Wall mosaics with gold backgrounds became standard for the grandest buildings, with frescos a cheaper alternative.

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of western Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

A cathedra is the raised throne of a bishop in the early Christian basilica. When used with this meaning, it may also be called the bishop's throne. With time, the related term cathedral became synonymous with the "seat", or principal church, of a bishopric.

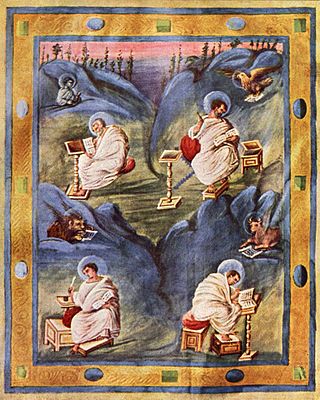

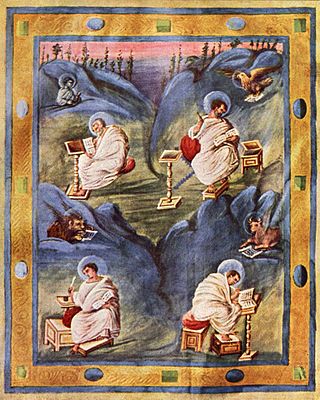

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

The Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo is a basilica church in Ravenna, Italy. It was erected by the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great as his palace chapel during the first quarter of the 6th century. This Arian church was originally dedicated in 504 AD to "Christ the Redeemer".

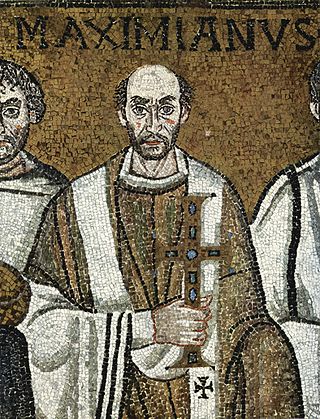

The Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe is a church in Classe, Ravenna, Italy, consecrated on 9 May 549 by the bishop Maximian and dedicated to Saint Apollinaris, the first bishop of Ravenna and Classe.

The Arian Baptistry in Ravenna, Italy is a Christian baptismal building that was erected by the Ostrogothic King Theodoric the Great between the end of the 5th century and the beginning of the 6th century A.D., at the same time as the Basilica of Sant' Apollinare Nuovo.

The Basilica of San Vitale is a late antique church in Ravenna, Italy. The sixth-century church is an important surviving example of early Byzantine art and architecture, and its mosaics in particular are some of the most-studied works in Byzantine art. It is one of eight structures in Ravenna inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Its foundational inscription describes the church as a basilica, though its centrally-planned design is not typical of the basilica form. Within the Roman Catholic Church it holds the honorific title of basilica for its historic and ecclesial importance.

Ivory carving is the carving of ivory, that is to say animal tooth or tusk, generally by using sharp cutting tools, either mechanically or manually. Objects carved in ivory are often called "ivories".

The Barberini ivory is a Byzantine ivory leaf from an imperial diptych dating from Late Antiquity, now in the Louvre in Paris. It represents the emperor as triumphant victor. It is generally dated from the first half of the 6th century and is attributed to an imperial workshop in Constantinople, while the emperor is usually identified as Justinian, or possibly Anastasius I or Zeno. It is a notable historical document because it is linked to queen Brunhilda of Austrasia. On the back there is a list of names of Frankish kings, all relatives of Brunhilda, indicating her important position. Brunhilda ordered the list to be inscribed and offered it to the church as a votive image.

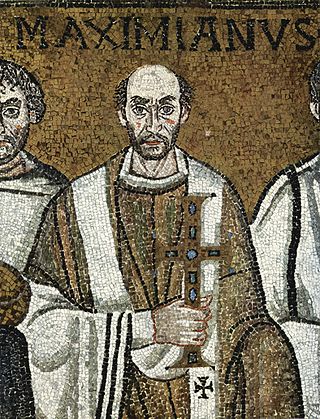

Maximianus of Ravenna, or Maximian was bishop of Ravenna in Italy. Ravenna was then the capital of the Byzantine Empire's territories in Italy, and Maximianus's role may have included secular political functions.

The Archiepiscopal Museum is located in Ravenna, Italy, next to the Baptistry of Neon and behind the Duomo of Ravenna. In the museum relics of early Christian Ravenna are preserved, including fragments of mosaic from the first cathedral church, and the chapel of Sant'Andrea, dating from the Gothic kingdom.

The Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus is a marble Early Christian sarcophagus used for the burial of Junius Bassus, who died in 359. It has been described as "probably the single most famous piece of early Christian relief sculpture." The sarcophagus was originally placed in or under Old St. Peter's Basilica, was rediscovered in 1597, and is now below the modern basilica in the Museo Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro in the Vatican. The base is approximately 4 x 8 x 4 feet.

Italy has the richest concentration of Late Antique and medieval mosaics in the world. Although the art style is especially associated with Byzantine art and many Italian mosaics were probably made by imported Greek-speaking artists and craftsmen, there are surprisingly few significant mosaics remaining in the core Byzantine territories. This is especially true before the Byzantine Iconoclasm of the 8th century.

Christ treading on the beasts is a subject found in Late Antique and Early Medieval art, though it is never common. It is a variant of the "Christ in Triumph" subject of the resurrected Christ, and shows a standing Christ with his feet on animals, often holding a cross-staff which may have a spear-head at the bottom of its shaft, or a staff or spear with a cross-motif on a pennon. Some art historians argue that the subject exists in an even rarer pacific form as "Christ recognised by the beasts".

The Hetoimasia, Etimasia, prepared throne, Preparation of the Throne, ready throne or Throne of the Second Coming is the Christian version of the symbolic subject of the empty throne found in the art of the ancient world, whose meaning has changed over the centuries. In Ancient Greece, it represented Zeus, chief of the gods, and in early Buddhist art it represented the Buddha. In Early Christian art and Early Medieval art, it is found in both the East and Western churches, and represents either Christ, or sometimes God the Father as part of the Trinity. In the Middle Byzantine period, from about 1000, it came to represent more specifically the throne prepared for the Second Coming of Christ, a meaning it has retained in Eastern Orthodox art to the present.

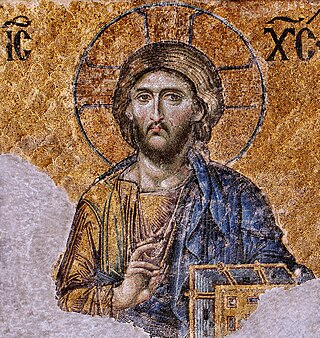

Byzantine mosaics are mosaics produced from the 4th to 15th centuries in and under the influence of the Byzantine Empire. Mosaics were some of the most popular and historically significant art forms produced in the empire, and they are still studied extensively by art historians. Although Byzantine mosaics evolved out of earlier Hellenistic and Roman practices and styles, craftspeople within the Byzantine Empire made important technical advances and developed mosaic art into a unique and powerful form of personal and religious expression that exerted significant influence on Islamic art produced in Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates and the Ottoman Empire.

The Basilica of Santa Maria del Canneto, or Santa Maria Formosa, was a sixth-century Byzantine church. It was erected in Pola under the patronage of Maximianus, bishop of Ravenna. The structure was damaged at the time of the Venetian sack of Pola in 1243, and building material was subsequently taken from the ruins and primarily incorporated into the Marciana Library and the Basilica of Saint Mark in Venice. Of the large, triple-nave church, comparable in splendour to the Euphrasian Basilica in Parenzo, only one of the lateral chapels survives. It constitutes the sole construction in Pola dating to the Byzantine period.