Pax Britannica was the period of relative peace between the great powers. During this time, the British Empire became the global hegemonic power, developed additional informal empire, and adopted the role of a "global policeman".

The Triple Entente describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, the Entente Cordiale of 1904 between France and Britain, and the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907. It formed a powerful counterweight to the Triple Alliance of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Kingdom of Italy. The Triple Entente, unlike the Triple Alliance or the Franco-Russian Alliance itself, was not an alliance of mutual defence.

The Franco-Russian Alliance, also known as the Dual Entente or Russo-French Rapprochement, was an alliance formed by the agreements of 1891–94; it lasted until 1917. The strengthening of the German Empire, the creation of the Triple Alliance of 1882, and the exacerbation of Franco-German and Russo-German tensions at the end of the 1880s led to a common foreign policy and mutual strategic military interests between France and Russia. The development of financial ties between the two countries created the economic prerequisites for the Russo-French Alliance.

The first Anglo-Japanese Alliance was an alliance between Britain and Japan. It was in operation from 1902 to 1922. The original British goal was to prevent Russia from expanding in Manchuria while also preserving the territorial integrity of China and Korea. For the British, it marked the end of a period of "splendid isolation" while allowing for greater focus on protecting India and competing in the Anglo-German naval arms race. The alliance was part of a larger British strategy to reduce imperial overcommitment and recall the Royal Navy to defend Britain. The Japanese, on the other hand, gained international prestige from the alliance and used it as a foundation for their diplomacy for two decades. In 1905, the treaty was redefined in favor of Japan concerning Korea. It was renewed in 1911 for another ten years and replaced by the Four-Power Treaty in 1922.

Relations between France and Germany, or Franco-German relations form a part of the wider politics of Europe. The two countries have a long — and often contentious — relationship stretching back to the Middle Ages. Since 1945, they have largely reconciled, and since the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1958, they are among the founders and leading members of the European Communities and their successor the European Union.

The Reinsurance Treaty was a diplomatic agreement between the German Empire and the Russian Empire that was in effect from 1887 to 1890. Only a handful of top officials in Berlin and St. Petersburg knew of its existence since it was so secret. The treaty played a critical role in German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck's network of alliances and agreements, which aimed to keep the peace in Europe and to maintain Germany's economic, diplomatic and political dominance. It helped keep the peace for both Russia and Germany.

Splendid isolation is a term used to describe the 19th-century British diplomatic practice of avoiding permanent alliances, particularly under the governments of Lord Salisbury between 1885 and 1902. The concept developed as early as 1822, when Britain left the post-1815 Concert of Europe, and continued until the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the 1904 Entente Cordiale with France. As Europe was divided into two power blocs, Britain became aligned with the French Third Republic and the Russian Empire against the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Italy.

The bilateral relations between Germany and the United Kingdom span hundreds of years, and the countries have been aligned since the end of World War II.

The historical ties between France and the United Kingdom, and the countries preceding them, are long and complex, including conquest, wars, and alliances at various points in history. The Roman era saw both areas largely conquered by Rome, whose fortifications largely remain in both countries to this day. The Norman French conquest of England in 1066 decisively shaped English history, as well as the English language; the vocabulary of English is 50% derived from French, including most of the large and complex words.

Russia–United Kingdom relations, also Anglo-Russian relations, are the bilateral relations between Russia and the United Kingdom. Formal ties between the courts started in 1553. Russia and Britain became allies against Napoleon in the early-19th century. They were enemies in the Crimean War of the 1850s, and rivals in the Great Game for control of central Asia in the latter half of the 19th century. They allied again in World Wars I and II, although the Russian Revolution of 1917 strained relations. The two countries were at sword's point during the Cold War (1947–1989). Russia's big business tycoons developed strong ties with London financial institutions in the 1990s after the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. Due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations became very tense after the United Kingdom imposed sanctions against Russia. Russia placed the United Kingdom on a list of "unfriendly countries", along with Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, the United States, European Union members, NATO members, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, Micronesia and Ukraine.

The European balance of power is a tenet in international relations that no single power should be allowed to achieve hegemony over a substantial part of Europe. During much of the Modern Age, the balance was achieved by having a small number of ever-changing alliances contending for power, which culminated in the World Wars of the early 20th century. By 1945, European-led global dominance and rivalry had ended and the doctrine of European balance of power was replaced by a worldwide balance of power involving the United States and the Soviet Union as the modern superpowers.

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), to the end of the First World War and the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920).

The history of French foreign relations covers French diplomacy and foreign relations down to 1981. For the more recent developments, see foreign relations of France.

The history of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom covers English, British, and United Kingdom's foreign policy from about 1500 to 2000. For the current situation since 2000 see foreign relations of the United Kingdom.

The foreign policy of the Russian Empire covers Russian foreign relations from their origins in the policies of the Tsardom of Russia down to the end of the Russian Empire in 1917. Under the system tsarist autocracy, the Emperors/Empresses made all the main decisions in the Russian Empire, so a uniformity of policy and a forcefulness resulted during the long regimes of powerful leaders such as Peter the Great and Catherine the Great. However, several weak tsars also reigned—such as children with a regent in control—and numerous plots and assassinations occurred. With weak rulers or rapid turnovers on the throne, unpredictability and even chaos could result.

International relations (1919–1939) covers the main interactions shaping world history in this era, known as the interwar period, with emphasis on diplomacy and economic relations. The coverage here follows the diplomatic history of World War I and precedes the diplomatic history of World War II. The important stages of interwar diplomacy and international relations included resolutions of wartime issues, such as reparations owed by Germany and boundaries; American involvement in European finances and disarmament projects; the expectations and failures of the League of Nations; the relationships of the new countries to the old; the distrustful relations between the Soviet Union and the capitalist world; peace and disarmament efforts; responses to the Great Depression starting in 1929; the collapse of world trade; the collapse of democratic regimes one by one; the growth of economic autarky; Japanese aggressiveness toward China; fascist diplomacy, including the aggressive moves by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany; the Spanish Civil War; the appeasement of Germany's expansionist moves toward the Rhineland, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, and the last, desperate stages of rearmament as another world war increasingly loomed.

The history of German foreign policy covers diplomatic developments and international history since 1871.

International relations from 1648 to 1814 covers the major interactions of the nations of Europe, as well as the other continents, with emphasis on diplomacy, warfare, migration, and cultural interactions, from the Peace of Westphalia to the Congress of Vienna.

The United Kingdom entered World War I on 4 August 1914, when King George V declared war after the expiry of an ultimatum to the German Empire. The official explanation focused on protecting Belgium as a neutral country; the main reason, however, was to prevent a French defeat that would have left Germany in control of Western Europe. The Liberal Party was in power with prime minister H. H. Asquith and foreign minister Edward Grey leading the way. The Liberal cabinet made the decision, although the party had been strongly anti-war until the last minute. The Conservative Party was pro-war. The Liberals knew that if they split on the war issue, they would lose control of the government to the Conservatives.

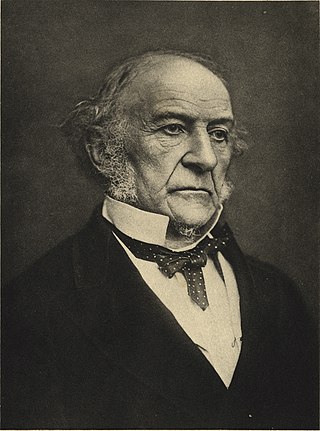

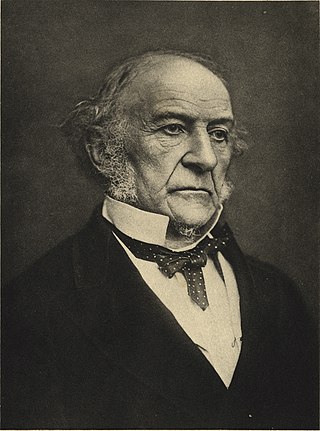

The foreign policy of William Ewart Gladstone focuses primarily on British foreign policy during the four premierships of William Ewart Gladstone. It also considers his positions as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and while leader of the Liberal opposition. He gave strong support to and usually followed the advice of his foreign ministers, Lord Clarendon, who served between 1868 and 1870, Lord Granville, who served between 1870 and 1874, and 1880 and 1885, and Lord Rosebery, who served in 1886 and between 1892 and 1894. Their policies generally sought peace as the highest foreign policy goal, and did not seek expansion of the British Empire in the way that Disraeli's did. His term saw the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1880, the First Boer War of 1880–1881 and outbreak of the war (1881–1899) against the Mahdi in Sudan.