Seville is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Guadalquivir is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The river is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from Seville to the Gulf of Cádiz, but in Roman times it was navigable from Córdoba.

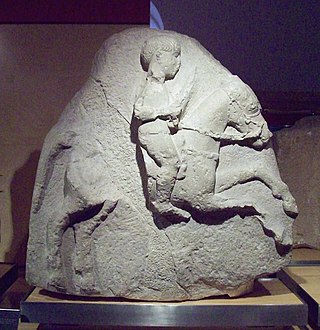

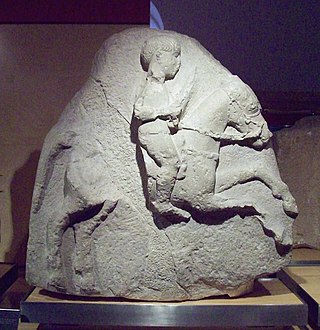

Tartessos is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the southern Iberian Peninsula characterized by its mixture of local Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a writing system, identified as Tartessian, that includes some 97 inscriptions in a Tartessian language.

Huelva is a city in southwestern Spain, the capital of the province of Huelva in the autonomous community of Andalusia. It is between two short rias though has an outlying spur including nature reserve on the Gulf of Cádiz coast. The rias are of the Odiel and Tinto rivers and are good natural harbors. According to the 2010 census, the city had a population of 149,410. Huelva is home to Recreativo de Huelva, the oldest football club in Spain.

A hoard or "wealth deposit" is an archaeological term for a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground, in which case it is sometimes also known as a cache. This would usually be with the intention of later recovery by the hoarder; hoarders sometimes died or were unable to return for other reasons before retrieving the hoard, and these surviving hoards might then be uncovered much later by metal detector hobbyists, members of the public, and archaeologists.

Astarte is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess ʿAṯtart. ʿAṯtart was the Northwest Semitic equivalent of the East Semitic goddess Ishtar.

Xàbia or Jávea is a coastal town and municipality in the comarca of Marina Alta, in the province of Alicante, Valencia, Spain, by the Mediterranean Sea. Situated on the side of the Montgó Massif, behind a wide bay and sheltered between two rocky headlands, the town has become a very popular small seaside resort and market town. Half of its resident population and over two thirds of its annual visitors are foreigners.

Tanit was a Carthaginian goddess. She was the chief deity of Carthage alongside her consort Baal-Hamon.

Álora is a town and municipality in southern Spain in the province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. Located c. 40 km from Málaga, on the right bank of the river Guadalhorce and on the Córdoba-Málaga railway, within the comarca of Valle del Guadalhorce. It is a typical pueblo blanco, a whitewashed village nestled between three rocky spurs topped by the ruins of the castle.

Antequera is a city and municipality in the Comarca de Antequera, province of Málaga, part of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia. It is known as "the heart of Andalusia" because of its central location among Málaga, Granada, Córdoba, and Seville. The Antequera Dolmens Site is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Archaeology Museum of Catalonia is an archaeological museum with five venues that exposes the most important archaeological collection of Catalonia, focusing on prehistoric times and ancient history. The museum was originally founded in 1932 by the Republican Government of Catalonia. The modern institution was created under the Museums of Catalonia Act in 1990 by the Ministry of Culture of the same Government.

Marchena is a town in the Province of Seville in Andalusia, Spain. From ancient times to the present, Marchena has come under the rule of various powers. Marchena is a service center for its surrounding agricultural lands of olive orchards and fields of cereal crops. It is also a center for the processing of olives and other primary products. Marchena is a town of historic and cultural heritage. Attractions include the Church of San Juan Bautista within the Moorish town walls and the Arco de la Rosa. The town is associated with the folkloric tradition of Flamenco. It is the birthplace of artists including Pepe Marchena and Melchor de Marchena, guitarist.

The Treasure of Villena is one of the greatest hoard finds of gold of the European Bronze Age. It comprises 59 objects made of gold, silver, iron and amber with a total weight of almost 10 kilograms, 9 of them of 23.5 karat gold. This makes it the most important find of prehistoric gold in the Iberian Peninsula and second in Europe, just behind that from the Royal Graves in Mycenae, Greece.

The Archeological Museum of Seville is a museum in Seville, southern Spain, housed in the Pabellón del Renacimiento, one of the pavilions designed by the architect Aníbal González. These pavilions at the Plaza de España were created for the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929.

Cancho Roano is an archaeological site located in the municipality of Zalamea de la Serena, in the province of Badajoz, Spain. It is located three miles from Zalamea de la Serena in the direction of Quintana de la Serena Quintana, in a small valley along the stream Cagancha.

The history of Carmona begins at one of the oldest urban sites in Europe, with nearly five thousand years of continuous occupation on a plateau rising above the vega (plain) of the River Corbones in Andalusia, Spain. The city of Carmona lies thirty kilometres from Seville on the highest elevation of the sloping terrain of the Los Alcores escarpment, about 250 metres above sea level. Since the first appearance of complex agricultural societies in the Guadalquivir valley at the beginning of the Neolithic period, various civilizations have had an historical presence in the region. All the different cultures, peoples, and political entities that developed there have left their mark on the ethnographic mosaic of present-day Carmona. Its historical significance is explained by the advantages of its location. The easily defended plateau on which the city sits, and the fertility of the land around it, made the site an important population center. The town's strategic position overlooking the vega was a natural stronghold, allowing it to control the trails leading to the central plateau of the Guadalquivir valley, and thus access to its resources.

Myriam Seco Álvarez is a Spanish archaeologist and Egyptologist. A distinguished authority in those fields, the author of several reference books, and responsible for excavations in the Middle East and Egypt, she has launched and directed important archaeological projects, including the excavation and restoration of the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Thutmose III. The so-called "Spanish Indiana Jones", she has had a prolific professional career and a broad international presence.

Umm Al Amad, or Umm el 'Amed or al Auamid or el-Awamid, is an Hellenistic period archaeological site near the town of Naqoura in Lebanon. It was discovered by Europeans in the 1770s, and was excavated in 1861. It is one of the most excavated archaeological sites in the Phoenician heartland.

Baalshillem I was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He was succeeded by his son Abdamun to the throne of Sidon.

The geostrategic position of Andalusia at the southernmost tip of Europe, between Europe and Africa, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, as well as its mineral and agricultural riches and its large surface area of 87 268 km², formed a combination of factors that made Andalusia a focus of attraction for other civilizations since the beginning of the Metal Age.