The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

Phoenician is an extinct Canaanite Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre and Sidon. Extensive Tyro-Sidonian trade and commercial dominance led to Phoenician becoming a lingua franca of the maritime Mediterranean during the Iron Age. The Phoenician alphabet spread to Greece during this period, where it became the source of all modern European scripts.

The Moabite language, also known as the Moabite dialect, is an extinct sub-language or dialect of the Canaanite languages, themselves a branch of Northwest Semitic languages, formerly spoken in the region described in the Bible as Moab in the early 1st millennium BC.

Edomite was a Northwest Semitic Canaanite language, very similar to Biblical Hebrew, Ekronite, Ammonite, Phoenician, Amorite and Sutean, spoken by the Edomites in southwestern Jordan and parts of Israel in the 2nd and 1st millennium BCE. It is extinct and known only from an extremely small corpus, attested in a scant number of impression seals, ostraca, and a single late 7th or early 6th century BCE letter, discovered in Horvat Uza.

The Punic language, also called Phoenicio-Punic or Carthaginian, is an extinct variety of the Phoenician language, a Canaanite language of the Northwest Semitic branch of the Semitic languages. An offshoot of the Phoenician language of coastal West Asia, it was principally spoken on the Mediterranean coast of Northwest Africa, the Iberian peninsula and several Mediterranean islands, such as Malta, Sicily, and Sardinia by the Punic people, or western Phoenicians, throughout classical antiquity, from the 8th century BC to the 6th century AD.

The Canaanite languages, sometimes referred to as Canaanite dialects, are one of three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Amorite. These closely related languages originate in the Levant and Mesopotamia, and were spoken by the ancient Semitic-speaking peoples of an area encompassing what is today Israel, Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, as well as some areas of southwestern Turkey (Anatolia), western and southern Iraq (Mesopotamia) and the northwestern corner of Saudi Arabia.

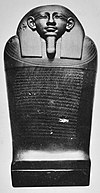

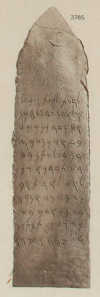

The sarcophagus ofEshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis southeast of the city of Sidon, in modern-day Lebanon, that contained the body of Eshmunazar II, Phoenician King of Sidon. One of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's father King Tabnit and to a woman, possibly Eshmunazar's mother Queen Amoashtart, it was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head. The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

Proto-Canaanite is the name given to

The Paleo-Hebrew script, also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in inscriptions of Canaanite languages from the region of Southern Canaan, also known as biblical Israel and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Hebrew Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script, as the Talmud stated that the Hebrew ancient script was still used by the Samaritans. The Talmud described it as the "Libona'a script", translated by some as "Lebanon script". Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable". The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

The Philistine language is the extinct language of the Philistines. Very little is known about the language, of which a handful of words survived as cultural loanwords in Biblical Hebrew, describing specifically Philistine institutions, like the seranim, the "lords" of the Philistine five cities, or the ’argáz receptacle, which occurs in 1 Samuel 6 and nowhere else, or the title padî.

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze Age. The oldest coherent texts are in Ugaritic, dating to the Late Bronze Age, which by the time of the Bronze Age collapse are joined by Old Aramaic, and by the Iron Age by Sutean and the Canaanite languages.

Old Aramaic refers to the earliest stage of the Aramaic language, known from the Aramaic inscriptions discovered since the 19th century.

The Deir 'Alla Plaster Inscription, known as KAI 312, is a famous inscription discovered during a 1967 excavation in Deir 'Alla, Jordan. It is currently at the Jordan Archaeological Museum. It is written in a peculiar Northwest Semitic dialect, and has provoked much debate among scholars and had a strong impact on the study of Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions.

Samalian was a Semitic language spoken and first attested in Samʼal.

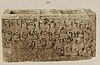

Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften, or KAI, is the standard source for the original text of Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions not contained in the Hebrew Bible.

Jo Ann Hackett is an American scholar of the Hebrew Bible and of Biblical Hebrew and other ancient Northwest Semitic languages such as Phoenician, Punic, and Aramaic.

The Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum is a collection of ancient inscriptions in Semitic languages produced since the end of 2nd millennium BC until the rise of Islam. It was published in Latin. In a note recovered after his death, Ernest Renan stated that: "Of all I have done, it is the Corpus I like the most."

Julius Euting was a German Orientalist.

Scripturae Linguaeque Phoeniciae, also known as Phoeniciae Monumenta was an important study of the Phoenician language by German scholar Wilhelm Gesenius. It was written in three volumes, combined in later editions. It was described by Reinhard Lehmann as "a historical milestone of Phoenician epigraphy".

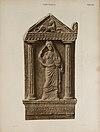

Sakkun was a Phoenician god. He is known chiefly from theophoric names such as Sanchuniathon and Gisgo. As for 1940, his earliest appearance in epigraphical evidence is from the 5th century BC.