Gnosticism is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasised personal spiritual knowledge (gnosis) above the orthodox teachings, traditions, and authority of religious institutions. Viewing material existence as flawed or evil, Gnostic cosmogony generally presents a distinction between a supreme, hidden God and a malevolent lesser divinity who is responsible for creating the material universe. Gnostics considered the principal element of salvation to be direct knowledge of the supreme divinity in the form of mystical or esoteric insight. Many Gnostic texts deal not in concepts of sin and repentance, but with illusion and enlightenment.

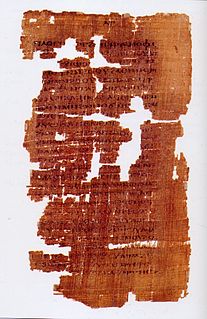

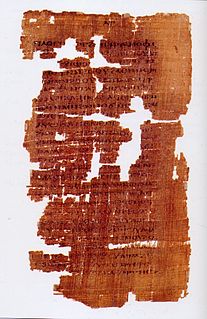

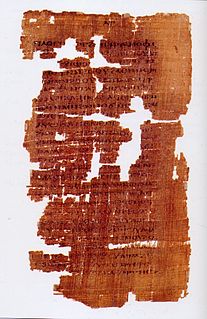

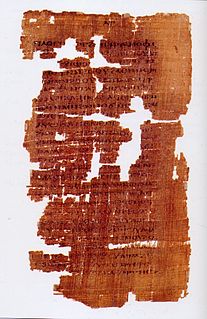

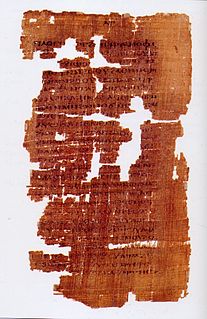

The Gospel of Thomas is an extra-canonical sayings gospel. It was discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in December 1945 among a group of books known as the Nag Hammadi library. Scholars speculate that the works were buried in response to a letter from Bishop Athanasius declaring a strict canon of Christian scripture. Scholars have proposed dates of composition as early as AD 200 and as late as AD 250. Since its discovery, many scholars have seen it as evidence in support of the existence of a "Q source," which might have been very similar in its form as a collection of sayings of Jesus without any accounts of his deeds or his life and death, referred to as a sayings gospel.

The Nag Hammadi library is a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945.

Valentinus was the best known and, for a time, most successful early Christian Gnostic theologian. He founded his school in Rome. According to Tertullian, Valentinus was a candidate for bishop but started his own group when another was chosen.

The Gospel of Philip is a non-canonical Gnostic Gospel dated to around the 3rd century but lost in medieval times until rediscovered by accident, buried with other texts near Nag Hammadi in Egypt, in 1945.

The New Testament apocrypha are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.

Until the discovery of Gnostic works among the hidden cache at Nag Hammadi, few authentic Gnostic works survived. One has been the "Letter to Flora" from a Valentinian teacher, Ptolemy— who is also known from the writings of Irenaeus— to a woman named Flora. The letter itself is only known by its full inclusion in Epiphanius's Panarion, an unsympathetic text which condemns its theology as heretical.

The Letter of Peter to Philip is a Gnostic Christian epistle found in the Nag Hammadi Library in Egypt. It was dated to be written around late 2nd century to early 3rd century CE and focuses on a post-crucifixion appearance and teachings of Jesus Christ to the apostles on the Mount of Olives, or Mount Olivet.

The Apocryphon of James, also known by the translation of its title – the Secret Book of James, is a pseudonymous text amongst the New Testament apocrypha. It describes the secret teachings of Jesus to Peter and James, given after the Resurrection but before the Ascension.

The Sethians were one of the main currents of Gnosticism during the 2nd and 3rd century CE, along with Valentinianism and Basilideanism. According to John D. Turner, it originated in the 2nd century CE as a fusion of two distinct Hellenistic Judaic philosophies and was influenced by Christianity and Middle Platonism. However, the exact origin of Sethianism is not properly understood.

The Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter is a text found amongst the Nag Hammadi library, and part of the New Testament apocrypha. Like the vast majority of texts in the Nag Hammadi collection, it is heavily Gnostic. It was probably written around 100-200 AD. Since the only known copy is written in Coptic, it is also known as the Coptic Apocalypse of Peter.

The Gospel of Truth is one of the Gnostic texts from the New Testament apocrypha found in the Nag Hammadi codices ("NHC"). It exists in two Coptic translations, a Subakhmimic rendition surviving almost in full in the first Nag Hammadi codex and a Sahidic in fragments in the twelfth codex.

The Epistle of the Apostles is a work of New Testament apocrypha. Despite its name, it is more a gospel or an apocalypse than an epistle. The work takes the form of an open letter purportedly from the remaining eleven apostles describing key events of the life of Jesus, followed by a dialogue between the resurrected Jesus and the apostles where Jesus reveals apocalyptic secrets of reality and the future. It is 51 chapters long. The epistle was likely written in the 2nd century CE in Koine Greek, but was lost for many centuries. A partial Coptic language manuscript was discovered in 1895, a more complete Ethiopic language manuscript was published in 1913, and a full Coptic-Ethiopic-German edition was published in 1919.

The term proto-orthodox Christianity or proto-orthodoxy is often erroneously thought to have been coined by New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman, who borrowed it from Bentley Layton, and describes the early Christian movement that was the precursor of Christian orthodoxy. Ehrman argues that this group from the moment it became prominent by the end of the third century, "stifled its opposition, it claimed that its views had always been the majority position and that its rivals were, and always had been, 'heretics', who willfully 'chose' to reject the 'true belief'." In contrast, Larry W. Hurtado argues that proto-orthodox Christianity is rooted in first-century Christianity.

Second Treatise of the Great Seth is an apocryphal Gnostic writing discovered in the Codex VII of the Nag Hammadi codices and dates to around the third century. The author is unknown, and the Seth referenced in the title appears nowhere in the text. Instead Seth is thought to reference the third son of Adam and Eve to whom gnosis was first revealed, according to some gnostics.

The Prayer of the Apostle Paul is a New Testament apocryphal work, the first manuscript from the Jung Codex of the Nag Hammadi Library. Written on the inner flyleaf of the codex, the prayer seems to have been added after the longer tractates had been copied. Although the text, like the rest of the codices, is written in Coptic, the title is written in Greek, which was the original language of the text. The manuscript is missing approximately two lines at the beginning.

Against Heresies, sometimes referred to by its Latin title Adversus Haereses, is a work of Christian theology written in Greek about the year 180 by Irenaeus, the bishop of Lugdunum.

The Tripartite Tractate "was probably written in the early to mid third century." It is a Gnostic work found in the Nag Hammadi library. It is the fifth tractate of the first codex, known as the Jung Codex. It deals primarily with the relationship between the Aeons and the Son. It is divided into three parts, which deal with the determinism of the Father and the free-will of the hypostatized aeons, the creation of humanity, evil, and the fall of Anthropos, and the variety of theologies, the tripartition of humanity, the actions of the Saviour and ascent of the saved into Unity, respectively.

The substitution hypothesis or twin hypothesis states that the sightings of a risen Jesus are explained not by physical resurrection, but by the existence of a different person, a twin or lookalike who could have impersonated Jesus after his death, or died in the place of Jesus on the cross. It is a position held by some Gnostics in the first to third century, as well as some modern Mandaeans and Muslims.

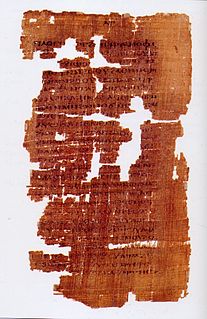

Melchizedek is the first tractate from Codex IX of the Nag Hammadi Library. It is a Gnostic work that features the Biblical figure Melchizedek. The text is fragmentary and highly damaged. The original text was 750 lines; of these, only 19 are complete, and 467 are fragmentary. The remaining 264 lines have been lost from the damage to the text. Like much of Nag Hammadi, the text was likely used by Gnostic Christians in Roman Egypt. It makes reference to Seth, suggesting it may have been used in Sethianism, a school of Gnosticism. The date it was written is unknown; all that can be said is that it was created during the period of early Christianity, presumably at some point during the 3rd century.