The Quasi-War was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States.

The Tariff Act of 1789 was the first major piece of legislation passed in the United States after the ratification of the United States Constitution. It had two purposes: to protect manufacturing industries developing in the nation and to raise revenue for the federal government. It was sponsored by Congressman James Madison, passed by the 1st United States Congress, and signed into law by President George Washington. The act levied a 50¢ per ton duty on goods imported by foreign ships; American-owned vessels were charged 6¢ per ton.

The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War was a conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. The war, contemporary with the War of American Independence (1775–1783), broke out over British and Dutch disagreements on the legality and conduct of Dutch trade with Britain's enemies in that war.

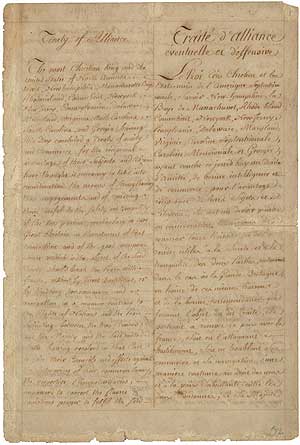

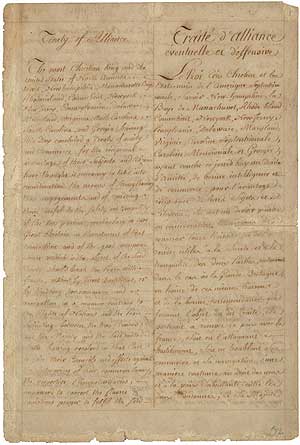

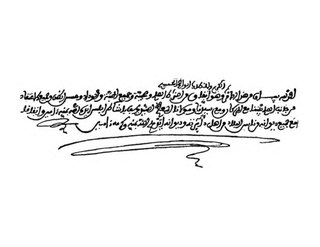

The Treaty of Alliance, also known as the Franco-American Treaty, was a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States formed amid the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. It was signed by delegates of King Louis XVI and the Second Continental Congress in Paris on February 6, 1778, along with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a secret clause providing for the entry of other European allies; together these instruments are sometimes known as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance. The agreements marked the official entry of the United States on the world stage, and formalized French recognition and support of U.S. independence that was to be decisive in America's victory.

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the Barbary Wars, in which the United States and Sweden fought against Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war against Sweden and the United States over disputes regarding tributary payments made by both states in exchange for a cessation of Tripolitatian commerce raiding at sea. United States President Thomas Jefferson refused to pay this tribute. Sweden had been at war with the Tripolitans since 1800.

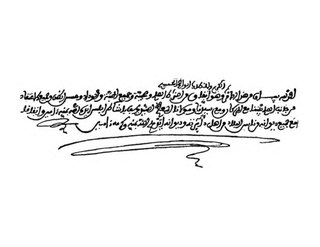

The Treaty of Tripoli was signed in 1796. It was the first treaty between the United States and Tripoli to secure commercial shipping rights and protect American ships in the Mediterranean Sea from local Barbary pirates.

The Continental Navy was the navy of the Thirteen Colonies during the American Revolutionary War. Founded on October 13, 1775, the fleet developed into a relatively substantial force throughout the Revolutionary War, owing partially to the substantial efforts of the Continental Navy's patrons within the Continental Congress. These Congressional Patrons included the likes of John Adams, who served as the Chairman of the Naval Committee until 1776, when Commodore Esek Hopkins received instruction from the Continental Congress to assume command of the force.

The Paris Declaration respecting Maritime Law of 16 April 1856 was an international multilateral treaty agreed to by the warring parties in the Crimean War gathered at the Congress at Paris after the peace treaty of Paris had been signed in March 1856. As an important juridical novelty in international law the treaty for the first time created the possibility for nations that were not involved in the establishment of the agreement and did not sign, to become a party by acceding the declaration afterwards. So did altogether 55 nations, which otherwise would have been impossible in such a short period. This represented a large step in the globalisation of international law.

The Convention of 1800, also known as the Treaty of Mortefontaine, was signed on September 30, 1800, by the United States and France. The difference in name was due to Congressional sensitivity at entering into treaties, due to disputes over the 1778 treaties of Alliance and Commerce between France and the U.S.

The Model Treaty, or the Plan of 1776, was a template for commercial treaties that the United States planned to make with foreign powers during the American Revolution against Great Britain. It was drafted by the Continental Congress to secure economic resources for the war effort, and to serve as an idealistic guide for future relations and treaties between the new American government and other nations. The Model Treaty thus marked the revolution's turning point towards seeking independence, and is subsequently considered a milestone in U.S. foreign relations.

The Committee of Secret Correspondence was a committee formed by the Second Continental Congress and active from 1775 to 1776. The Committee played a large role in attracting French aid and alliance during the American Revolution. In 1777, the Committee of Secret Correspondence was renamed the Committee of Foreign Affairs.

In admiralty law prizes are equipment, vehicles, vessels, and cargo captured during armed conflict. The most common use of prize in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship and her cargo as a prize of war. In the past, the capturing force would commonly be allotted a share of the worth of the captured prize. Nations often granted letters of marque that would entitle private parties to capture enemy property, usually ships. Once the ship was secured on friendly territory, she would be made the subject of a prize case: an in rem proceeding in which the court determined the status of the condemned property and the manner in which the property was to be disposed of.

Conrad Alexandre Gérard de Rayneval, was a French diplomat, born at Masevaux in upper Alsace. He is best known as the first French diplomatic representative to the United States. His brother Joseph Matthias Gérard de Rayneval was also a diplomat.

The First League of Armed Neutrality was an alliance of European naval powers between 1780 and 1783 which was intended to protect neutral shipping against the British Royal Navy's wartime policy of unlimited search of neutral shipping for French contraband during the American Revolutionary War and Anglo-French War. According to one estimate, 1 in 5 merchant vessels were searched by the Royal Navy under this policy. By September 1778, at least 59 ships had been taken prize – 8 Danish, 16 Swedish and 35 Dutch, as well as others from Prussia. Protests were enormous by every side involved.

Diplomacy in the Revolutionary War had an important impact on the Revolution, as the United States evolved an independent foreign policy.

The Franco-American alliance was the 1778 alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which the French provided many supplies for the Americans. The Netherlands and Spain later joined as allies of France; Britain had no European allies. The French alliance was possible once the Americans captured a British invasion army at Saratoga in October 1777, demonstrating the viability of the American cause. The alliance became controversial after 1793 when Britain and Revolutionary France again went to war and the U.S. declared itself neutral. Relations between France and the United States worsened as the latter became closer to Britain in the Jay Treaty of 1795, leading to an undeclared Quasi War. The alliance was defunct by 1794 and formally ended in 1800.

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the United States and Sweden, officially A treaty of Amity and Commerce concluded between His Majesty the King of Sweden and the United States of North America, was a treaty signed on April 3, 1783 in Paris, France between the United States and the Kingdom of Sweden. The treaty officially established commercial relations between these two nations and was signed during the American Revolutionary War.

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the Kingdom of Prussia and the United States of America was a treaty negotiated by Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein, Prussian Prime Minister, and Thomas Jefferson, United States Ambassador to France, and signed by Frederick the Great and George Washington. The treaty officially established commercial relations between the Kingdom of Prussia and the United States of America and was the first one signed by a European power with the United States after the American Revolutionary War. The Kingdom of Prussia became therefore one of the first nations to officially recognize the young American Republic after the Revolution. The first nation to recognize the US was Sweden, who during the Revolution signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce.

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1776 to 1801 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the twenty five years after the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). For the first half of this period, the U.S. f8, U.S. foreign policy was conducted by the presidential administrations of George Washington and John Adams. The inauguration of Thomas Jefferson in 1801 marked the start of the next era of U.S. foreign policy.