Trinity County is a county located in the northwestern portion of the U.S. state of California. Trinity County is rugged, mountainous, heavily forested, and lies along the Trinity River within the Salmon and Klamath Mountains. It is also one of three counties in California with no incorporated cities.

Willow Creek is a census-designated place (CDP) in Humboldt County, California, United States. The population was 1,710 at the 2010 census, down from 1,743 at the 2000 census. Residents of this small mountain town are commonly referred to as "Willow Creekers." The town is located around 30 miles (48 km) from county seat and harbor city Eureka, with the two places vastly differing in climate.

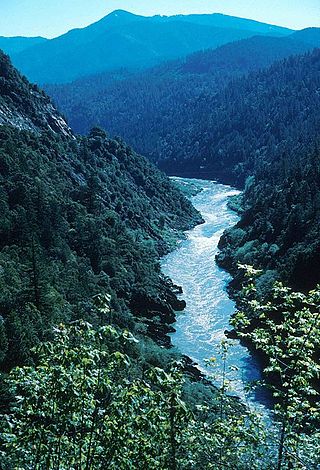

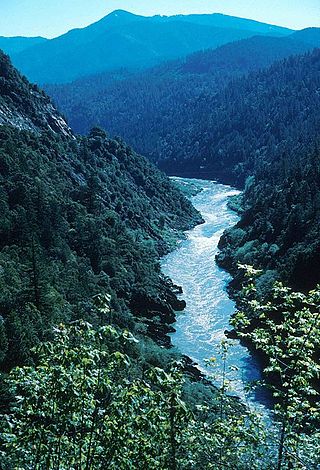

The Klamath River flows 257 miles (414 km) through Oregon and northern California in the United States, emptying into the Pacific Ocean. By average discharge, the Klamath is the second largest river in California after the Sacramento River. It drains an extensive watershed of almost 16,000 square miles (41,000 km2) that stretches from the arid country of south-central Oregon to the temperate rainforest of the Pacific coast. Unlike most rivers, the Klamath begins in the high desert and flows toward the mountains – carving its way through the rugged Cascade Range and Klamath Mountains before reaching the sea. The upper basin, today used for farming and ranching, once contained vast freshwater marshes that provided habitat for abundant wildlife, including millions of migratory birds. Most of the lower basin remains wild, with much of it designated wilderness. The watershed is known for this peculiar geography, and the Klamath has been called "a river upside down" by National Geographic magazine.

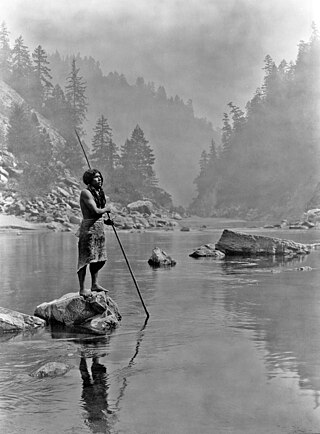

The Trinity River is a major river in northwestern California in the United States and is the principal tributary of the Klamath River. The Trinity flows for 165 miles (266 km) through the Klamath Mountains and Coast Ranges, with a watershed area of nearly 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2) in Trinity and Humboldt Counties. Designated a National Wild and Scenic River, along most of its course the Trinity flows swiftly through tight canyons and mountain meadows.

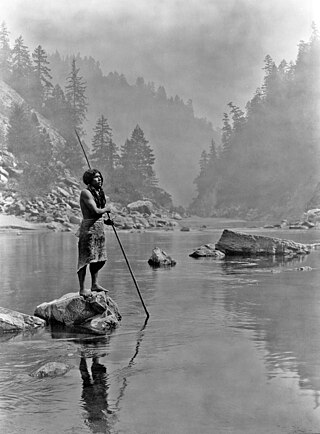

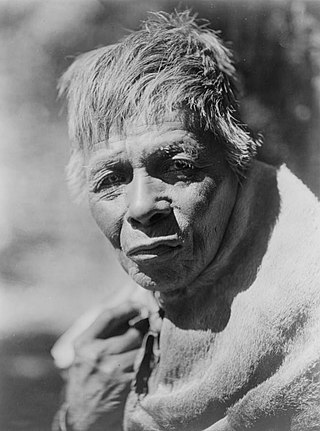

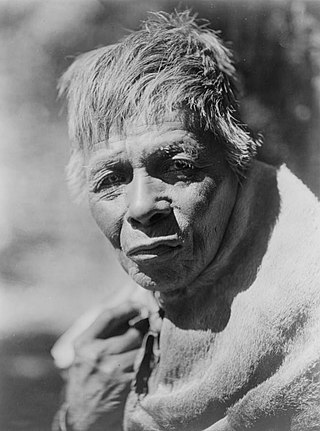

Hupa are a Native American people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group in northwestern California. Their endonym is Natinixwe, also spelled Natinook-wa, meaning "People of the Place Where the Trails Return". The Karuk name was Kishákeevar / Kishakeevra. The majority of the tribe is enrolled in the federally recognized Hoopa Valley Tribe.

Karuk or Karok is the traditional language of the Karuk people in the region surrounding the Klamath River, in Northwestern California. The name ‘Karuk’ is derived from the Karuk word káruk, meaning “upriver”.

Chilula were a Pacific Coast Athabaskan tribe speaking a dialect similar to the Hupa to the east and Whilkut to the south, who inhabited the area on or near Lower Redwood Creek, in Northern California, some 500 to 600 years before contact with Europeans.

Hupa is an Athabaskan language spoken along the lower course of the Trinity River in Northwestern California by the Hoopa Valley Hupa (Na꞉tinixwe) and Tsnungwe/South Fork Hupa (Tse:ningxwe) and, before European contact, by the Chilula and Whilkut peoples, to the west.

Pacific Coast Athabaskan is a geographical and possibly genealogical grouping of the Athabaskan language family.

The Chimariko are an indigenous people of California, who originally lived in a narrow, 20-mile section of canyon on the Trinity River in Trinity County in northwestern California.

Chimariko is an extinct language isolate formerly spoken in northern Trinity County, California, by the inhabitants of several independent communities. While the total area claimed by these communities was remarkably small, Golla (2011:87–89) believes there is evidence that three local dialects were recognized: Trinity River Chimariko, spoken along the Trinity River from the mouth of South Fork at Salyer as far upstream as Big Bar, with a principal village at Burnt Ranch; South Fork Chimariko, spoken around the junction of South Fork and Hayfork Creek, with a principal village at Hyampom; and New River Chimariko, spoken along New River on the southern slopes of the Trinity Alps, with a principal village at Denny.

The Eel River Athabaskans include the Wailaki, Lassik, Nongatl, and Sinkyone (Sinkine) groups of Native Americans that traditionally live in present-day Mendocino, Trinity, and Humboldt counties on or near the Eel River and Van Duzen River of northwestern California.

The Tolowa people or Taa-laa-wa Dee-ni’ are a Native American people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethno-linguistic group. Two rancherias still reside in their traditional territory in northwestern California. Those removed to the Siletz Reservation in Oregon are located there.

The Whilkut also known as "(Upper) Redwood Creek Indians" or "Mad River Indians" were a Pacific Coast Athabaskan tribe speaking a dialect similar to the Hupa to the northeast and Chilula to the north, who inhabited the area on or near the Upper Redwood Creek and along the Mad River except near its mouth, up to Iaqua Butte, and some settlement in Grouse Creek in the Trinity River drainage in Northwestern California, before contact with Europeans.

Burnt Ranch is a census-designated place (CDP) in Trinity County, California. It has a school and a post office. Its ZIP Code is 95527, and it is in area code 530. Its elevation is 1,502 feet (458 m). Its population is 250 as of the 2020 census, down from 281 from the 2010 census.

The New River, , is a 21.4-mile-long (34.4 km) tributary of the Trinity River in northern California. The river was named by miners during the California Gold Rush in the early 1850s. While prospecting west from earlier diggings on the upper Trinity River, they named the river due to it being a "new" place to search for gold.

The South Fork Trinity River is the main tributary of the Trinity River, in the northern part of the U.S. state of California. It is part of the Klamath River drainage basin. It flows generally northwest from its source in the Klamath Mountains, 92 miles (148 km) through Humboldt and Trinity Counties, to join the Trinity near Salyer. The main tributaries are Hayfork Creek and the East Branch South Fork Trinity River. The river has no major dams or diversions, and is designated Wild and Scenic for its entire length.

Copper Creek is a southern tributary of the Klamath River in the U.S. state of California. Arising in the Klamath Mountains, the creek drains a narrow watershed of about 120 square miles (310 km2). Historically, Copper Creek was the site of at least one Hupa Native American village, then was extensively mined for gold in the 1850s. The origin of the name comes from the peach-colored cliffs that line the lower few miles of the canyon.

Camp at Pardee's Ranch was a military post at Pardee's Ranch from 1858 until the end of the Bald Hills War for U.S. Army troops, California State Militia or California State Volunteers.